· 6 min read

The world is always changing, and our decisions matter. 2024 marks the biggest election year in history with over 4.2bn people voting on their future. Change gives us the opportunity to rethink how to deal with underlying problems and enhance our policy response. Companies also realize that survival is not guaranteed by standing still. Awareness and adaptation are essential to individual and corporate survival against a background of environmental change.

In this edition:

- EU elections and environmental policy

- Why incumbent companies need to innovate

- Commodity dependency and the electric-vehicle industry

Under debate: EU elections and environmental policy

The people of the European Union have voted for a new European Parliament. Increased support for right-wing parties in Germany, France, the Netherlands, and Austria as well as a further strengthening of the right in Italy, have raised questions about the direction of future EU environmental policies.

Over the next five years, EU climate measures will depend more on the incoming European Commission, which points to a degree of policy stability. Although the newly-elected European Parliament will get a say on every new green policy, the consensus view is that a rollback in existing policies, i.e. the Green Deal, is unlikely. The problem instead may be that it becomes "more complicated to get new policies off the ground" (as Bas Eickhout, Vice-President of the Greens group in the European Parliament, recently told Reuters). There is likely to be little political appetite, for example, to target the politically-fraught farming sector with new rules (in this context see yesterdays approved Nature Restoration Law, note that the law will be enacted 20 days after being published in the EU Official Journal).

Looking forward, is it likely that the scepticism of much of the European electorate to climate measures will ease? I reckon that three factors will force a reappraisal.

First, it will become increasingly clear that limiting climate change could play a role in addressing politically-contentious issues such as immigration (through reducing the number of people displaced by natural disasters and other ecological threats).[1]

Second, although climate-change measures may increase immediate costs faced by populations (e.g. transport), there will be a growing realisation that the economic damage from unimpeded climate change is likely to be many times larger than the mitigation costs needed to limit global warming to 2.0°C.[2] In other words, sustainability should help boost prosperity, not hinder it.

Third, worsening climate issues are likely to make all of us aware that accepting slower progress on the sustainable transition itself has major risks. The longer we delay change, the more we reduce the number of possible paths we have to limiting temperature gains.[3]

However, complacency would be ill-advised: While there are some indications that electorates are less opposed to environmental measures, and see countermanding them as less of a priority than the political rhetoric often suggests, we need to continue to argue the case for action.

Our view: incumbents still need to innovate

My team and I naturally concern ourselves with the question of how companies successfully navigate change. Long-lasting companies have many different survival strategies. But I think that environmental change will make it increasingly important for them to understand how to manage and innovate in their core competences. The development of the Japanese fishing industry provides a cautionary tale, as demonstrated by Planet Tracker (here). You can go on an expansionary spree, as it did, buying up all elements of the fishing value chain. But if the value chain is itself threatened, in this case through declining fish stocks, then all your efforts will be in vain. It might have been wiser, for example, to have developed alternative sources of fish proteins.

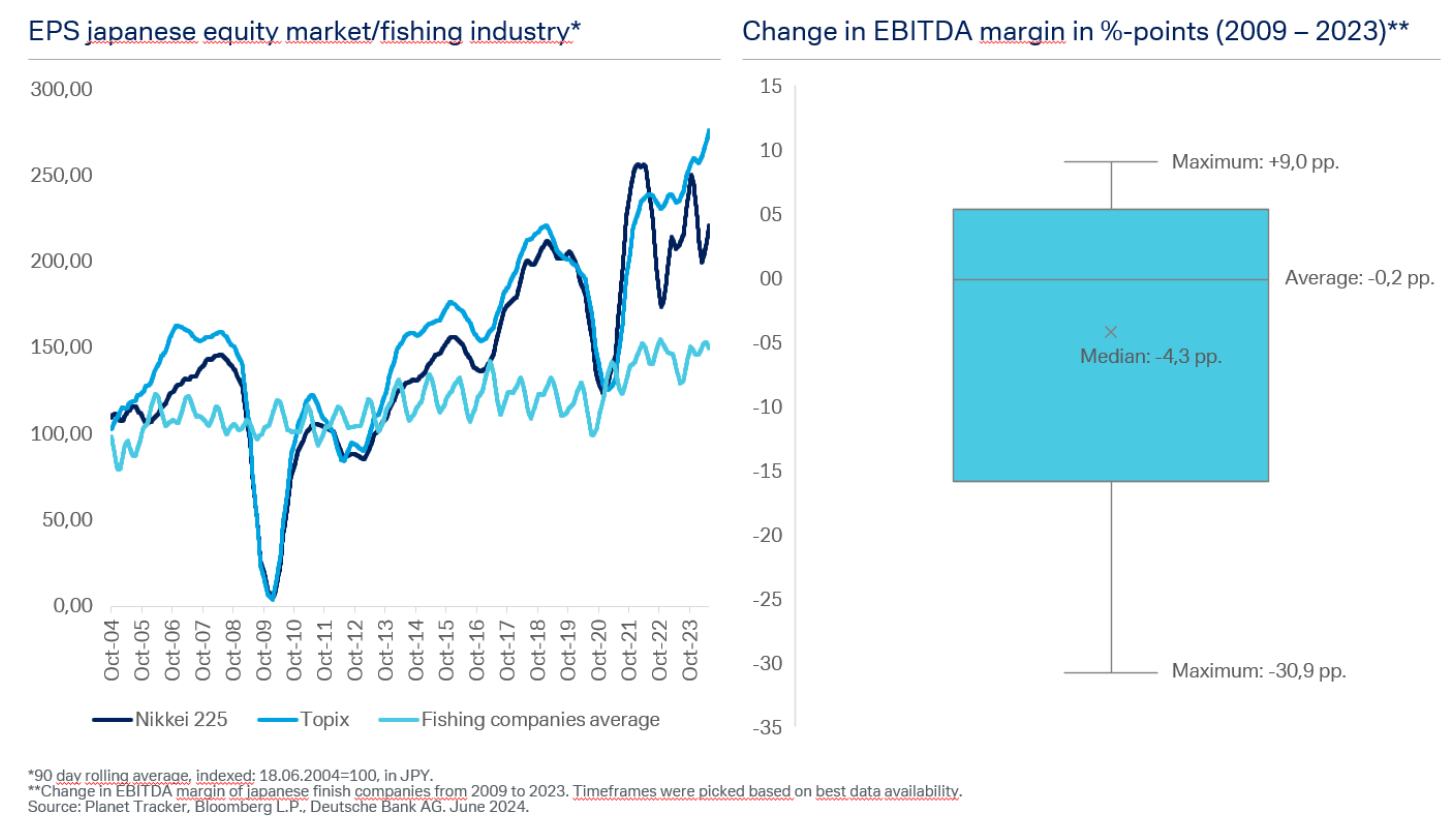

The graph below shows that earnings per share (EPS) of the companies in the fishing sector, on average (excluding four outliers from the total sample of 66 companies), have grown significantly less than the Japanese market, while their EBITDA margins have even decreased on average. Incumbent companies will be key to the sustainable transition, but they need to be innovative too.

Investor perspective: commodity dependency and the EV industry

Lithium companies in the materials sector have had a rough year, with some losing around -60% in share prices YTD. One problem has been a fluctuating price for the mineral, up from ~USD13,500/t at the beginning of the year to a peak of ~USD16,000 /t before falling back to ~USD14,000/t now. Lithium companies’ problems have been one drag on electric vehicle (EV) equity indices.

Lithium prices and availability are particularly important for EV companies, but there appear to be broader concerns around commodity dependency, resource management and future idiosyncratic risk (see our May 5 newsletter).

The dependencies in the automotive industry are extensive. Suppliers often have their own suppliers, who in turn have their own suppliers and so on – a situation that arose from the wave of bankruptcies of many small suppliers in the Great Financial Crisis, after which car manufacturers transferred out the responsibility (and thus the risk) for sourcing their materials. This situation has led to car manufacturers being directly exposed to risks from various areas, such as earthquakes in Japan or trade wars between the U.S. and China. In addition, almost all car manufacturers lack the transparency in their supply chains that analysts might like.

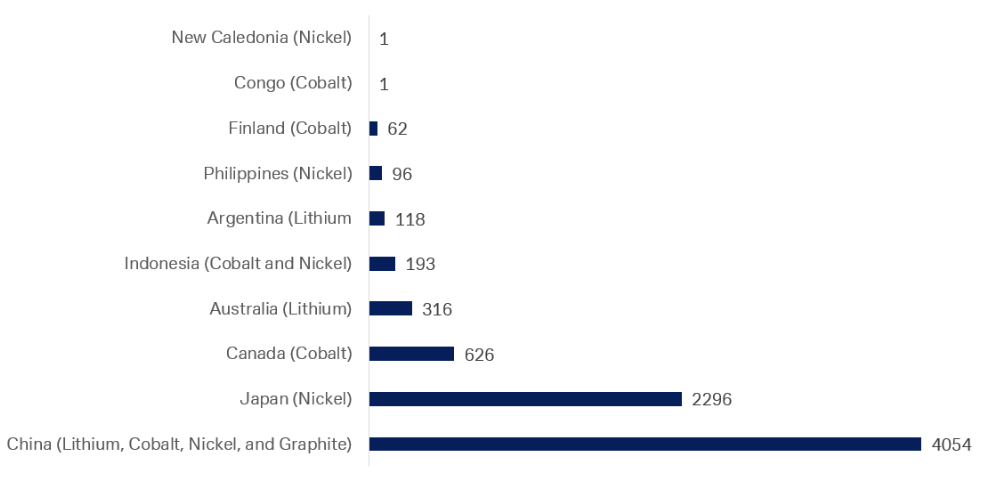

The chart below shows, for just one automotive manufacturer, the number of supplying facilities that it has in each country and the principal commodities taken from this country. This one firm has more than 27,000 supplying facilities all over the world, and not just in the obvious locations.

So how do we evaluate the risks? The U.S. Commerce Department’s Supply Chain Center is now attempting to map them, and I think this will provide many insights. But even operating at the limits of published data, it may be difficult to identify all possible future choke-points. (Who foresaw the impact of COVID-19, for example?)

This article is also published on the author's blog. illuminem Voices is a democratic space presenting the thoughts and opinions of leading Sustainability & Energy writers, their opinions do not necessarily represent those of illuminem.

References

[1] https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/BRIE/2021/698753/EPRS_BRI(2021)698753_EN.pdf