Developing sustainable finance for a Net Zero Indonesia — opportunities and challenges

· 7 min read

International climate discourse centres around the responsibilities of major emitters — often focused on the United States, China, India and the EU. Discussions regarding National Determined Contributions, loss and damage, and ‘common but differentiated responsibility’ have often highlighted the unequal contribution of a handful of countries to climate change.

However, some countries are not typically represented in this discourse. Namely, Indonesia — the world’s 4th most populous country — is projected to become the world’s fourth-largest economy by the mid-21st century. In light of that, the climate ambitions of Indonesia strongly matter, particularly if ASEAN is to achieve its regional climate ambitions.

While Indonesia’s economy is rapidly rising, it remains a prolific extractor, exporter and consumer of coal, and is the world’s 8th biggest emitter, having emitted 112 million metric tons of coal in 2021. Combined coal resources in the Indonesian regions of East Kalimantan, South Sumatra, and South Kalimantan equal 87 billion tonnes, and coal contributed $38 billion in export earnings in the first seven months of 2021.

In alignment with its Paris commitments, Indonesia aims to reduce its greenhouse gas emissions by at least 31.89 percent by 2030 relative to its business-as-usual scenario. However, it is perfectly possible this could be upwards of 43.30 percent by 2030, particularly with support from the international community in technology and financing. However, the current climate ambition laid out by Indonesia is deemed as “highly insufficient”.

For Indonesia to finance its 2030 climate goals, it requires an investment of USD 250 billion by 2030. However, the government can only meet about 34% of the total investment needed to achieve its NDC targets. Exacerbating this issue, in October 2021, Moody’s reported that 31% of the country’s on-balance sheet loans are credited towards industries with significant carbon transition risk, the third highest percentage in the G20.

Fortunately, Indonesia is beginning to establish strong precedents for its sustainable finance future, especially in light of its recent G20 presidency. Of particular note, the country launched a US $20 billion Just Energy Transition Partnership (JETP) focused on the mobilisation of renewable energy, launched at the G20 with its global partners in November 2022. Likewise, the launch of Indonesia Green Taxonomy 1.0 in January 2023, paved the way for investor confidence in the characteristics and direction of Indonesia’s net zero economy. This is complemented by the Sustainable Finance Roadmap Phase II (SFR II), which outlines how the financial sector will move towards a more sustainable trajectory over the next few years (2021-2025), with Indonesia’s Green Taxonomy at the centre.

However, there are still notable barriers to the uptake of decarbonisation finance in Indonesia. Importantly, Indonesia must grapple with its inadequate capital structure and composition — being relatively shallow, and with the banking sector accounting for 76% of financial sector assets. Bank lending, focused on shorter term project cycles and returns, is not typically geared towards sustainable financing without adequate government guarantees, underwriting or regulatory architecture. To assist with this, the Asian Development Bank’s Energy Transition Mechanism (ETM), focused on providing blended financing from public, private and philanthropic sources, to retire coal fired power stations across Asia. This has a focus on social safeguards, reducing adverse social outcomes from closing coal fired power stations.

Already, the ETM is working closely with Indonesia’s Cirebon Electric Power (CEP) — a publicly owned power utility — to close Cirebon-1, a 660 megawatt (MW) coal-fired power plant in West Java. This is an early stage project, but it could provide precedent and scaffolding for future financing instruments and models for a just and sustainable energy transition in Indonesia.

However, much of Indonesia’s electricity market is run by PLN, meaning political factors and government relations matter substantially more than engaging with market actors. PLN’s buy-in for decarbonisation and the ETM is absolutely necessary in this context, meaning regulatory confidence and government stability must be achieved to ensure long term confidence in the management of sustainable finance funds.

Additionally, the renewables market is still relatively immature in Indonesia, dampening investor confidence. De-risking financial investments could lower financing costs, derived from the heightened market, credit, political and regulatory risks in investing in Indonesia. The aforementioned JETP and ETM are good starts — consisting of concessional loans and guarantees necessary to de-risk investment and therefore, increase investment in green energy. However, to sustain and scale the uptake of green energy, there must be robust sustainable finance regulatory architecture in Indonesia, to avoid some of the previous regulatory ambiguity and risks of investing in Indonesia.

While Indonesia’s Green Taxonomy is impactful and formative regulation, it has been designed mainly as a guidance, rather than a mandatory instrument. It also experiences issues of interoperability. As numerous other countries develop their own sustainable finance taxonomies, Indonesia must consider how its own green taxonomy interoperates with other global and importantly, regional, taxonomies. Doubts regarding the interoperability of Indonesia’s green taxonomy will undermine trust, confidence and interest from sustainable financiers, in addition to adversely affecting Indonesia’s ability to be a player in the regional and global green economy.

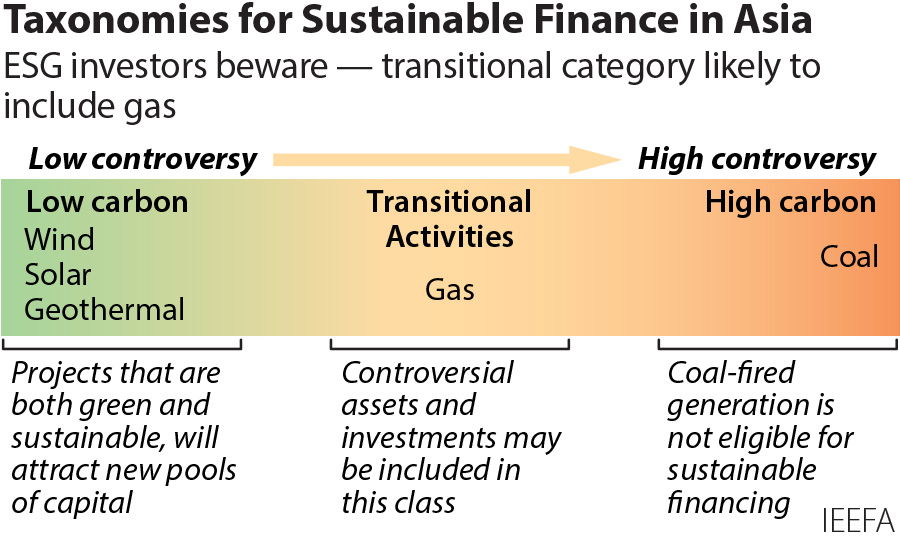

For example, the EU taxonomy, considered one of the world’s leading, has far more stringent Technical Screening Criteria (TSC), focused on particular, targeted economic activities and social and environmental safeguards — ensuring social and human rights. This contrasts with the Indonesian or even the ASEAN Taxonomy, focused on a ‘traffic light’ system, similar to what is seen in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Taxonomies for sustainable finance in Asia

This taxonomy focuses on 3 broad categories, including a yellow (transitional) category. In the case of Indonesia’s taxonomy, 919 sectors and sub-sectors are covered, including:

Many critics highlight the problematic nature of the ‘yellow’ (transitional) category. Indonesia’s unabated oil and gas projects could be considered ‘transitional’, hence bringing into question the sustainability credentials of Indonesia’s taxonomy. Furthermore, projects in this category can be considered ‘not significantly harmful to the environment’ — at odds with scientific consensus towards the sustainability credentials of these types of projects.

Hence, this produces substantial market risk. There needs to be confidence in Indonesia’s taxonomy from sustainable financiers and its ability to harmonise with other sustainable finance taxonomies. This is particularly in an era where more sustainable finance taxonomies are being created, and sustainable finance is proliferating at a regional and global level.

While Indonesia’s green transition is gaining traction, there are still key regulatory and risk dimensions stultifying its net zero journey. Typical market concerns regarding credit, regulatory and political risks remain, with some possible hope on the horizon in light of the JETP, ETM and Green Taxonomy. However, it is still early days, and these initiatives are nascent and rather experimental. Over the next 5-10 years, as climate change becomes more damaging and Indonesia’s role as a climate actor growing, it is imperative that Indonesia overcome the regulatory inadequacies and market risks that have stubbornly persisted in the country, hindering their transition to date.

illuminem Voices is a democratic space presenting the thoughts and opinions of leading Sustainability & Energy writers, their opinions do not necessarily represent those of illuminem.

Charlene Norman

Sustainable Business · Sustainable Finance

illuminem

Climate Change · Environmental Sustainability

Responsible Investor

Sustainable Finance · ESG

Luxembourg Times

Sustainable Finance · Public Governance

ESG Today

Carbon Removal · Sustainable Finance

illuminem

Corporate Sustainability · Sustainable Business