· 10 min read

Introduction

The status of Nigeria as a developing country with high energy demand deepens its vulnerability to the adverse effects of climate change. As a party to the United Nations (UN) Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC),[1] there is an overwhelming need for the Nigerian government to take strategic steps that facilitate processes for future and more detailed agreements on responses to climate change and global greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. Particularly, a sustainable attempt towards addressing the dual crises of climate change and energy poverty necessitates a just and equitable transition to sustainable energy sources. However, more often than not, countries that are most vulnerable to climate change are faced with the challenge of being the least in the ability to afford investment for strengthening resilience due to the huge debts that burden their budgets.[2] Hence, many energy efficiency projects and programmes tend to be done partially as a result of the inadequate budget allocation to enhance its full implementation.

Thus, although the shift to more sustainable energy sources will undeniably enhance economic development, ensure electricity generation and supply security, improve energy efficiency and contribute to climate change mitigation, the challenge imposed by the cost implication of this arrangement requires due attention especially in consideration of Nigeria’s huge foreign debt portfolio. Therefore, where there exists a means through which Nigeria’s indebtedness to foreign nations can be reduced and such arrangement can also be instrumental in addressing any (if not all) of the dual factors that significantly threaten socioeconomic development and environmental sustainability in Nigeria,[3] it is only right that such an arrangement be embraced.

The concept of debt-for-nature or climate swap

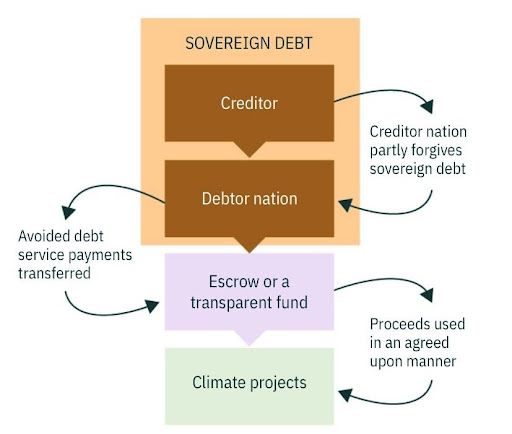

Debt-for-nature or climate (DfN) swaps are an indispensable arrangement for decreasing the debt burden of participating developing countries (debtor nations) and increasing the nations’ fiscal space for climate related actions/investments. It is a voluntary transaction that involves the purchase of external debts and a consequent reduction or cancellation of the developing nation’s debt at a discounted rate in the secondary debt market, in exchange for financial commitments towards environment-related action by the debtor nation.[4] DfN swap occurs when the accumulated debt of a nation is repaid through fresh discounted terms of agreement between the debtor nation and the creditor nation.

Typically, the creditor institution or country agrees to cancel part of a debt owed by the debtor country in exchange for the debtor country paying the avoided debt service into an escrow or any other transparent fund in its local currency, and the funds must be redirected to domestic projects that boost climate mitigation and adaptation activities which include but not limited to decarbonization projects, investment in climate-resilient infrastructure, renewable energy, biodiversity conservation etc.[5] This arrangement seek to relieve fiscal resources to enable the concerned governments improve protection actions that are environment-related without inducing a fiscal crisis or relinquishing spending on other development priorities.[6]

However, for countries with unsustainable debt, a DfN swap may not provide a universal solution unless it involves a sufficient percentage of a country’s debt and substantial relief.[7] Thus, DfN swap are not substitutes for debt restructuring,[8] rather, it can be utilized as a measure to support environment-related actions by the debtor nation through climate or conservation investment. By providing support for environment-related actions, this aligns with the provision of Article 4(4) of United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) which stipulates that the developed Country Parties shall assist the developing country parties that are particularly vulnerable to the adverse effects of climate change in meeting costs of adaptation to those adverse effects. Thus, the DfN swap/arrangement can complement other climate investment instruments and help with both environmental objectives and debt reduction/cancellation.

Although in my cases, it is more effective to address debt and nature or climate separately given that a simple climate-conditional grant tends to be more efficient on the climate side without the additional complexity of a debt-swap arrangement, however, and particularly, middle-income countries do not usually qualify for such grants, hence, the said concessional loans and grants from multilateral developments banks and bilateral donors are scarce in juxtaposition with the huge nature and climate financing need.[9] More so, when Corporate Debt Restructuring (CDR) is expected to produce huge economic dislocations and the debt-climate swap is expected to achieve debt sustainability and significantly reduce debt risks, DFN could rank superior to CDR in narrow settings. Again, when DfN swap is structured in a manner that places climate commitment de facto superior to debt service, DfN swap could be ranked above conditional grants.[10]

How debt for nature swap works

The initiative for the swap lies with the sponsoring body to establish dialogue with the government of the debtor country, the debtor country’s central bank and a domestic NGO. Upon approval, negotiations are made for a mutual agreement on the mechanism to be adopted in funding the potential project.[11] To ensure maximum fiscal space, the sponsoring NGO normally locates a potential donor, which may include governments, banks, public and private creditors etc. More so, investigations for discount levels are made at the international secondary debt markets for second-hand debts and here, debts could be bought for deep discounts.[12]

Notably, the DFN arrangement can be commercial – involving an NGO acting as the donor/broker, a debtor country and a creditor country; bilateral – involving two governments i.e the creditor country and a debtor country; multilateral – involving international transactions of more than two national governments.[13] Importantly, the amounts in question ought to be marginal relative to the debtor country’s debt burden. This is so because the opportunity costs (i.e. the value of the best alternative forgone in making a choice) of the freed funds are very low and to the extent that the reduced debt exceeds the new spending commitments for targeted environment-related project, the debtor nation(s) get fiscal relief through budget savings.[14]

Need to scale up debt-for-nature or climate swap

Undeniably, the rapidly growing population as well as the debt profile of some debtor nations particularly Nigeria exacerbates the pressure to pay off foreign debts in hard currency, leading to increased levels of natural resource exports at the expense of the environment.[15] This also extends to the level of investment being made towards activities that can generate revenue for servicing of these foreign debts. However, the financing of various projects may necessarily include investment in higher-carbon infrastructure. Where this is the case, these countries will be locked into that infrastructure for decades and consequently, intensify their energy transition and resilience risk.[16] Thus, the urgent need to incentivize and support these developing countries on initiatives that accelerate their low-carbon pathways cannot be overemphasized.

As a viable tool for reducing the external debts of heavily indebted nations, the DfN arrangement can be instrumental in cleaning a nation’s debt book and enhancing climate change mitigation and/or adaptation. This arrangement enables a debtor country to buy back part of its debt in more favourable terms and pay for conservation projects instead of servicing debt.[17] In recent times, in seeking global support and partnerships for the recently launched Energy Transition Plan (ETP), the Vice president of Nigeria; Yemi Osibanjo, proposed a Debt-For-Climate swap deal to facilitate a just transition to sustainable energy for African countries.[18]

More so, leveraging on the DfNs arrangement can upgrade a country’s sovereign credit rating thereby making government borrowing cheaper.[19] It also has the potential of creating additional revenue for countries with valuable biodiversity, by allowing them to charge others for protecting it. This is also applicable to carbon sequestration projects which absorb carbon dioxide from the atmosphere or a smokestack and are instrumental to the sustainable transition to a lower carbon economy.[20] Notably, the existence of tropical forests in many developing countries with huge debt portfolio, presents an opportunity to trade off such bad debts in the secondary debt market in return for environment-related projects. This is so because as deforestation exists as a source of carbon emission into the atmosphere, investing in forest regrowth projects through DfN arrangement can serve as a carbon sequestration project, with the tropical forests serving as carbon sinks.[21]

In many cases, indebted developing countries encounter difficulty in meeting their hard currency debt obligation and defaulted. However, reducing foreign debt and allowing for portions of it to be paid with local currency while increasing funds for the environment can improve environmental conditions in developing countries and relieve the debtor country’s difficulties in procuring sufficient hard currency to pay off its debts.[22] This can enhance an increase in the international purchasing power of the debtor nation.[23] Conversely, loss of purchasing power can greatly impact investments made by long-time investors whose contributions are important for economic development. As this arrangement can positively influence carbon markets, impliedly, it can play a significant role in spurring sustainable energy deployment by directing private capital into climate action, diversifying available incentive structures especially in developing nations, improving global energy security and providing an incentivize for clean energy markets when the price economics looks less compelling.[24]

Conclusion

The huge debt portfolio of several developing nations necessitates the squeezing of their budget, decreasing their fiscal spending on the environment and consequently, being marginally able to finance environmental conservation initiatives. This occasions an inability to meet up with environmental protection commitments and the continuous increase in high-carbon infrastructure in a bid to raise funds for debt servicing. In due time, this destruction of the ecosystem will increase the difficulty for these countries to achieve their economic and social development goals while battling with the adverse impacts of their key sectorial activities on the climate.

If nations must meet the target of the Conference of Parties (COP27) in addition to the treaties and protocols geared towards environmental protection, nations need to accelerate the exploration of DfN arrangement. Considering Nigeria’s debt portfolio as well as its high reliance on fossil-based energy sources that significantly contribute to climate change, it is recommended that the Nigerian government should embrace more programmes for the setting-off of negotiations with creditor nations and take advantage of this climate finance structure as this guarantees a tripartite win-win situation whereby its heavy indebtedness can be reduced alongside a fiscal relief through budget savings, substantial funds can be made available upfront for long-term climate change mitigation and other environmental conservation projects and there will also be an increase in Nigeria’s low-carbon infrastructure in support of a just energy transition pathway.

On the other hand, developed creditor countries and other relevant participants in a DFN arrangement should support the increase in the fiscal space that is created by climate or nature swaps through improving the terms of the transaction to include as large a share of a country’s debt as possible, ensuring a carefully designed secondary-market for repurchasing the debt at the lowest possible price, and minimizing the cost of financing the debt buy-back.

Although DFN swaps may not provide a universal solution for confronting climate change or struggling with debt, nevertheless, they can be ramped up to consolidate existing instruments and strengthen resilience in countries vulnerable to climate change and loss of natural resources at a time when financing is limited.

References

- Nigeria is also a party to other framework such as the Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs), Kyoto Protocol, Paris Agreement.

- Kristalina Georgieva, Marcos Chamon and Vmal Thakoor, ‘Swapping Debt for Climate or Nature Pledge Can Help Fund Resilience’ (IMF Blog, December 2022) <https://www.imf.org/en/Blogs/Articles/2022/12/14/swapping-debt-for-climate-or-nature-pledges-can-help-fund-resilience> accessed 7 January 2023.

- These factors include energy poverty and climate change.

- Samuel Ehiwe, ‘Debt-for-Nature swaps: An Aspect of Climate Finance’ (LinkedIn, December 2022) <https://www.linkedin.com/posts/samuel-ehiwe-34b578159_sustainability-project-finance-activity-7010924446521659392-c2CR?utm_source=share&utm_medium=member_ios> accessed 26 December 2022.

- Agency Report, ‘Energy Transition: Nigeria Proposed Debt-for-Climate Swap Deal’ Premium Times (Washington DC, September 2022) <https://www.premiumtimesng.com/news/headlines/551993-energy-transition-nigeria-proposes-debt-for-climate-swap-deal.html> accessed 8 January 2023.

- Georgieva, Chamon and Thakoor (n 2).

- Ibid.

- However, restructuring is not often available to countries until their debts become unsustainable and their market access is lost - Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ehiwe (n 4).

- Charles C Anukwonke, ‘Debt-for-Nature Swap as an Option to Forest Conservation: A Case of Nigeria’ [2015] 3(3) Basic Research Journal 29-37, 30.

- Ibid.

- Ibid 31.

- Ehiwe (n 4); Georgieva, Chamon and Thakoor (n 2).

- Anukwonke (n 11) 30.

- Leigh Elston, ‘How Debt-for-Climate Swaps Can Help Fund the Energy Transition’ (Energy Monitor, May 2021) <https://www.energymonitor.ai/finance/sustainable-finance/how-debt-for-climate-swaps-can-help-fund-the-energy-transition/> accessed 24 January 2023.

- Anukwonke (n 11) 33.

- Agency Report (n 5).

- Georgieva, Chamon and Thakoor (n 2).

- Ibid.

- Noelle Eckley Selin, ‘Carbon Sequestration’ <https://www.britannica.com/technology/carbon-sequestration> accessed 8 January 2023.

- Anukwonke (n 11) 30.

- Ibid 33.

- The Editorial, ‘Osinbajo Advocates DFC, Greater Global Carbon Market Participation for African Nations’ Vanguard (September 2022) <Osinbajo advocates DFC, greater global carbon market participation for African nations - Vanguard News (vanguardngr.com)> accessed 15 January 2023.

Future Thought Leaders is a democratic space presenting the thoughts and opinions of rising Sustainability & Energy writers, their opinions do not necessarily represent those of illuminem.