Crunch time for biodiversity – will it be third time lucky?

· 8 min read

The world failed to achieve the 2010 and 2020 biodiversity targets set by the Convention on Biodiversity - in December it will adopt a third set of targets to 2030

The 1992 ‘Rio Earth Summit’ raised high hopes we could turn around the declining state of our global environment. The Convention on Biological Diversity (‘the Convention’) was opened for signature at the Summit, along with the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (‘UNFCCC’)[i].

The Convention has three objectives, the conservation of biological diversity, the sustainable use of its components, and the fair and equitable sharing of the benefits arising out of the utilization of genetic resources.

In an effort to achieve these objectives, the 196 Parties (countries) to the Convention agreed on global biodiversity targets for 2010 and for 2020, and are now in the process of finalising negotiations on a new Post 2020 Global Biodiversity Framework (’the Framework’), to be adopted in Montreal at the 15th meeting of the Conference of the Parties to the Convention in December this year (‘CBD CoP15’). Despite several years of negotiations, including intense discussions in Geneva and Nairobi in recent months, much remains to be agreed.

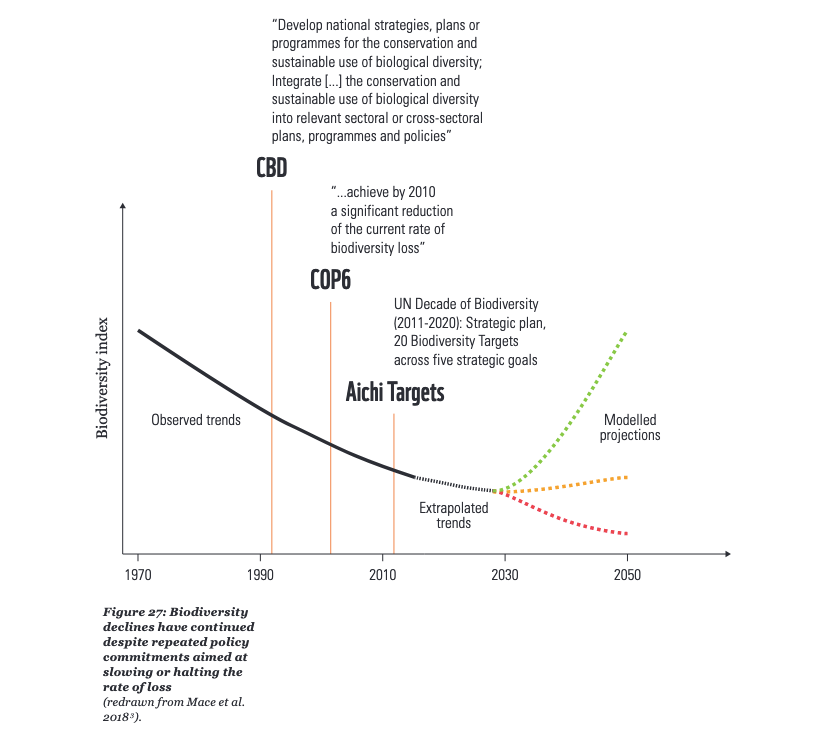

A single biodiversity target for 2010 was adopted in 2002 at CBD CoP6 in The Hague[ii]. It was not met. A set of 20 biodiversity targets for 2020, known as the Aichi Biodiversity Targets, were adopted in Nagoya in 2010 at CBD CoP10. They were not met either, although progress has been made against six of the targets, and in particular the target on the geographic area to be covered by protected areas and other effective area-based conservation measures.

In 2019, the UN IPBES (the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services) released its Global Assessment Report on Biodiversity and Ecosystems Services, which says that one million species will go extinct within coming decades if we continue on our current trajectory. Among its many other findings, IPBES tells us that 75% of the planet’s terrestrial surface is significantly altered, 3% of the ocean surface is considered as wild, and that we have lost 85% of wetlands by area, despite having a Convention on International Wetlands since 1973.

A graph in the WWF 2018 Living Planet Report shows that the adoption of the Convention, along with its various strategies and targets, made no discernible difference to the sharp decline in wildlife. WWF’s 2022 Living Planet Report finds that over the past 50 years we have lost 69% of the world's wildlife[iii].

At times, I wonder whether the adoption of a dedicated convention on biodiversity was a double-edged sword. On the one hand it demonstrated political and legal commitment to the issue, yet on the other hand it provided a forum for the global biodiversity community to meet, and agree upon biodiversity strategies and targets, largely detached from the agencies and sectors that determine the fate of biodiversity. There is an old expression that 'the tail does not wag the dog', and the biodiversity agenda has not (yet) shaped the development agenda.

The evidence clearly shows that, despite all these well-intentioned global initiatives to protect biodiversity, something is not working. The time has come for us to use the ‘f’ word. While we can see some local successes, global efforts to save biodiversity more broadly have largely failed.

We need international conventions, global summits, strategies and targets, but they have their limits and their success cannot be measured by how many we have, or how many decisions are adopted, but by how they impact what is happening on-the-ground. By that measure, the Convention has, thus far, failed. I am not alone in that view.

In an interview in August 2022 on ‘A Thirty-year reflection of the 1992 Rio Conference on the Environment and Development, “Have States failed?”’ Ambassador Tommy Koh described the Convention as having been “a failure”, yet he also stressed his enduring belief in the value of international environmental law[iv].

Notwithstanding the world’s failure to deliver against its biodiversity targets, the Convention has provided the framework for action by Parties, a means to broadly monitor progress against commitments, and, in some instances, find avenues to advance compliance.

It is worth persisting with the Convention. It is still the best global forum we have to reach agreement on how to collectively halt and reverse the current disturbing trends of biodiversity loss. But after several rounds of failure, CBD CoP15 is crunch time, for the credibility of the Convention itself and, more importantly, the planet’s biodiversity.

Similar sentiments have been expressed by Stephen Guilbeault, Minister of Environment and Climate Change for Canada, the host country for CBD CoP15 and the Convention’s Secretariat, which is based in Montreal. While Canada is hosting the CoP, China holds the Presidency.

At the core of CBD CoP15 rests the fate of the draft Post 2020 Global Biodiversity Framework, which currently includes 22 draft targets, including one on the conservation of at least 30 per cent of global land and sea areas (‘the 30x30 target’). Listing a number of targets, has resulted in a scramble by Parties and stakeholders alike, to ensure their priorities are included in them.

Unlike the 2015 Paris Agreement, the draft Framework does not include a clear overarching target or require Parties to outline Nationally Determined Contributions (‘NDC’), which set out how each Party is contributing towards achieving the desired collective ends[v]. Rather, it has a process known as National Biodiversity Strategies and Action Plans (‘NBSAPs’), which have not generated the same level of political attention or scrutiny as NDCs, which the draft Framework seeks to address.

We can be confident that a Framework will be adopted in Montreal. The question is how ambitious it will be, whether its implementation will be adequately financed, and how the Convention will address compliance with the agreed Framework. In this context, it is worth noting that the Convention does not have a compliance mechanism and it works on the basis of consensus[vi].

Parties to the Convention have considered taking decisions through voting where there is no consensus, which is provided for under some other global conventions[vii]. However, the text on voting in the Convention’s rules of procedure remain in brackets, meaning it is not yet agreed, and is highly unlikely to be accepted. One can see the rationale for consensus on a global framework of this nature, but it invariably makes for compromise, with implications for the level of ambition.

The Convention, and its Executive Secretary Elizabeth Mrema, have been working hard to extend its reach beyond the traditional biodiversity community. Recent creative initiatives, such as the Taskforce on Nature-related Financial Disclosures and the Finance for Biodiversity Pledge, reflect efforts to broaden the constituency with an interest in the Convention, and high-level events on biodiversity have been held at the UN General Assembly and at UNFCCC CoP27 in Sharm el-Sheikh.

Parties negotiate the Framework, but implementing it requires ‘all hands on deck’. The draft acknowledges a broad range of stakeholders, including the important roles and contributions of indigenous people and local communities, with indigenous lands making up around 20% of the Earth’s territory, and containing 80% of the world’s remaining biodiversity.

And there are bright spots as we head towards CBD CoP15, including the serious efforts at UNFCCC CoP26 to place biodiversity at the forefront of the response to climate change – mitigation, adaptation and building resilience – with a renewed interest in nature-based solutions (or ecosystem based approaches), the High Ambition Coalition for Nature and People, which now has over 100 countries championing the 30x30 target, and new pledges for financing biodiversity conservation.

Will all this outreach and momentum translate into a successful outcome from CBD CoP15, with the adoption of an ambitious, adequately financed, and implementable Post 2020 Global Biodiversity Framework? We will know by the end of the year what sort of Framework we have, but it is then up to Parties, together with all stakeholders, to live up to our commitments.

“Implementation, implementation, implementation” was the catch cry of the Executive Secretary of the Convention, Braulio Dias, when he took over the reins of the Secretariat following the CBD CoP10 in Nagoya in 2010 where the 2020 targets were adopted. It bears repeating.

For the sake of the world’s biodiversity, and our prosperity, let’s hope it is third time lucky.

[i] Together with the UN Convention to Combat Desertification, open for signature from October 1994, these three conventions are collectively referred to as ‘the Rio Conventions.’

[ii] The 2010 biodiversity target was “to achieve by 2010 a significant reduction of the current rate of biodiversity loss at the global, regional and national level as a contribution to poverty alleviation and to the benefit of all life on Earth.”

[iii] The 2020 global Living Planet Index shows an average 68% (range:-73% to -62%) fall in monitored populations of mammals, birds, amphibians, reptiles and fish between 1970 and 2016.

[iv] “A thirty-year reflection of the 1992 Rio Conference on the Environment and Development with Ambassador Tommy Koh: “Have States failed?” National University of Singapore, August 25, 2022.

[v] Namely limiting global temperature rises to “well below” 2 Celsius above pre-industrial levels, while aiming to limit heating to 1.5 Celsius.

[vi] There is an Ad Hoc Open-ended Working Group on the Review of Implementation of the Convention (WGRI). and the draft Framework includes text on enhanced mechanisms for planning, monitoring, reporting and review.

[vii] By way of contrast, CITES (Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora) does allow for voting. On substantive issues a two third majority of Parties present and voting is sufficient to decide a matter. However, the quid quo pro is that Parties can enter a reservation against the listing of species, meaning the Convention doesn’t apply to that country in relation to the species.

This article is also published on the author's blog. Illuminem Voices is a democratic space presenting the thoughts and opinions of leading Sustainability & Energy writers, their opinions do not necessarily represent those of illuminem.

Simon Heppner

Effects · Climate Change

illuminem briefings

Pollution · Nature

illuminem briefings

Biodiversity · Nature

CGTN

Renewables · Nature

earth.com

Carbon Capture & Storage · Biodiversity

Euronews

Pollution · Cities