· 9 min read

I am, after years of debating — and saving — finally having solar panels fitted to the roof of my house, combined with a home battery pack. The soaring costs of gas and electricity in the UK have finally tipped the balance to make this financially justifiable — the ‘payback period’, after which the electricity saved and produced pays back the cost of installing them, has gone down from 10 years to 6. I’m hoping that in a year’s time, the performance of my panels will be just as good as The New Climate’s Frank Parker’s—which he wrote about here.

The debate around solar

But what of the environmental justification? This, as an environmental writer, seems obvious: solar is clean, green, renewable energy. By installing it, I will be generating a substantial part of my electricity from the sun alone. Also by doing so, I am taking less electricity from the national grid, reducing overall demand — and in peak months, when I can’t use all I produce, I will be adding some renewable energy back to the grid (albeit at a very low rate for me, and a very good rate for them. The feed-in-tariffs that used to guarantee payment for all electricity generated and exported for 20 years, were scrapped in 2019. The FIT was as high as 54p/kWh for electricity generated in 2011; now I can expect 4.1p/kWh, and only for power I export).

However, as the whole world struggles with rising energy costs, the current scramble for solar generation and storage has seen some pushback against the ‘obvious’ justifications above. This tweet from Lion Hirth, Professor at Hertie School and an expert on energy markets, caught my eye.

Most of the replies were along the lines of this one from Robert Ferry, Co-founder of @poweredbyart:

“It will be nearly impossible to fully decarbonize without them. The promise of grid-connected smart homes may finally be coming to pass.”

i.e., private solar and battery packs = good. (FWIW, my own reply to Hirth was “Surely they reduce the household(s) demand on the grid, which is good for the centralized system/society?”)

But what of Hirth’s point — might this not good be for society? I am of course in a privileged position to be able to afford and install domestic solar panels (albeit, by the skin of my teeth). Despite my seeing this as an environmentally altruistic choice, is it in fact the opposite? In a world with finite materials, would they be better used for centralised infrastructure and mega-solar farms? Am I, in some ways (and there is no worse crime in English culture) jumping the queue?

The evidence

Turns out, a team of researchers already posed this question in a Nature paper in 2021.

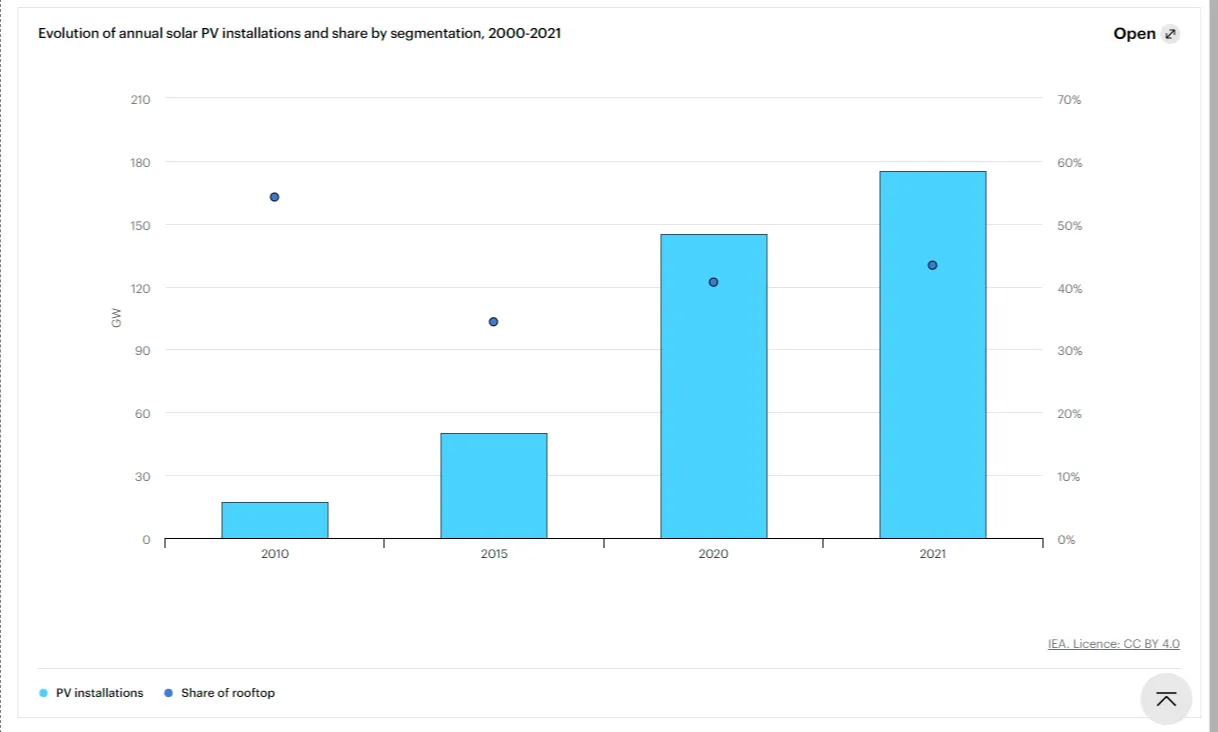

The authors estimate that the total surface area of all the rooftops in the entire world is around 0.2 million square kilometres — similar to the size of the UK. And you wouldn’t need to plaster them all with solar panels to meet the world’s current electricity needs: in fact, only half of them would suffice. Amazingly, the study led by Siddharth Joshi of the SFI Research Centre for Energy, Climate and the Marine (MaREI), Ireland, found that between 2006 and 2018 the installed capacity of rooftop solar had grown from 2.5 GW to 213 GW — an 85-fold increase globally. It accounted for 40% of all solar PV globally and nearly one-fourth of the total renewable capacity additions in 2018. And despite the pandemic, the growth has continued to snowball, with the IEA forecasting that at least 190 GW will be installed each year from 2022 onwards.

In a subsequent interview, Joshi told Forbes,

“Rooftop solar has two unique attributes that set it apart from other forms of renewable energy generation: fast deployment, and decentralised citizen-driven uptake. These attributes lend it specific advantages over other renewable generation technologies”,

adding that rooftop solar

“brings significant advantages in terms of broad participation of society in the energy transition to a low carbon future.”

In particular, India and China have a sizable potential for rooftop solar photovoltaics, along with the lowest cost for the deployment of these technologies — considering the latter manufactures most of the world’s solar PV.

Challenges of solar

The IEA outlines the challenges of solar, namely that upfront costs remain a significant obstacle and multi-family buildings and apartment blocks make the split of production and billing among different tenants remains a complex issue. But in summary, said the IEA, the

“barriers are social, financial, psychological, and regulatory rather than technical. The technology has reached such a level of maturity that it can be deployed easily everywhere”.

Similarly, opposition to industrial-sized solar farms in the countryside is growing. I’m not anti-solar farms by any means — especially when combined with sheep grazing and wildflowers for insects. But existing rooftops are, by definition, already brownfield sites. Why build on greenfield sites unless we really need to? CPRE, the countryside charity, points out that,

“Germany has focused on rooftops first, with 80% of its solar power coming from panels that generate little public opposition”.

CPRE is calling on the government to “adopt a renewables strategy that prioritises rooftops, surface car parks and brownfield sites”.

If implemented quickly, they say, “the policy could drastically reduce energy bills during the cost-of-living crisis and speed up the transition to net zero”.

What then?

The Nature authors say that the global electricity supply cannot rely on a single source of generation. So no, rooftop solar isn’t about to power the world. The equipment required to store solar power is still expensive, while solar panels can’t deliver power for heavy industry, which requires very large currents. That said, they write,

“Despite this, rooftop solar has huge potential to alleviate energy poverty and put clean, pollution-free power back in the hands of consumers worldwide. If the costs of solar power continue to decrease, rooftop panels could be one of the best tools yet to decarbonise our electricity supply”.

Well, that’s me sold (which is just as well, because I’ve already bought them).

This article is also published on the author's blog. illuminem Voices is a democratic space presenting the thoughts and opinions of leading Sustainability & Energy writers, their opinions do not necessarily represent those of illuminem.