Climate change: it isn’t only about climate

· 8 min read

Humans have been consuming energy since time immemorial (Smil, 2017a). We need energy to survive. Without the conversion of sunlight to phytomass, life as we know it couldn’t have existed (Smil, 2017b). The prime movers of energy were first to animate such as ourselves, draft animals using what is called somatic energy, and gradually inanimate movers were introduced. In short, the world breathes energy, from our daily commutes to air travel, and from brick-and-mortar manufacturers and corporations to the sophisticated digital world. Without energy, we wouldn’t be doing what we are capable of right now - some may say that it would have been better.

However, in this complex system, i.e. the world, any variable, through its interaction with the system, can have effects that go beyond what we could ever imagine. The relentless use of energy - we have consumed more energy since the 1950s than in the past 12,000 years - and deforestation of essential “carbon stores”, such as the Amazon rainforest, has reached their highest since 2008 and our unbridled culture of consumerism, especially the “tech-lust”, has lead to a dystopian nightmare. Simple things such as the textile industry contribute more to carbon emissions than flights and shipping combined. The US, China, and EU amount for half of the global carbon emissions while 20 companies dealing with fossil fuels account for more than one-third of greenhouse gas emissions. However, we get more than 80 percent (84 percent to be precise) of our global energy supply from hydrocarbons.

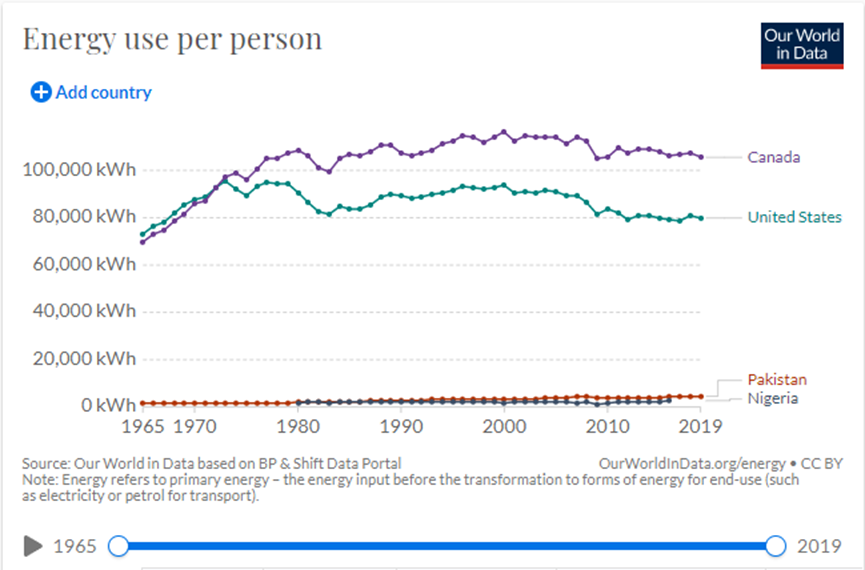

To delineate a proper time in history when this exploitation of our environment began is a difficult task. The rate of growth of the global population seems to have a directly proportional relationship with the use of energy (evidently it makes sense as each of us requires energy to survive). However, that rate of growth of the use of energy hasn’t been subjected to a uniform distribution. And here is where the topic gets interestingly tricky. The Age of Exploration followed by the colonization of various regions across the world gave a certain group of people the opportunity to harness nature for their own use. But that left a gap, a distortion in the relationship between what is called the Global North and Global South - terms which themselves are products of colonization. The gap still persists. Energy consumption per person in the U.S. was about 80,000 kWh compared to 4600 kWh in Pakistan.

Source: Our World in Data

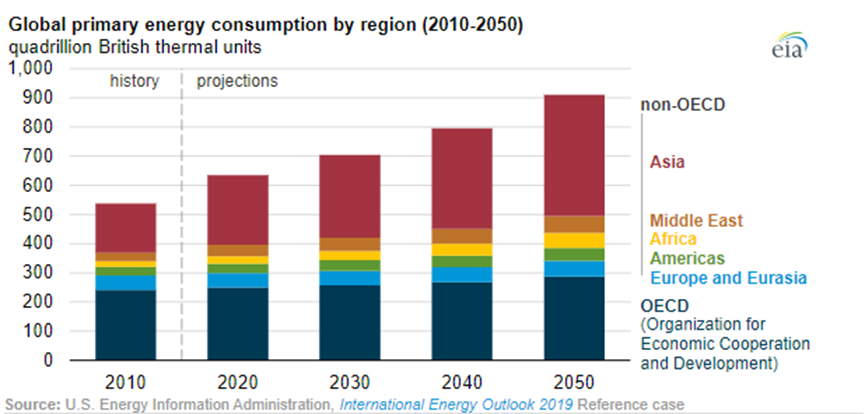

The point is that we all require energy and its use is growing. The EIA estimates a 50 percent increase in energy consumption by 2050, mostly driven by non-OECD countries. Countries that are developing will, probably, increase their energy use. Of course, the efficiency of systems can be increased but it has been improving ever since.

The question then becomes what do we do in order to tackle this gravely serious issue of climate change and carbon emissions?

We now turn to the Phronesis. The importance of balance is universally appreciated and lauded and endorsed and advised. Too much of anything is not good or desirable - it is almost a universal truth. I believe the answer to a greener, sustainable, environmentally friendly future is in striking this balance.

But first I will identify what I have understood to be the two main themes or approaches that the discussion veers to while debating about the ways we can solve the issue of climate change and ecological justice.

(Of course, the use, applicability, and effectiveness of these technologies merit a separate discussion).

In accepting the second, one is indirectly rejecting the first or rather accommodating the idea that we can continue to progress (grow) with the current model of capitalism but that technology will help us do it in a more environmentally friendly and sustainable way. This relates to debates about Growth and Degrowth. In accepting the first, one is, in a way, rejecting the second approach: technology will not help us until or unless we change the way we live. It is time to rethink the world in a different image!

The answer once again may be in the Phronesis. Practical solutions. Is it practically possible for the world to let go of the current model of consumption? In this world, one may ask, do we have the "aires": billion, million, and trillion? Do we have private property? Regarding the culture of consumerism, is it practically possible to let it go? Companies, consumption, cash - it is as if these threads are now a critical, crucial part of the tapestry of the fabric of the way and means with which we interact with our environment!

As mentioned above, digital apparatus, from our mobile devices to computers and the lithium used in electric vehicles to other green technologies, might not be so green. Everything requires, directly or indirectly, some damage to the environment. Google Baotao, a city in inner Mongolia, and see the images of what is a toxic lake, a product of the tech products we use! Rare Earth elements are the linchpin of the modern global economy, from aircraft and missiles to iPhones and microwaves. However, all are mined and extracted. What is the alternative? Electricity used by major data centers, which are estimated to have a larger carbon footprint than the whole aviation industry, in the world comes from non-renewable sources.

If not for these technological advancements, which are indeed not environmentally friendly, the world would have literally come to a halt during this pandemic.

Similarly, as Arundhati Roy highlights in her essays about the effects that mega-dams or other projects of such nature have had on the indigenous people, such mega-projects usually displace people internally AND destroy natural habitats. But what about the principles of utilitarianism? What if building that dam would have benefitted hundreds of thousands of other people? What do we choose? We are now treading into the field of philosophy. We’d rather not.

While it is extremely important, rather crucial, to highlight the negative effects of these trappings of modernity (depending on what we call modernity), it is equally significant to provide alternatives.

If we want to curb our technological use and infrastructural development, we are automatically following the first approach that raises some very potent and relevant philosophical and ideological aspects of development and growth but doesn’t provides a practical alternative. A debate to change the way we live or have lived can be useful but too much fixation on this abstraction only without any practical solutions can cost us precious time.

Can we go on with our relentless, reckless, unbridled consumption and exploitation of the environment? The answer to that is a resounding NO! Not at all. We can't afford it. This is where the concept of balance, restraint, and not doing too much of anything comes in - an idea as old as humanity with almost universal acceptability and applicability. We have to curb deforestation, save ocean life, reduce plastic use and mining, drill less, and so on and so forth!

In doing so, technology can be a great enabler in making this shift. However, we need government regulations and efforts by the media, citizens, civil society, and businesses, especially those most responsible for emissions.

The discrepancy between the emissions of the richest 1 percent and the lowest 50 percent is extraordinary. The former is 70 million people responsible for 15 percent of global carbon emissions. The latter are 3.5 billion people!

The solutions being promoted and promulgated should focus on those highly concentrated nodes: high energy-intensity groups, classes, countries, and regions. To peddle a blanket solution that assumingly will work everywhere in the world is to deny or refuse to accept the cultural, social, political, economic, geographic, topographic, and otherwise uniqueness and idiosyncrasies of a country.

illuminem Voices is a democratic space presenting the thoughts and opinions of leading Sustainability & Energy writers, their opinions do not necessarily represent those of illuminem.

Steven W. Pearce

Adaptation · Mitigation

illuminem briefings

Mitigation · Climate Change

David Carlin

Climate Change · Mitigation

Euronews

Mitigation · Climate Change

The Washington Post

Mitigation · Climate Change

Inside Climate News

Climate Change · Mitigation