· 4 min read

On March 31, the Flex Ranger, an LNG tanker 3 football fields long left Louisiana, USA with a capacity of 4 petajoules of primary energy. In Nunez de Bilboa, the Spanish company Iberdrola is running Europe’s largest solar farm, at 500 Megawatts (MW) covering 1,200 football fields.

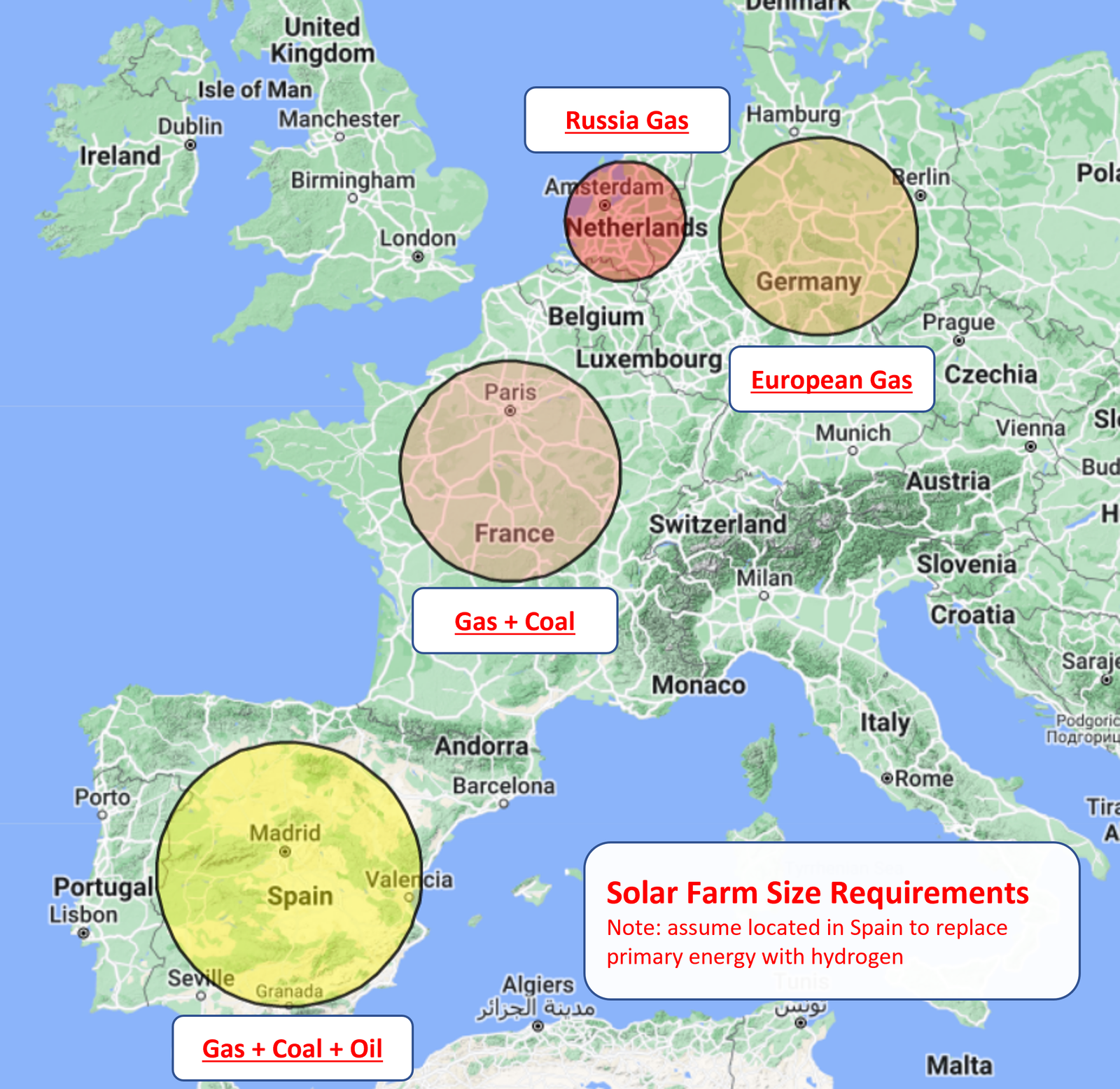

If you redirected the solar farm’s electricity to make another form of primary energy, green hydrogen, it would produce less than 2% of the content of the Flex Ranger by the time it docked in England 15 days later.

To produce the same primary energy in hydrogen as 1 LNG tanker, the solar farm would need to double in size to 1000 MW and run for a year.

But Europe needs more than 1 tanker?

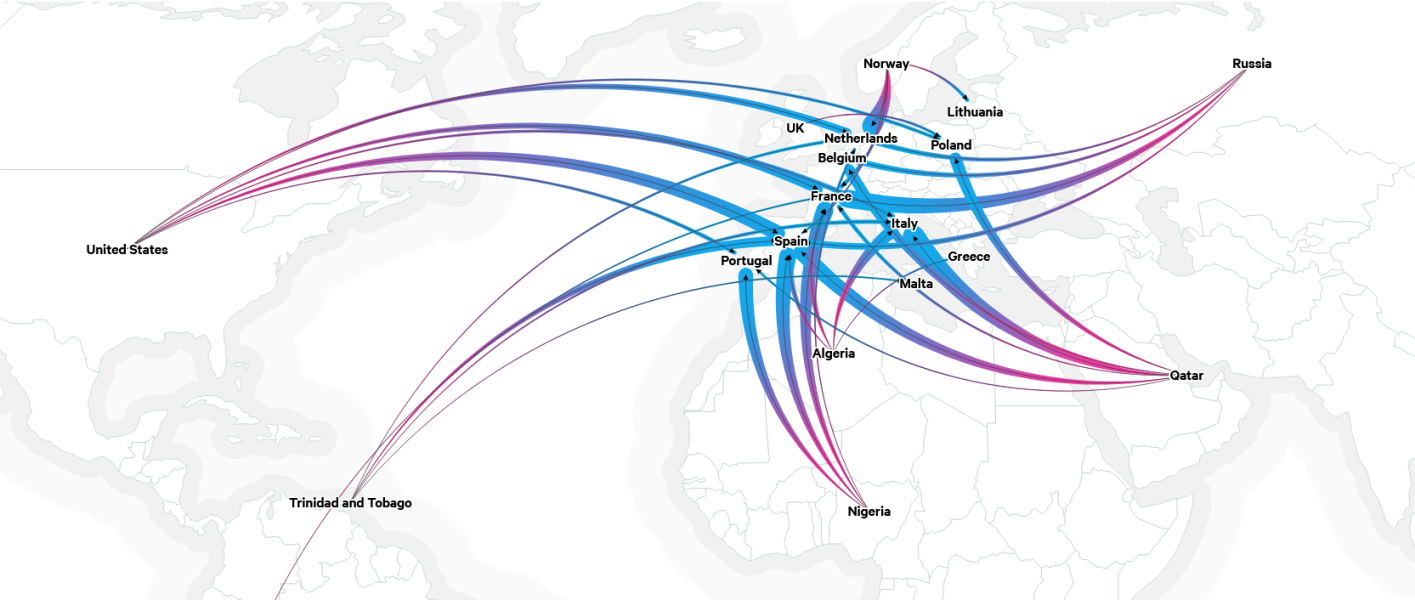

In 2020, Europe consumed 512 BCM of gas per year, with 185 BCM coming from Russia. Just to replace the Russian gas component, equal to 6,660 Petajoules would require 5 tanker deliveries every day.

Assuming you can expand around the Spanish solar farm, you would need to add another 1,920,000 MW of solar or roughly the size of the Netherlands to replace the 5 daily tankers.

And finally, to ween yourself off gas completely, will require an area a third of the size of Germany.

Can green hydrogen compete?

At €300m, the Núñez de Balboa solar farm offers an example of cheap electricity at roughly €29/MWh but depending on the price of electrolysers, the estimated price is in the range of €3-5/kg. With each kilo of hydrogen storing 33kWh of primary energy or roughly .11 MMBTU, the cost estimate would be €27-45/MMBTU. Meeting the EU’s goal of €1.8/kg by 2030 and you’re still looking at a price of €16/MMBTU.

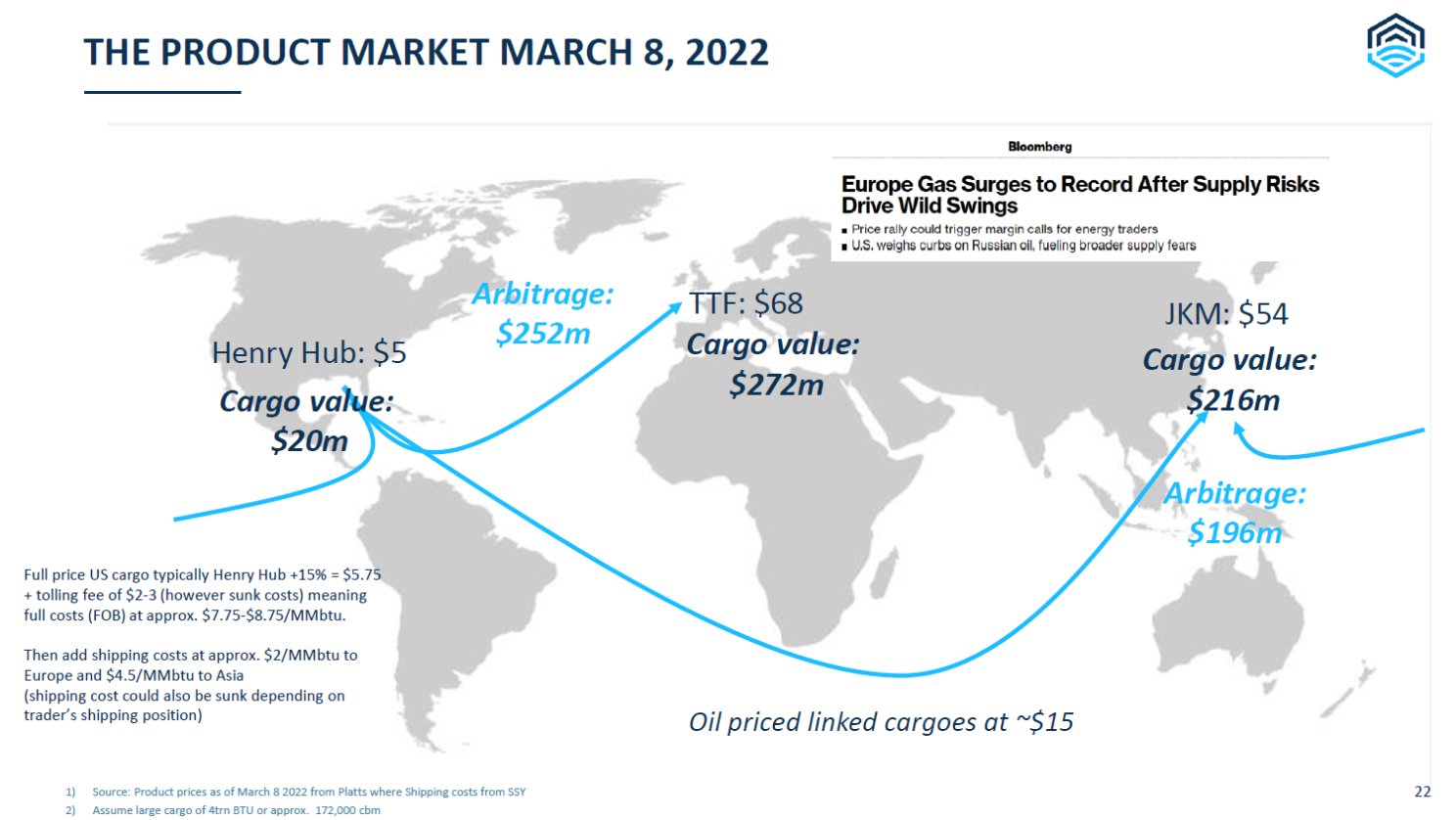

Traditionally, gas has been very cheap, piped in from Russia to power its industrial heartland, warm Europe during winter and more importantly balance out variable renewable energy. But with the invasion of Ukraine, this source looks tenuous at best.

The events have meant that while historically, European gas (Netherlands TTF) has averaged €5-8/MMBTU (€18-29/MWh) in recent months they have rocketed to €38/MMBTU (€130/MWh) making green hydrogen theoretically cheaper than pipeline gas.

What about liquified natural gas (LNG)?

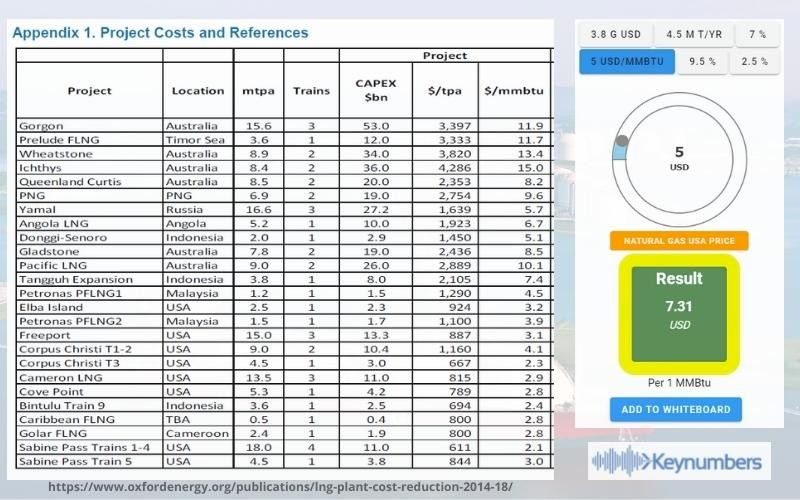

LNG is the liquification of natural gas to 600 times smaller than its original state. It requires about 10-12% of the gas to achieve this process and other operating costs approximately 2-2.5% of capex annually. Historically, the biggest cost was the initial construction. Both the LNG plant and shipping are expensive, effectively doubling to tripling the cost of gas and used as a last resort by energy poor countries such as Japan and Korea.

But as the industry has matured, these costs have fallen significantly. An Oxford Institute for Energy Studies report highlighted some of the cheaper LNG facilities are being built in the United States, benefiting from the proximity to existing infrastructure as well as access to cheap Henry Hub gas.

Adding in shipping and regasification, a landed cost of €9-12/MMBTU is theoretically possible, cheaper than the EU’s 2030 hydrogen target.

So LNG is cheaper long-term?

There’s one problem for gas and it involves the political aspirations in the form of the EU green deal and Fit for 55 target.

Europe is looking to reduce emissions by 55% by 2030 from 1990 levels. Replace carbon intense brown coal with natural gas, some efficiency gains and moving to electric cars would see the target within sight.

But the role of gas is now being questioned especially as tracking its origins is much more difficult via LNG.

A carbon tax would at €80/tonne would add €4/MMBTU to the cost of gas but this doesn’t include the growing issue of fugitive emissions, a problem highlighted by recent reports. While the IEA estimate fugitive emissions at 1.5%, American shale gas has reported with the help of new satellite technology methane plumes showing emissions in the range of 3.7% gross gas extracted with the potential to effectively double an already doubled price.

So where does this leave Europe?

Energy poverty is defined as spending more than 10% of income on energy needs. The reality is many especially in the poorer regions of Central Europe and the Balkans will be significantly impacted either by high energy prices or their governments avoiding the inevitable with increasing levels of debt.

There will be the usual calls for direct electrification in the form of electric vehicles and heat pumps which will reduce primary energy consumption by two thirds. The benefits of renewable energy will improve many for most of the time.

But the reality is for many, the end of cheap dispatchable energy will lead to the end of dispatchable lifestyles. Potentially this will leave Europe to start adjusting to the cyclical nature of renewables and learn to live seasonally?

illuminem Voices is a democratic space presenting the thoughts and opinions of leading Energy & Sustainability writers, their opinions do not necessarily represent those of illuminem.