ESG and investment performance: challenges ahead?

· 17 min read

ESG investment has moved in recent years from a niche concern to a central consideration for many investors. After the first two ESG investment phases – of acceptance, then rapid growth – we have now entered a third stage.

This third phase of ESG investment is characterised by a degree of consolidation and reorientation. Investors are becoming increasingly conscious of ESG investment performance – both in terms of financial returns and “real world returns” (i.e. positive effects on the world around us).

Information will be key to this third phase. It has always driven expectations about the two traditional investment dimensions of business and economic development. Information will also now allow us to assess the new third dimension to investment: the limits that a deteriorating natural environment put on how investors and companies can act. This exogenous reality of environmental (E) collapse may also demand a different approach that more endogenous social (S) and governance (G) concerns.

ESG represents a major shift in the social, economic and financial environment, and such regime shifts always raise questions about how investors should assess them. As this report notes, there have been many studies into the effects of ESG on investment returns, but any deductions here still need to be carefully qualified.

As with any investment, the relative performance of ESG investments will of course be dependent on what you are comparing them against and on the time period chosen. One example of the difficulties that investors face in evaluating performance is that ESG investment ratings vary between rating agencies and have also changed over time.

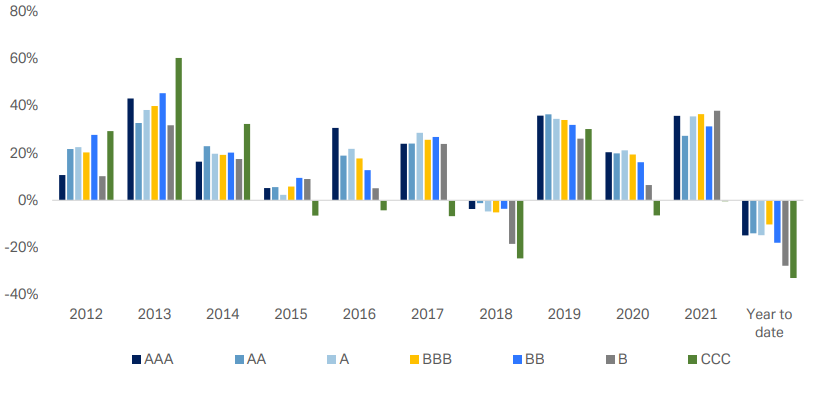

So, for all these reasons, any analysis or presentation of ESG performance (for example, Figure 1) needs to be treated with great care. Similar measurement issues apply to comparisons of ESG assets’ relative volatility.

So why invest on an ESG basis? One initial response might be that it is better to invest in firms that are trying in some way to address the complex environmental and social challenges faced by the world, rather than those firms that appear to be ignoring them.

This altruistic (if perhaps simplistic) response is likely to be supported by practical considerations. We think that companies with strategies to address environmental, social and governance issues are likely, in general, to prove better at navigating an increasingly complex environmental and regulatory environment.

From a portfolio perspective, this ability of firms with ESG strategies to navigate a difficult environment may be valuable. Conversely, investing in firms without a coherent ESG strategy may result in a bumpy ride over the longer term, with less ESGcompliant firms struggling to adapt to regulatory and other developments. If this results in more chopping and changing of investments to replace non-performers, this will have costs for a portfolio – not least because “market timing” mistakes in entering or exiting investments can be expensive.

Clearly, over the short-term, ESG strategies can however underperform. This has been evident in 2022, with many ESG strategies lagging their traditional non-ESG peers. This has been mainly due to the fact that energy and defence-related companies (gainers from the ripple effects of the Russia/Ukraine war) are often excluded from ESG strategies.

ESG investment will continue to evolve. Provision of more standardised data is only a first step and debate about how best to incorporate ESG into investment processes will continue:

ESG is increasingly seen as an additional level of quality assessment on top of traditional economic and financial metrics. Issues such as risk need very careful definition and analysis, for reasons we discuss below. Investors will also continue to look for new ways of measuring the real positive effects of ESG investment on the world around us (e.g. on biodiversity, and via understanding “nature as capital”).

But this is a journey that you need to be part of: ultimately, all investment is ESG investment. Whatever the exact extent of future global temperature rises or biodiversity loss, environmental issues will not go away and social and governance factors will also stay under the microscope. Against this background, it is rational to take non-financial factors into account when assessing investment, and digitalisation makes accessing the information to do this easier. ESG investment has become an effective way of adapting portfolios to this new global reality.

All economic and financial transformations reveal shortcomings in underlying systems. Investors need to be particularly vigilant at times of potential disruption. They need to understand both its financial impact and the implications for the “real world” economic activity.

ESG investing (which can be defined as following the philosophy that investors should consider the impact that their investment decisions will have on the natural world and on society, as well as any financial gains that they might make) represents such a financial transformation and is already changing the way investors and markets assess the investment environment. Investment expectations around ESG have in turn changed as the sector has evolved. (In the discussion below, we focus on individuals’ investments in liquid financial markets, rather than non-liquid investment or institutional activity such as bank financing.)

a) Performance measurement and beliefs

First-phase ESG investment focused on excluding certain stocks or industries, largely because this was the only possible approach given a lack of ESG-related data and definitions. Many investors still follow this approach. One concern, therefore, is how much such exclusions can detract from a portfolio’s performance over the short and long term. (There are also valid questions about what effects such exclusions, e.g. selling individual stocks, will really have.)

During the recent second and third phases of rapid growth in ESG investment, the discussion around ESG performance has become more comprehensive and has expanded to include initial assessments of long-term sustainable performance and portfolio resilience to future environmental (or other) disruption.

Accompanying this, there have been a very large number of studies about the links between ESG and investment performance. As noted above, the results are likely to be heavily dependent on the assets under consideration and the time period surveyed, amongst other factors. Properly identifying causation has also been a particular concern and can have multiple dimensions, perhaps related to the investment process itself – for example, whether the existence of liquid investment flows (which can move out as well as in) can encourage more ESG activity by companies.[1]

In fact, the importance of these studies is probably more in what they do not say, rather than what they do. They do not, overall, point to a negative relationship between ESG investment and performance.

Recognised limitations around single studies have led to various academic meta-studies (i.e. studies of multiple studies). For example, one recent analysis by New York University Stern School of Business[2] looked at 245 studies published between 2016 and 2020, deducing that that 65% showed positive or neutral performance compared to conventional investments with only 13% indicating negative findings. But the results, even of meta studies, can be interpreted in various ways.

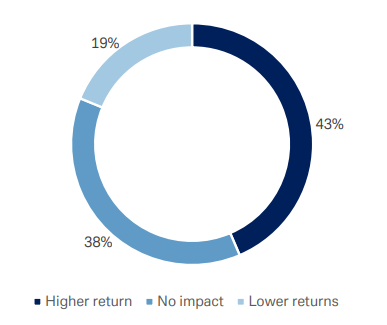

Studies of ESG and investment performance have not come up with definitive answers, but they do appear to have reassured investors that ESG investment will not necessarily always involve compromises around lower returns; as part of this more mature third phase of ESG investment, investors also increasingly want to better assess risks and opportunities. Our own surveys[3] suggest that most investors do not expect ESG to depress returns compared to previous expectations (Figure 2). Our surveys also suggest that a majority of investors are keen that their investment has a positive impact on the world.

b) Achieving consensus on ESG definitions

Investors need however to better understand the relationship between ESG and performance. It is important to understand, for example, whether any positive correlation between ESG and performance is due to other factors – for example, an ESG approach incidentally creating a “quality bias” in the securities selected for investment.

To do this, we first need to address definitional problems.

With “traditional” investment, investors have established definitions of stock and bond market indices and valuation measures, for example. These largely reflect a common understanding of what measures are most important – and have not usually been driven by legal intervention. Reaching this global consensus on how to assess “traditional” asset classes has taken many decades, so progress made so far on ESG metrics and industry disclosure can be seen as relatively rapid.

However, there remain major shortfalls in ESG assessment with only very limited consensus on how to measure ESG for a given asset, firm (or sector) and unresolved conceptual questions about what exactly should be measured.

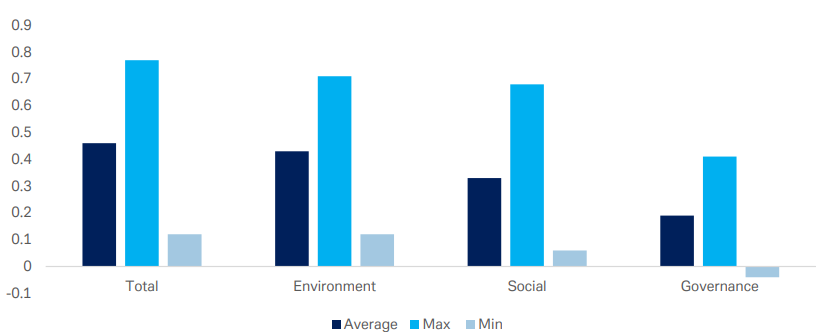

These discrepancies are evident in the variation of ESG ratings between ratings providers (see Figure 3), particularly as regards the “S” (social) and “G” (governance) measures.[4]

It should be noted, too, that while ratings can be a useful overall signal, they may not adequately show underlying negative or positive components.

They are also, by definition, only as good as the data provided, which could unfairly penalise some companies whilst overly supporting others, dependent on regional reporting requirements. (For example, small companies may find the necessary reporting more difficult, due to the cost of obtaining and providing data, and this means that substantial positive contributions by them may not be recognised.) There are also technical issues around rating systems that need attention: for example, as company reporting generally gets better, rating improvements may lead to clusters of firms in the upper percentiles of a rating distribution that make them indistinguishable from each other. Rating methodologies are likely to change to mitigate this fact, but this may in turn result in volatility as measurement systems change. It is worth underlining also that thematic and “real world” impacts are never properly picked up by ratings alone: here the requirement is for more underlying data, or specific information on positive or negative actions (e.g. via taxonomy alignment, or norms violations) as we discuss in the next section.

c) An emphasis on disclosure

Action from regulators to address such shortcomings has been focused on encouraging more disclosure, while developing a suite of ESG classification or definition frameworks. Disclosure plans already go beyond ratings to look, for example, at broader issues around ESG risks, corporate sustainability, environmental impact and human rights/supply chains. Initiatives planned by the Taskforce for Nature-related Financial Disclosures (TNFD), the Taskforce for Climate-related Financial Disclosures (TCFD), the EU’s development of Sustainable Finance Disclosure Regulation (SFDR) and its Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD) all demonstrate broad-based activity on this front.

However, the methodology for underlying assessment is more developed in some areas (e.g. carbon emissions) than others (e.g. ocean finance). There are also some methodological issues that are unresolved globally, e.g. matching the EU taxonomy’s “double materiality” concept (a company must look both at whether an activity is both helping to achieve agreed objectives, and whether it “does no significant harm”) with the existing company focus on financial risks and goals.

Discussions around disclosure and ratings are also taking place in the context of financial sector regulation. For example, the European Securities and Market Authority has recently (June 2022) published the results of a call for evidence on ESG ratings, covering both ESG ratings providers and users. Shortcomings identified by ESG rating users included complex and unclear methodologies, and insufficient granularity of data. Firms covered by ESG ratings also expressed concern about a lack of transparency.

Initiatives to make the data more robust are all regional and it will take time to fully implement a global framework. Without that read-across, it will be difficult for firms to deliver against competing regional standards and disclose comparable material consistently. This could inadvertently lead to difficulties in accessing global sources of finance and supply chains. (Even within the most ESG-enthusiastic region – Europe – there are marked differences in national practices.)

At an asset class level, there has also been an increase in industry body demand for better metrics. The International Capital Market Association has, for example, published new guidance for sustainability-linked bond issuers focused on how to select appropriate metrics. The recently-formed International Sustainability Standards Board (ISSB) proposed standards may also start to gain traction with financial market regulators.

Markets are currently focused on ESG ratings but standardisation here will not solve all the conceptual problems around ESG investment. More consistent ESG ratings will help build a consensus about the relative importance of ESG-specific factors but this consensus is certain to change over time. Ratings are only one issue in building enhanced systems of portfolio management.

a) The different types of risk

Understanding risk will be central to this process of portfolio management. Many different forms of risk exist in ESG investment and investors need to be careful not to confuse them.

From a portfolio perspective, it makes sense to focus first and foremost on financial risk – the downside risk to the value of a company, evident through volatility or measures such as value at risk.

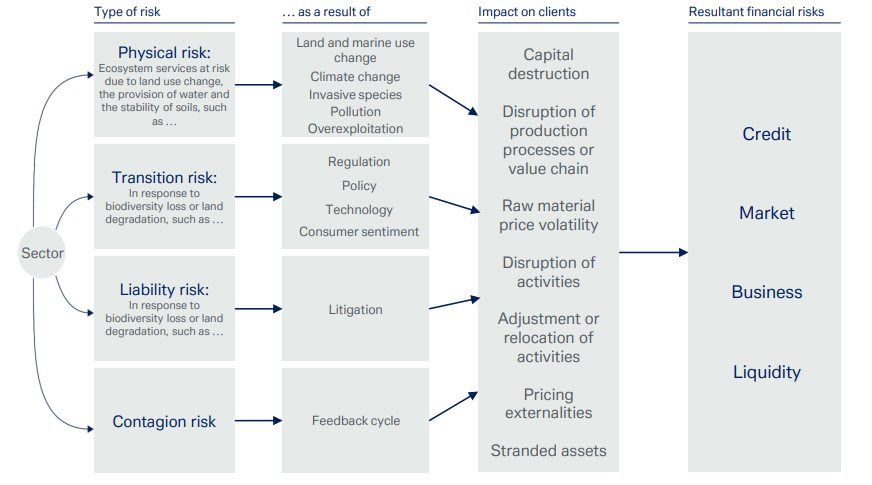

Financial risk is very different from the longer-term business risk faced by organisations. These business risks can be classified in various ways. (Figure 4 shows one common classification into physical, transition, liability and contagion risks.) The study of financial risk is more advanced than that of the other sorts of risk and there is considerable existing academic literature on this area. Some studies have focused on the link between ratings and stock price volatility, looking at the impact of ratings changes as well as overall ratings levels.[5] Others have broadened out to look at the link between ESG ratings and idiosyncratic risk (i.e. price movements not associated with overall market movements).

Several studies point to higher ESG scores being associated with lower level of risk regarding stock price volatility and idiosyncratic risks[6] and (in one study) higher social (S) scores were associated with a reduction of the impact on asset prices from the global financial crisis.[7]

The usual caveats must of course apply around time frames, causality and the ability of past studies to predict the future: the Russia/Ukraine war has reminded us, yet again, that major risk events are often not foreseen and that the knock-on effects can have a major impact on relative investment performance. (Defence and energy sectors, for example, have both gained as a result of the war. Because these two sectors are often excluded from ESG strategies, many have underperformed in recent months.)

Business risks are for the moment less well understood than financial risks but are still important, most immediately in how they are priced into the current price of a security – and over what time periods. A recent study by our investment bank colleagues has suggested that markets may price transition risk as a more immediate threat, and physical risk as a longer-term issue. Equities pricing for climate risks, for example, can often be immediately affected by changes in company-level ESG strategies and macro ESG policy decisions.[8]

A different approach to assessing the markets’ approach to business risk is to consider a company’s weighted average cost of capital (WACC). One key assumption of ESG investment is that better ESG scores will be reflected in a lower WACC (as lenders see less risk of corporate and thus repayment failure). There is already some evidence that a company’s environmental rating will impact its WACC – but the effects will vary across sectors and depend on the level of corporate disclosure.[9]

In the immediate future, investors may continue to approach the problem of financial risk through looking at the apparent relationship between ESG scores and stock price volatility. Other proxy measures (e.g. carbon pricing) may be used to assess business risk. There may also be room for more discussion about the fundamental nature of risk in this new environment – as was started by Keynes and Knight almost a century ago.

b) Measuring “real world returns”

Investors need to consider financial returns and risk, but they will also want to be confident that their ESG investments are making a material improvement to the environment or other desired aspects of the world we live in: this, after all, is the real point of ESG investment and what we refer to as “real world returns”.

The challenge for a portfolio is to assess these “real world returns” in a coherent way. Judging the environmental (or social or governance) impact of an individual investment can be difficult, let alone the optimum combination of them in a portfolio. In a financial system which (rightly or wrongly) must translate complicated “real world” situations into mathematical analysis, this may be particularly difficult.

The highly important issue of biodiversity provides an example of the complexities involved.[10] At least six major approaches assess corporate biodiversity footprints in different ways. However, there may be common themes appearing, for example, the concept of “natural capital” – i.e. seeing the earth’s natural resources as akin to a “capital stock” which we need to manage sustainably. The ENCORE approach (in full: exploring natural capital opportunities, risks and exposure), for example, provides a view of how economic activities might depend on or impact this “natural capital”. Theoretical next steps here, for example, could include rewarding corporates that enhance “natural capital” and penalising those that reduce it: we can see evidence of this approach in the May 2022 agreement by G7 Ministers of Climate, Energy and the Environment to implement the System of Environmental Economic Accounting (SEEA).

Moving from such useful concepts to agreed and standardised measure of investment impact will be difficult – and will of course depend on external factors such improvements in our understanding of environmental relationships and processes. But better measurement here of “real world returns” may turn out to be more important than refining more theoretical ESG ratings structures.

ESG investment is entering a new phase of consolidation and reorientation. With ESG increasingly central to investors’ portfolios, we all need a better understanding of the links between ESG, portfolio returns and the different types of risk.

Consensus on ESG assessment ratings is a necessary next step and should help provide a better guide to firms’ exposure to ESG-related risks. However, this is not the only issue and ESG metrics will continue to evolve in many other areas too – including better assessments of the “real world” impact of ESG investments.

We do not expect a perfect solution to ESG measurement issues. It is also clear that, even with a better assessment system, individual highly ESG-rated stocks may not deliver improved short-term returns or be immune from sharp drawdowns. However, existing studies already suggest that ESG strategies do not need to have a detrimental effect on long-term returns.

At a broader level, we think that the case for ESG investment is nonetheless still compelling and goes beyond the altruistic appeal of investing in companies that want to find solutions to the world’s problems – not just ignore them.

This is because the altruistic case for ESG investment is likely to be supported by practical portfolio management considerations. We think that firms with a coherent ESG strategy are more likely, in general, to able to navigate complex global environmental and social problems ahead. Identifying and holding such firms may also reduce the market timing dangers around portfolio changes.

Ultimately, all investment is ESG investment – portfolios will have to reflect this.

This article is also published by the Deutsche Bank CIO Office . Illuminem Voices is a democratic space presenting the thoughts and opinions of leading Energy & Sustainability writers, their opinions do not necessarily represent those of illuminem.

[1] Aghion, Philippe, Van Reenen, John and Zingales, Luigi. Innovation and Institutional Ownership, American Economic Review 2013. See: https://mitsloan.mit.edu/shared/ods/documents?DocumentID=2566

[2] ESG and Financial Performance: Uncovering the Relationship by Aggregating Evidence from 1,000 Plus Studies Published between 2015 – 2020” of the NYU Stern Center for Sustainable Business and Rockefeller Asset Management (p. 2). See: https://www.stern.nyu.edu/sites/default/files/assets/documents/NYU-RAM_ESG-Paper_2021%20Rev_0.pdf

[3] Deutsche Bank International Private Bank “Biodiversity loss: recognising economic and climate threats” 2021.

[4] Gibson, Rajna and Krueger, Philipp and Schmidt, Peter Steffen, ESG Rating Disagreement and Stock Returns. Swiss Finance Institute Research Paper No. 19-67, European Corporate Governance Institute – Finance Working Paper No. 651/2020, Financial Analyst Journal, Forthcoming, Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3433728 or http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3433728

[5] Giese et al. (2019) ibid.

[6] Sassen, Remmer, Anne-Kathrin Hinze, and Inga Hardeck. "Impact of ESG factors on firm risk in Europe." Journal of business economics 86.8 (2016): 867-904. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s11573-016-0819-3

[7] Bouslah, K., Kryzanowski, L. & M’Zali, B. Social Performance and Firm Risk: Impact of the Financial Crisis. J Bus Ethics 149, 643–669 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-016-3017-x

[8] Deutsche Bank Research, Climate risk pricing in markets, June 2022. https://research.db.com/research/research/Document?rid=051784c8_0a52_4d74_968b_be41b78192aa_604&kid=ESN001& wt_cc1=ind-642076-9405

[9] Deutsche Bank Research, ibid.

[10] Deutsche Bank International Private Bank, Biodiversity: the new playing field for ESG Assessment, March 2022. https://deutschewealth.com/en/our_perspective/cio-specials/biodiversity-new-playing-field-esg-assessment.html

Alex Hong

Energy Transition · Energy

Steven W. Pearce

Adaptation · Mitigation

John Leo Algo

Ethical Governance · Environmental Sustainability

Financial Times

Sustainable Finance · ESG

Sustainability Magazine

Net Zero · ESG

Responsible Investor

AI · Sustainable Finance