· 21 min read

“We have given legs, arms and muscle to the Kunming-Montreal Biodiversity Framework”, said COP16 outgoing president Susana Muhammad, over the Resumed Sessions’ final plenary in Rome. Following a forced halt due to a lack of quorum to complete the financing discussion in Cali, the 2024 UN Biodiversity Conference finally reached, on February 28th 2025, a promising agreement on a five-year action plan to unlock necessary funding to safeguard nature. Among the main highlights, it was decided to establish “a permanent arrangement” for a financial mechanism to support developing countries towards achieving biodiversity targets.

In this context, a new platform was launched, called the Cali Fund, to provide a new stream of financing for biodiversity protection by tapping into the value of biological diversity: firms around the globe are using the rich genetic material from biodiversity, for example in the pharmaceutical, chemical and cosmetics industries, and profits thus generated are immense.

While the fund’s operational structure, funding mechanisms, and governance arrangements remain to be determined, it was emphasised that the mobilisation of resources should come from ‘all sources’, which notably includes governments, multilateral development banks and the private sector.

The Cali Fund provides the opportunity for world businesses utilising this genetic wealth to give back to nature on a voluntary basis, by partly funding progress towards the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD)’s objectives and partly supporting indigenous peoples and local communities, including women and youth, recognised as stewards of biological diversity.

As a challenging geopolitical context has recently resulted in a reduction of public funding for nature and climate action, these recent developments not only provide a glimpse of hope for international cooperation but also demonstrate the largely untapped potential of finding innovative ways to mobilise climate and biodiversity finance.

In a time when the WWF 2024 Living Planet Report found a 73% decline in wildlife population since 1970, mainly driven by habitat loss and degradation, recognising the value of natural resources and unveiling their financial potential seems more urgent than ever to reverse this course. And while private finance flows that negatively affect nature (USD 5 trillion) amount to 140 times investments in nature or nature-based solutions, efforts required to shift financial flows away from activities that harm nature toward those that support it represent no small endeavour.

To address this biodiversity finance gap, various financial mechanisms for biodiversity are flourishing around the world, of which the Cali Fund is a recent international example. Eyes are particularly turning towards a few innovative and increasingly recognised mechanisms that can encourage investments in nature and enable new ways of revenue generation: biodiversity credits and de-risking mechanisms. Having witnessed the emerging interest in these solutions in the global discourse, BASE currently explores the potential of biodiversity offsets & credits for accelerating private sector biodiversity finance and the role of blended finance solutions as well as other financing strategies to support biodiversity conservation. In this first article, we reflect on the potential and challenges of biodiversity credits and habitat banking to deliver environmental and social benefits at scale. We clarify key concepts and current developments in the field as part of a broader research effort.

1. Biodiversity offsets & credits – mobilising private capital to nature and local communities:

1.1 Definitions

What is a biodiversity credit?

According to the Biodiversity Credit Alliance, a biodiversity credit “is a certificate that represents a measured and evidence-based unit of positive biodiversity outcome (e.g., restored hectares, increased species numbers) that is durable over a determined period of time and additional to what would have otherwise occurred.” Biodiversity credits represent an asset created through investments in restoration, conservation, and development of biodiversity in a specific landscape. They serve as tradeable units (purchased by companies to meet regulatory requirements or voluntary commitments), functioning as a financial instrument whose value is based on measurable biodiversity improvements, which can include biodiversity gains, reduction in threat, or prevention of anticipated decline.

What types of biodiversity credits are there?

The global landscape of biodiversity credit schemes features both mandatory and voluntary systems. Mandatory biodiversity offsets are typically required by regulatory bodies for projects that cause unavoidable harm to biodiversity. They are designed to compensate for the lost biodiversity by creating or enhancing biodiversity in other locations.

Voluntary biodiversity credits, on the other hand, are a newer market-based approach, where companies invest in projects that actively promote biodiversity conservation and restoration, in response to self-imposed commitments, such as to offset environmental degradation or to simply make a positive contribution to the environment and sustainable development. They are seen as a way to go beyond simply compensating for damage and achieve net-positive impacts on biodiversity.

While compensation schemes make credit purchases mandatory, thereby internalising biodiversity loss as a cost of doing a business activity that yields a negative impact, the voluntary market enables environmental stewardship by companies. Companies can be incentivised to invest in biodiversity restoration or conservation initiatives through the purchase of voluntary biodiversity credits as visible environmental stewardship enhances consumer trust, is appealing to environmentally conscious stakeholders and strengthens company branding.

1.2 Biodiversity offsets & credits for biodiversity finance – Where are we standing?

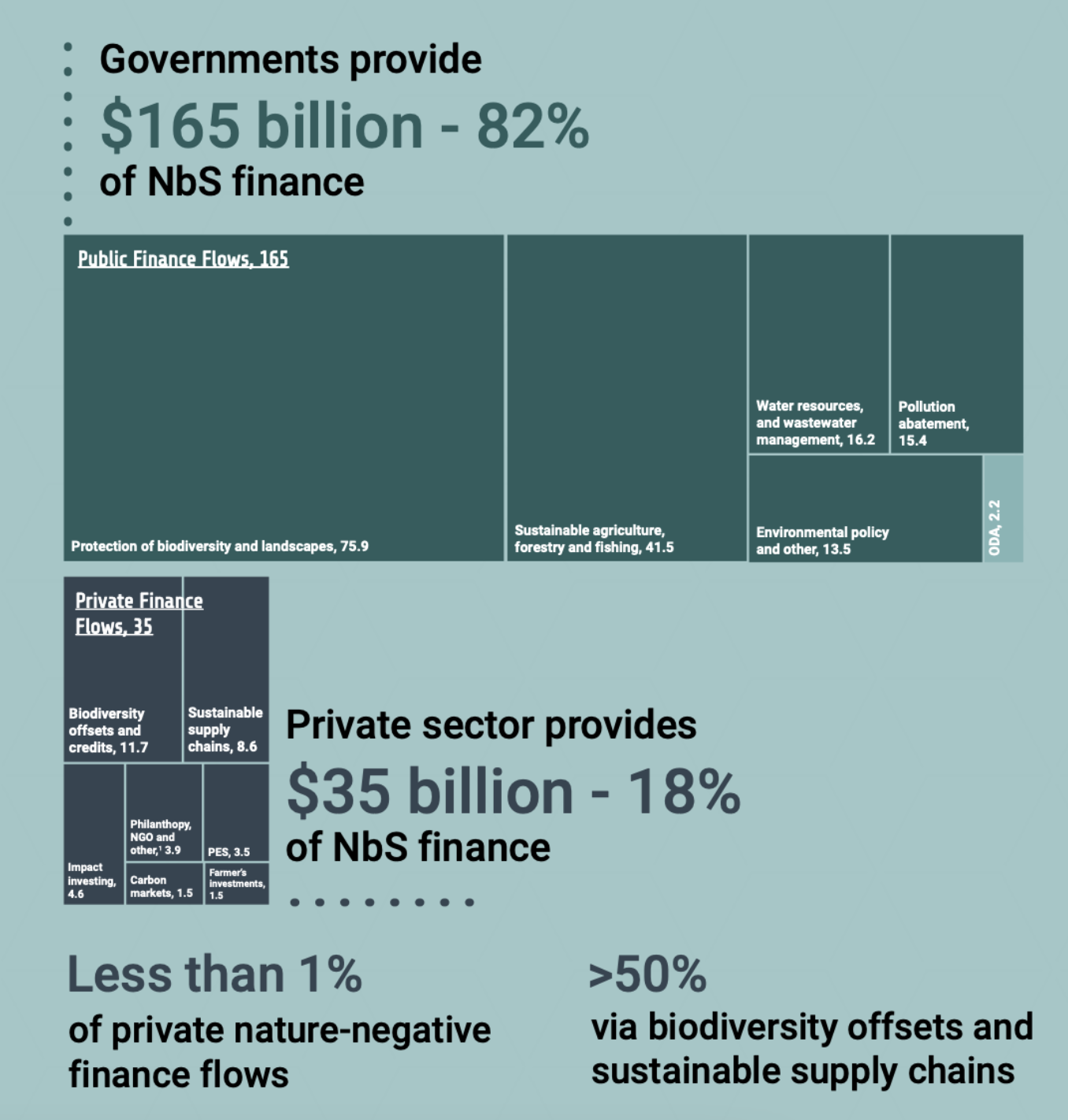

As of 2023 private financial flows to biodiversity amount to USD 35 billion (18 percent) compared to 165 USD billion (82 percent) provided by governments, according to the UN Environment Programme’s (UNEP) latest report on nature finance. As illustrated in the adopted graphic below, biodiversity offsets (via various mechanisms) and credits constitute 11.7 percent of the total amount of private financial flows to Nature-based Solutions (NbS), followed by sustainable supply chains (8.6 percent) and impact investing (4.6 percent). Thus, as of today biodiversity offsets and credits make the largest contribution to private sector biodiversity finance.

Finance Flows for Nature (2023 USD), adopted from UNEP 2023 State of Nature Finance report

The primary market for biodiversity credits resides in the mandatory offset market, driven by regulatory obligations tied to environmental licenses, particularly in sectors like hydrocarbons, mining, and infrastructure, where companies and investors are purchasing credits for ESG commitments, and focus on biodiversity-rich regions like Oceania, Latin America, Africa, and Asia. At least 56 countries – including Australia, Brazil, Canada, China, Colombia, France, Germany, India, Mexico, New Zealand and South Africa – have laws or policies requiring biodiversity offsets or compensatory conservation measures. For instance, in the United Kingdom, the 2024 Biodiversity Net Gain (BNG) policy compels developers to deliver at least a 10 percent net increase in biodiversity for all new projects and, if on‑site improvements prove infeasible, they must purchase statutory biodiversity credits through a government‑operated marketplace. In France, the 2016 Law for the Reconquête de la biodiversité, de la nature et des paysages introduce a framework of “compensation units” to ensure that any environmental damage is balanced by equivalent ecological gains.

While comprehensive global data on the volume of mandatory biodiversity offset markets is limited, national examples illustrate the significant financial flows within such schemes. For instance, the UK’s BNG policy, which became mandatory for major developments in February 2024, is projected to generate an annual market value between GBP 135 million and GBP 274 million. While in Australia, the New South Wales Biodiversity Offset Scheme reported trading 101,894 credits in 2024, amounting to approximately AUD 285 million in value.

According to the Pollination Foundation, between USD 325,000 and USD 1,870,000 worth of voluntary biodiversity credits are estimated to have been sold as of September 2024, representing approximately between 26,000 and 125,000 hectares where positive biodiversity outcomes have been achieved.

Unlike biodiversity offsets, voluntary biodiversity credits are still in an early and experimental phase. While there is growing interest, particularly from the private sector, and the approach is gaining momentum, the market still lacks consistent definitions, standards, and governance.

1.3 How are biodiversity credits generated & how to ensure integrity?

To generate biodiversity credits, a project must demonstrate measurable gains through activities like ecosystem restoration (e.g., reforesting degraded land, wetland rehabilitation), conservation efforts (e.g., protecting endangered habitats, reducing deforestation) or sustainable land management (e.g., agroforestry, regenerative agriculture) over a determined period of time and defined geographical scope.

We elaborate below on some of the key stages of the life cycle of a biodiversity credit project described by the World Economic Forum in: “Biodiversity Credits: A Guide to Identify High-Integrity Projects“

• Feasibility – Initial scoping to assess the viability of a biodiversity credit project, including environmental assessments, legal due diligence, and early stakeholder engagement, particularly with Indigenous Peoples and Local Communities (IPs and LCs), which represent a key pillar of such initiatives

• Project design and financing – Detailed planning of conservation or restoration activities, identification of biodiversity baselines and expected outcomes, and securing appropriate financing

• Registration with a standard – Based on verified outcomes assessed by external auditors, biodiversity credits are issued to the project developer. The project is registered with a recognised biodiversity credit standard or registry, making it eligible to generate credits

• Implementation and monitoring – Execution of planned conservation activities, accompanied by ongoing biodiversity monitoring in line with approved methodologies

• Issuance of Verified Biodiversity Improvements – Upon successful verification, credits are issued by the standard body or registry, representing the biodiversity gains delivered by the project. Issued credits are sold in voluntary markets or, if applicable, compliance markets. Revenues generated are typically allocated towards: continued project operations; payments to landowners or Indigenous Peoples and local communities; building financial reserves for future project maintenance

• Retirement of verified biodiversity improvements – Once purchased and used, credits are retired in an official registry to ensure they are not reused, supporting transparency and integrity.

Whether in the mandatory or voluntary market, an array of integrity principles to assess projects and project developers must be met to ensure investments in biodiversity credits are effective and beneficial. The key principles to safeguard social inclusion and environmental outcomes at every stage of a biodiversity credit project’s life cycle, are illustrated below:

Guardrails in the stages of a project’s life cycle, from Biodiversity Credits: A Guide to Identify High-Integrity Projects

Among the integrity principles presented in the figure above, ensuring additionality, delivering financial benefits to local communities and Indigenous Peoples, and guaranteeing the long-term protection of restored ecosystems are particularly challenging. For this reason, it is worth exploring these principles in more detail.

The additionality principle is especially delicate to address, as it typically requires building a counterfactual scenario assessing the state of biodiversity in the targeted area in the case where no additional activities are undertaken. It is critical to prove that biodiversity credits represent real improvements in ecosystems. If conservation or restoration improvements would have happened regardless of the project, it should not be possible to sell credits for those actions.

In restoration projects, additionality is relatively easier to prove since projects involve clear, measurable interventions (e.g., replanting forests, restoring wetlands) against a low baseline (e.g. degraded land).

For exclusive conservation projects, it can represent a much more difficult task, as protecting existing ecosystems doesn’t always show a measurable “gain”, and projecting a potential loss (e.g. deforestation) represents a very complex task.

To address additionality, some frameworks, like the one created by the indigenous-led company Savimbo in Colombia, avoid counterfactual comparisons altogether, arguing that their complexity provides a space for abuse and excludes indigenous people and local communities. Instead, they assume any conservation effort in a high-threat ecosystem (e.g., IUCN Red List areas or biodiversity hotspots) is inherently additional, as these ecosystems are scientifically documented as being at risk. Since these ecosystems are expected to deteriorate according to publicly available information, any effort to prevent their loss is considered additional. To measure the gains, Savimbo uses a unique technique relying on indicator species. Some species, such as jaguars, can only thrive in healthy ecosystems. Hence, spotting a certain number of an associated selection of flora and fauna species reflects the functionality of the ecosystem. While the company acknowledges that this methodology can be used only for voluntary biodiversity credits – not to certify offsets as it cannot comply with the stricter additionality criteria under the Colombian regulatory framework – it allows for greater inclusivity of Indigenous People.

Making sure the revenues generated by credit sales make their way to Local Communities and that activities benefit them fairly, represents another of the above-mentioned challenging criteria. Local communities and Indigenous peoples often act as primary stewards of the world’s most biodiverse ecosystems, coexisting with and nurturing these landscapes for generations. However, despite their critical role in conservation, they frequently lack financial support and incentives to sustain these efforts. By integrating biodiversity credits into sustainable economic activities such as agroforestry, regenerative agriculture, and community-led conservation, local stakeholders can receive additional income for the positive biodiversity outcomes achieved.

Ensuring benefits to the local population/restoration or conservation stewards is also critical to address the permanence issue. Indeed, unlike traditional short-term grants, biodiversity credits can provide a sustainable revenue stream, reducing economic pressures that often drive environmental degradation and making conservation a viable livelihood option rather than a financial burden.

An increasingly recognised mechanism for generating biodiversity credits is the use of habitat banks. These involved the restoration of degraded or low-quality land to deliver measurable biodiversity gains. What sets habitat banks apart is their strong potential to ensure additionality—a core principle of integrity—by focusing on ecological improvements that would not occur without deliberate intervention. As such, habitat banks offer a promising approach to support biodiversity markets. However, their overall effectiveness and integrity depend on thoughtful design and management. Habitat banks are further elaborated below.

2. The Treasure of Nature: the Concept of Habitat Banking

Habitat banks are parcels of initially low-quality land where nature restoration activities are converted into measurable biodiversity units, or “credits.” These credits can then be traded, either as offsets under mandatory frameworks or within voluntary markets, forming the basis of a market-based mechanism for biodiversity. By aggregating multiple nature restoration projects, habitat banks help create a financial market for biodiversity outcomes.

They can take various forms or arrangements, ranging from individual companies running their own habitat bank projects to markets operated by private entities or public authorities. Rather than being grouped under a unified category, they are more accurately analysed as varied and dynamic policy arrangements.

Habitat Banks have been implemented in several countries around the world, such as the U.S. Australia, Canada, France, Germany, Colombia and the UK. Since its first emergence in the U.S. in the 1980s (back then known as mitigation banking) it has emerged in various forms, such as Australia’s Biodiversity Offset scheme and Canada’s proposed fish habitat bank.

Some examples from around the globe:

Colombia

In 2017, the Colombian government issued regulations for habitat banks, setting requirements for them to be registered and the principles in which they operate. Terrasos stands as a pioneer in Colombia’s biodiversity credit markets, establishing and managing Habitat Banks that integrate conservation with local economic development, including the Meta Habitat Bank, which became Latin America’s first when it was launched in 2016. Since 2017, with support from the IDB Group, Terrasos has successfully registered 13 Habitat Banks, protecting 7,288 hectares across five threatened ecosystems. These projects not only contribute to ecosystem restoration, but also generate employment and economic opportunities for local communities.

In addition to mandatory biodiversity credits, Terrasos’ habitat banks also allow for the allocation of voluntary resources from individuals and businesses by issuing biodiversity credits, driving innovative projects in a growing market. While 1 hectare restored land equivalent to one compliance biodiversity unit sells at USD 10,000, smaller credits made for the voluntary market already sell at USD 25, equivalent to 1 voluntary biodiversity unit and 10m2.

Terrasos involves local communities in long-term biodiversity improvement efforts, requiring a 30-year commitment, which corresponds to the minimum period needed for rainforests to meaningfully regenerate and restore some of the ecosystem services lost due to degradation. However, the exact timeframe can vary based on specific conditions and the particular ecosystem services in question.

With its habitat banking system, Terrasos attempts to shift how environmental offsets are dealt with in Colombia, which used to happen through piecemeal projects lasting for 2-5 years, lacking permanence and sufficient benefits for local communities due to high transaction costs.

England

Since February 2024, developers in England must demonstrate a 10 percent increase in biodiversity to obtain planning permission, a requirement known as Biodiversity Net Gain (BNG). This policy uses a standardised metric to assess a site’s existing biodiversity and guide how it can be enhanced or restored.

To meet BNG obligations, developers can improve biodiversity directly on the development site. If that’s not viable, they may restore ecosystems elsewhere or buy biodiversity credits from habitat banks established by any qualifying land manager or organisation, or from the government as a last resort.

The law is designed to generate long-term funding for biodiversity restoration by incentivising landowners to commit land for ecological recovery for a minimum of 30 years, similar to Colombia’s Terrasos’ model. Eligible restoration actions include planting wildflowers, creating ponds, altering grazing routines, or reducing chemical use on grasslands.

A growing sector now supports the implementation of the BNG framework. Environment Bank, a major credit provider, manages 26 habitat banks across England, while platforms like BNGx help facilitate transactions between developers and landowners.

Australia

Australia’s original biodiversity offset program, known as the BioBanking Scheme, was introduced in New South Wales (NSW) in 2008. It operated as a voluntary market-based system, allowing developers to offset environmental impacts by purchasing biodiversity credits from landholders who committed to conservation or restoration efforts by establishing biodiversity stewardship sites, in other words, habitat banks, under agreements with government authorities. However, the scheme faced challenges, including limited participation and concerns over its effectiveness in achieving conservation goals

In response, the NSW government replaced BioBanking with the mandatory Biodiversity Offsets Scheme (BOS) under the Biodiversity Conservation Act 2016, which commenced on 25 August 2017. The BOS can be considered as a type of habitat banking system, which introduced several improvements with regards to permanence, verification, transparency and accountability. Nevertheless, the BOS has faced criticism regarding its implementation and outcomes. Independent reviews identified issues such as inadequate conservation outcomes and a lack of integrity in the offsetting process. Ongoing reforms aim to further improve the scheme’s effectiveness and integrity.

3. The potential of biodiversity offsets and credits to close the biodiversity finance gap?

While biodiversity offsets and credits make the largest contribution to private sector biodiversity finance, their role in overall biodiversity finance remains limited. The Biodiversity credit markets are small (projected at USD 1–2 billion by 2030) compared to the USD 200+ billion annual biodiversity finance gap.

3.1 Why does their role in biodiversity finance still remain limited?

The role of biodiversity credits in mobilising private sector for biodiversity remains limited, primarily due to several key challenges:

• Lack of Standardisation: There is currently no universally accepted metric or methodology for measuring biodiversity gains: unlike carbon, biodiversity cannot be distilled into a single fungible unit. This led to fragmented standards where credits vary by project, species, region, or methodology, severely limiting comparability and investor confidence. Hence, the trading of credits across regions is almost impossible, which significantly limits investment opportunities.

• Non-fungability of biodiversity: Biodiversity credits are not fungible across regions because biodiversity is highly location-specific. A species or ecosystem in one region cannot simply be replaced or restored elsewhere. Therefore, credits generated in one geography (e.g. a wetland in Colombia) are generally not tradable or recognised in another (e.g. a forest in Indonesia). While cross-regional trading is extremely limited, it’s not always strictly impossible. Some voluntary credit buyers might accept credits from different locations if they meet general criteria (e.g. from the same biome or habitat type). However, this is rare and discouraged in high-integrity markets. This location-specificity fragments the market and limits liquidity, making it hard to scale or attract large institutional investors. Investors can’t easily diversify or hedge across regions the way they can in carbon markets, which dampens interest and capital flows.

• High monitoring costs: High monitoring costs in biodiversity credit projects can hinder scalability by making it expensive to verify and track ecological outcomes over time. These costs often stem from the need for specialised equipment, remote sensing technology, or frequent field assessments to ensure credit validity.

• Market integrity: The lack of rigorous governance and oversight heightens the risk of greenwashing, where companies buy credits without genuinely reducing their biodiversity impacts or harming ecosystems elsewhere. Without strict “like‑for‑like” and “local‑to‑local” principles and independent monitoring, offsets can unintentionally undermine conservation by enabling destruction under the guise of compensation.

• Lower perceived investment potential: Biodiversity projects are often small, localised, and highly context‑specific, making it difficult to aggregate them into investment‑sized portfolios for mainstream financiers. Moreover, expected financial returns are typically low and long‑term, which conflicts with traditional investors’ risk/return profiles and limits scaling beyond niche funding scenarios.

3.2 Is there a clear potential for biodiversity credits to increase private sector biodiversity finance?

The generation of biodiversity credits via habitat banks bears great potential in the sense that habitat banks can generate economies of scale at a local level, reducing monitoring and transaction costs. However, while they can increase returns to investments through their model of operation, high up-front costs with long payback periods may still discourage larger-scale private investment, impeding the growth needed. Additionally, habitat banks must ensure consideration of integrity principles, subject to both the mandatory and voluntary biodiversity credit market.

In a nutshell, voluntary schemes lack unified metrics and risk “greenwashing” if companies use them to claim net-positive status prematurely. Mandatory offsets, while better established, often suffer transparency issues, and a lack of trust impedes market growth without rigorous third-party verification and transparent monitoring. While Mandatory biodiversity offsetting schemes demonstrate an opportunity to channel private finance to nature and local stewards, there are concerns that they do not systemically provide “net biodiversity gains” and that they can provide disincentives to reduce the footprint of economic activities on nature.

There is also debate on whether any offset fully compensates for losses, and concerns about social impacts. Critics illuminate concerns over the actual impact of credits and double counting or poorly designed projects.

Hence, biodiversity offset and credit projects require deep ecological understanding, long-term monitoring, and engagement with Indigenous Peoples and Local Communities (IPLCs).

So, yes — there is potential to scale biodiversity credits up to increase private sector biodiversity finance, but only with strong reforms and integration into broader models:

• Embedding biodiversity credits into hybrid financing models such as debt‑for‑nature swaps or combined carbon‑biodiversity credit frameworks could attract more institutional capital and improve credibility. For instance, debt-for-nature and debt-for-climate swaps, when designed in consultation with Indigenous Peoples and Local Communities (IPLCs) and grounded in national biodiversity strategies, have demonstrated potential for scaling finance in countries burdened by debt while safeguarding biodiversity. When thoughtfully paired with blended finance structures, referring to combining not-for-profit capital (public and philanthropic) with private capital, they help attract more institutional capital and boost credibility.

• Policy support is essential: national frameworks, regulated local markets (rather than global, generalised ones), clear rules on what credits can be claimed, and robust community involvement are needed to build trust and demand

Organisations like the International Advisory Panel on Biodiversity Credits are working to establish high‑integrity guidelines, if these are adopted widely, biodiversity markets could grow significantly, potentially reaching USD 1–2 billion by 2030 (and as much as USD 69 billion by 2050), according to the World Economic Forum.

Conclusions

By attaching a cost to ecological impacts, whether through regulatory obligations or voluntary commitments, nature begins to appear in operational and financial decision-making.

While biodiversity credits are emerging as a promising mechanism to direct private capital towards nature, they are still in an infant stage, with evolving standards, governance gaps, and real concerns around integrity principles, market integrity and scalability.

For the market to grow, several obstacles stand in the way. Habitat banks and biodiversity credit markets offer promising mechanisms to scale private finance for nature, however, their effectiveness hinges on addressing structural and integrity challenges, ranging from high up-front costs, long return horizons, and concerns around ecological integrity and social safeguards. Addressing these barriers requires not just better governance and transparency, but also a strategic shift in how biodiversity finance is structured.

To unlock their full potential and build investor confidence, innovative financing strategies are essential. Emerging research underscores the potential of hybrid finance models, including blended finance and debt-for-nature swaps, to overcome these challenges by crowding in private investment and distributing risk more effectively. Blended finance, in particular, can reduce perceived risks for private investors by using concessional capital or guarantees to improve project bankability, particularly important in nature-based solutions, where revenue streams may be uncertain or delayed. Blended finance structures can also support integrated models such as debt-for-nature swaps or carbon–biodiversity credit frameworks.

To move biodiversity credits from a niche, fragmented mechanism to a credible asset class will require strong policy frameworks, market integrity standards, such as those under development by the International Advisory Panel on Biodiversity Credits, and proactive engagement with local stakeholders to ensure equitable and lasting outcomes.

In this context, blended and hybrid finance strategies are not just optional; they are necessary to build the financial architecture that biodiversity markets need to mature, attract institutional capital, and ultimately deliver the scale of conservation impact the planet urgently requires.

This article is also published on author's blog. illuminem Voices is a democratic space presenting the thoughts and opinions of leading Sustainability & Energy writers, their opinions do not necessarily represent those of illuminem.

Sustainability needs facts, not just promises. illuminem’s Data Hub™ gives you transparent emissions data, corporate climate targets, and performance benchmarks for thousands of companies worldwide.