Energy for peacebuilding program

Canva Pro

Canva Pro Canva Pro

Canva Pro· 9 min read

The “Energy for Peacebuilding” program aims at bridging efforts towards SDG 7 (Affordable and clean energy) and SDG 16 (Peace, justice, and strong institutions). Specifically, its main goal is to raise access to electricity rates and energy consumption levels in conflict-affected IDA borrowing countries. In order to do so, it proposes a framework where power sector projects are deployed in conjunction with peacebuilding initiatives.

The Program entails two categories of projects with separate but complementary vocations:

Initiatives in this block have the twofold objective of maximizing the positive impact of energy projects in countries or regions where natural resources ownership and management is a contentious matter, likely to trigger local or border conflict if not properly handled; and contributing to longer-term de-escalation of tensions.

The first point focuses on using conflict analysis to ensure benefits and externalities are fairly distributed within communities, with dialogue helping to sustain positive impacts. The second point extends this by combining peacebuilding tools and context-sensitive project implementation to reduce long-term disputes over energy resources.

This scheme has a broader logic, as its main objective is to help create the conditions for sustainable peace in countries or regions that have been affected by internal armed conflicts. In this case, the energy project must be designed as a catalyser for social reconstruction that creates jobs, business, and intergroup cooperation opportunities.

While all types of infrastructure offer these opportunities when employed through a holistic approach, a successfully implemented energy project has the added value of powering local businesses, public services, and households: even though energy alone does not suffice for generating peace or growth, it is in most cases an essential condition for cultivating the social and economic capital needed to disincentivize violence.

The Program allows flexibility in infrastructure and energy sources but requires alignment with key principles. Projects must consider local social, political, and economic factors, ensuring they don't exacerbate conflict, such as avoiding corruption-prone management in sensitive areas. It emphasises community ownership by fostering local participation in decision-making and collaborating with peacebuilding actors. Additionally, the initiative should create local jobs, develop relevant skills, and ensure fair job distribution across groups. Finally, it calls for timely conflict analysis to adjust the project as needed to address evolving issues.

To be eligible for the program, the application must be submitted by the State, and the applicant must be eligible for IDA borrowing. The initiative must also meet the requirements outlined in point (II). For Block B eligibility, a country or region is considered "post-conflict" if it has experienced intrastate or non-state armed conflict, or systematic one-sided violence (resulting in at least 25 civilian deaths in a year) within the past 10 years. Countries can apply no earlier than 3 months after the cessation of hostilities, such as the signing of a peace agreement or a permanent ceasefire with a planned peace process.

The Program prioritises initiatives that include clean energy sources in line with SDG 7, gender-sensitive dialogue and professional opportunities, and youth-led local peacebuilding activities.

Countries that do not figure in the list of eligible beneficiaries for UNPBF financing can apply simultaneously to the UNPBF and the Program.

The application for the Program must contain a context section, followed by a summary of relevant peacebuilding initiatives already in place, and a brief concept note explaining how it pursues access to electricity or energy consumption goals in conjunction with conflict-prevention or post-conflict community-building (in other words, how it aligns with the Program’s Concept), and presenting proposals aligned with the General specifications.

Eventual assisting and implementing partners must be jointly designated by the government and the UN Peacebuilding Commission (UNPBC).

Among the eligible initiatives, the UN Peacebuilding Support Office (evaluating only the peacebuilding aspects) and an energy commission from the UN Development Program (UNDP) assessing the energy project’s feasibility will jointly select a number of initiatives to recommend to the UN Secretary-General (according to available funding) based on the preferential criteria and the feasibility of the energy project. The possible outcomes of the selection are: acceptance (with eventual recommendations from the two bodies), conditional acceptance (behind adoption of recommended measures), rejection.

All initiatives are co-funded through UN PBF grants and eventual partners’ grants or concessional lending. The UN PBC can decide to involve any stakeholder it deems appropriate, as long as they comply with the principle of ‘Timeliness and Sustained Engagement’ in peacebuilding.

This section presents two proposals for pilot projects, each per category. For category (A) the applicant is the government of Guinea-Bissau, while the project proposed under category (B) targets the Tigray region in Ethiopia.

In the first case, a UN-funded peacebuilding project for natural resources management is already underway.

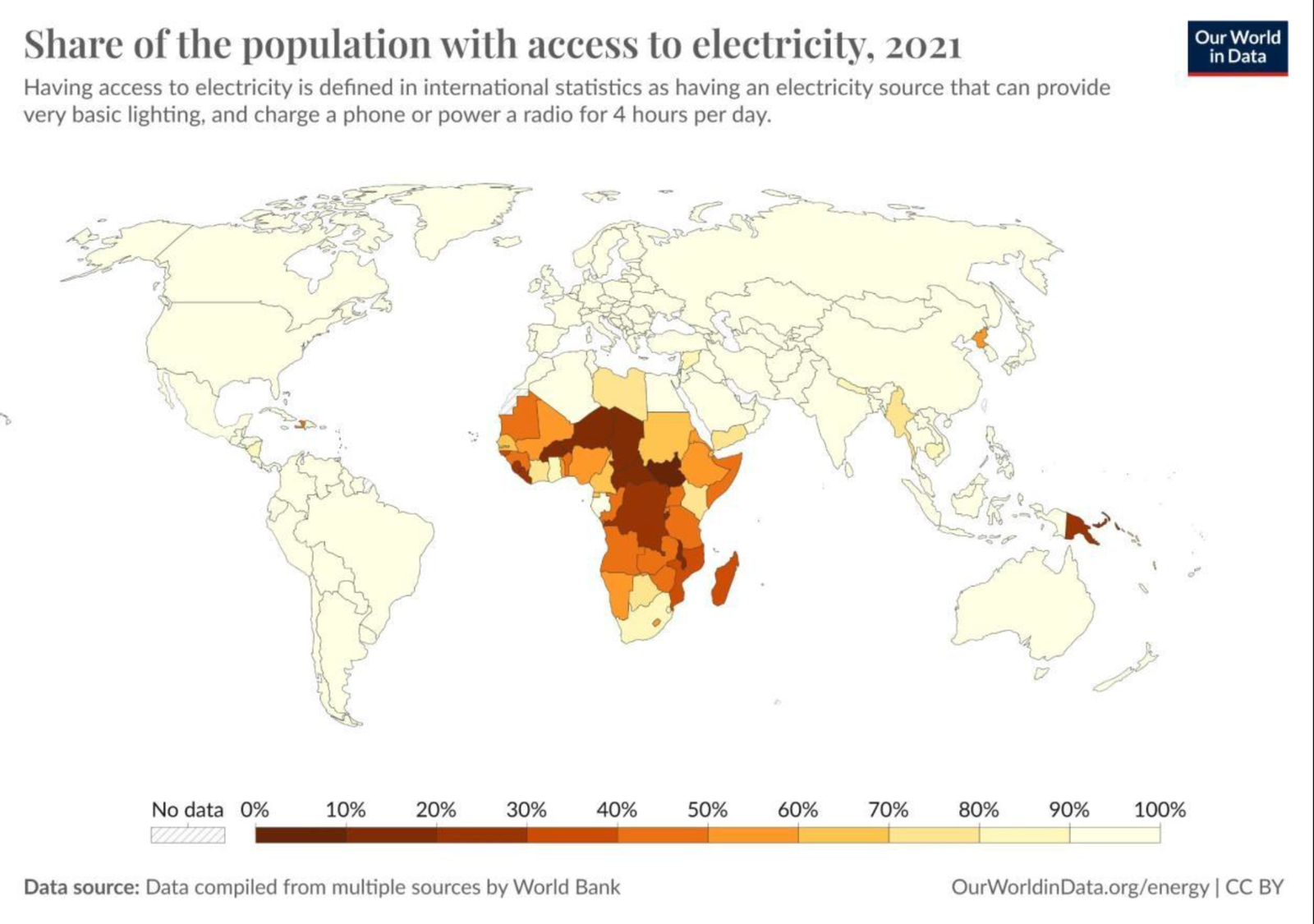

Context: In Guinea-Bissau, only 37.4% of the population has access to electricity, with even lower rates in rural areas (15.8%). The country faces energy imbalances due to insufficient generation capacity and outdated distribution networks. Although Guinea-Bissau has untapped hydropower potential, water resource management issues have fueled intercommunal conflict. In November 2023, the OMVG validated a feasibility study for a run-of-river hydropower station on the Corubal River, set to provide 20-54 MW of power, covering two-thirds of the country's energy demand. However, local agricultural and pastoral communities heavily rely on water from the Koliba-Corubal Basin, which has led to conflicts over water access. The government proposes integrating the project into the "Energy for Peacebuilding" program to balance energy access with conflict prevention.

Existing relevant peacebuilding initiatives: To address the risk of water conflict outbreak, the UNPBF-funded ‘PBF/IRF-546: Peaceful Natural Resources Management in the Koliba-Corubal Basin’ was launched in 2024, with the goal of supporting communities in developing gender-sensitive and sustainable water planning and using instruments for increasing household self-sufficiency. Until now, this initiative has created listening clubs for promoting youth and women’s role in water management in 20 provinces, as well as updating water (access) point inventory in downstream Koliba-Corubal Basin (Gabù, Tombali) in a conflict-sensitive way.

Concept note: This initiative aims to improve electricity access in the Koliba-Corubal Basin through the Saltinho hydropower project while preventing water-related conflicts. The project could trigger disputes by limiting water access or unevenly distributing benefits. To mitigate this, environmental flow releases and an Integrated Water Resource Management (IWRM) strategy will address seasonal flow variability and consider local agricultural and pastoral needs. Conflict-sensitive distribution networks will ensure equitable benefits across communities. Community dialogue and workshops will inform the IWRM strategy, while a youth-focused professional development program will build local capacity in distribution network management. These measures aim to prevent conflict and foster long-term social and economic benefits

Context: Between 2020 and 2022, the Tigray region underwent a brutal civil war that, other than producing around 600.000 casualties, caused severe damage to infrastructure. The conflict ended with a peace agreement between the Ethiopian federal government and the TPLF (Tigray People’s Liberation Front) in November 2022, which among 15 provisions established the ‘restoration of basic, essential (public) services as soon as possible’ in Tigray. One month later, the region was reconnected to the national grid. However, infrastructure reconstruction suffers from underfunding. In Ethiopia, 55% of the population has access to electricity, presenting a big gap between the urban (94%) and rural areas (43%). Although no official data on Tigray is available, it is plausible to assume that in light of the recent conflict, access to electricity in rural areas is not higher than the national average.

The Tigray region is governed by the Interim Regional Administration, with the TPLF holding 51% of power, leading to internal struggles that threaten stability. Political violence in the neighbouring Amhara region further worsens Tigray’s security, making community rebuilding and personal development crucial to preventing violence.

Existing relevant peacebuilding initiatives: Ethiopia does not figure in the list of countries eligible for the UNPBF, and no Immediate Response Facility initiatives are active.

In Tigray, some local and international NGOs are pursuing projects mostly focused on local governance and humanitarian assistance. An initiative by VNG International targets the implementation of community-driven infrastructure rebuilding programs, but not related to the energy sector.

Concept note: This initiative plans to deploy decentralised solar PV systems in rural Tigray, starting with Mychew Tabia Smret, an area suited for solar energy and near the Amhara region. The solar PV systems will be integrated with agriculture, primarily wheat cultivation, using agrivoltaic methods. Local workers, especially former fighters, will be prioritised for installation after training, fostering community ownership and future employment opportunities. Over three years, the community will take full management control, supported by gender-balanced and youth-inclusive teams. A reconciliation dialogue will be initiated, followed by an information campaign on the benefits of solar energy.

Impact and challenges (SWOT Analysis)

|

STRENGTHS |

WEAKNESSES - (ASPECTS TO IMPROVE AFTER THE EXPERIMENTAL PHASE) |

|

• Direct contribution to SDG 7 and SDG 16 • The main stakeholder (the UN) has strong financial and technical capabilities • It adopts an integrated approach following the HDP Nexus • It promotes community ownership of development and peacebuilding initiatives • It addresses conflict drivers |

• Institutional capacity is not explicitly addressed • The peacebuilding sector has a history of underfunding, decreasing trends, and difficulties in funds allocation • It does not address transborder conflicts |

|

OPPORTUNITIES |

THREATS |

|

• Its experimental nature opens a space for innovation in both sectors • Developing an innovative version of ‘conditionality’: in order to access aid for enhancing the energy sector, States must engage in dialogue with the local communities involved. |

• State-centrality in the application process could reinforce eventual repressive patterns • Growing geopolitical competition in developing countries could increase aid volatility, hinder community and country ownership |

The "Energy for Peacebuilding" program innovatively links peace, energy, and development by using energy projects as tools for community dialogue. Its high-risk, high-reward approach starts with peace and electricity access, progressing towards growth through increased energy consumption. The program’s people-focused, context-specific design aims for effectiveness despite challenges, like declining peacebuilding funding and shifting donor interests. Success depends on securing donor support aligned with a risk-tolerant, HDP-oriented mandate.

illuminem Voices is a democratic space presenting the thoughts and opinions of leading Sustainability & Energy writers, their opinions do not necessarily represent those of illuminem.

Purva Jain

Energy Transition · Energy Management & Efficiency

illuminem briefings

Energy Transition · Energy Management & Efficiency

illuminem briefings

Energy Transition · Public Governance

Deutsche Welle

Energy Transition · Energy Management & Efficiency

Climate Home News

Energy Transition · Public Governance

Politico

Energy Transition · Public Governance