Carbon Tax in Singapore: What you need to know

· 4 min read

As the Singaporean government is set to announce its revised carbon tax rate in the upcoming Budget 2022, oil firms have urged to maintain it at a level that would allow them to remain competitive, while Members of Parliament and activists alike have stressed the need to raise the rate and expand its scope. So, what exactly is a carbon tax and how does it work (or not)?

A carbon tax is applied to entities that produce carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases through their operations. The logic behind it lies on the economic principle of externalities: essentially, in evaluating the costs and benefits of an entity (like a factory or coal power plant)’s operations, the negative impacts they induce on society and/or the environment tend to get lost. The carbon tax, then, serves to monetise these external costs that were not counted and internalise them by making emitters pay for each unit of greenhouse gases they emit, so that they actually pay for the environmental, social and public impacts of their activities. Following this logic, the higher the tax rate, the higher the incentive is for emitters to change their behaviour — e.g. by reducing their emissions and transitioning away from fossil fuels — so they can minimise the amount they have to pay.

Singapore implemented its own carbon tax in 2019, becoming the first country in Southeast Asia to do so.

Under the Carbon Pricing Act (CPA), the Singaporean carbon tax is applied to industrial facilities that emit more than 25,000 tCO2e of greenhouse gases per year. Currently, there are around 40–50 taxable facilities who make up 80% of Singapore’s overall emissions.

Every year, these facilities buy “carbon credits” from the National Environmental Agency (NEA). Throughout the first phase of the carbon tax (2019–2023), they buy their annual credits at a price of $5 SGD per tonne. The facilities project the amount of GHGs they will emit for the year and purchase the credits accordingly — the credits, however, are not tradable among facilities nor can they use them for any other purposes. Facilities will be penalised if they end up emitting more than the amount of credits they had purchased.

Singapore’s carbon tax is not “ring-fenced”, which means that the revenues are not dedicated to a specific expenditure purpose. Instead, the revenue, which is expected to be around $1 billion SGD in the first five years, is consolidated by the government and allocated to different projects and schemes.

In particular, since the inception of the carbon tax, the government has increased funding for existing schemes such as the Resource Efficiency Grant for Energy and the Energy Efficiency Fund, in order to support improvements in energy efficiency in the industrial sector.

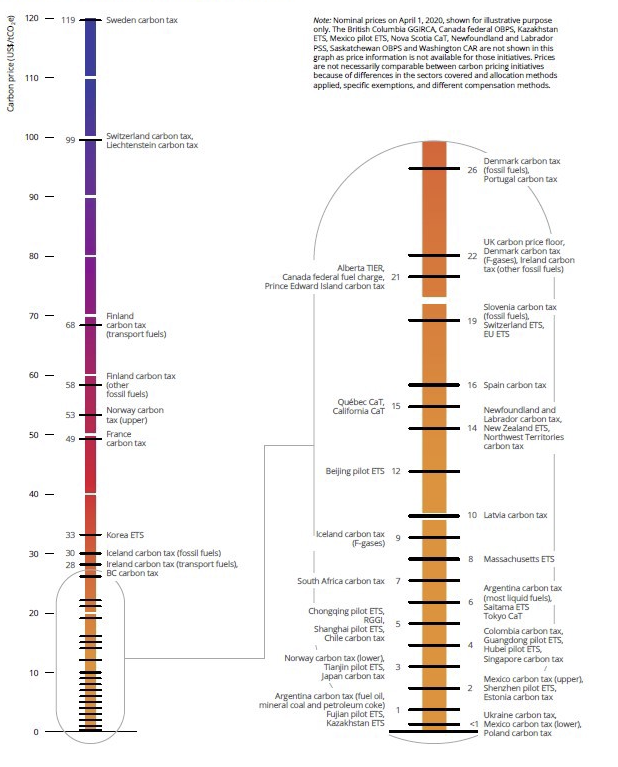

Compared to jurisdictions around the world that have implemented carbon pricing mechanisms, the current rate of $5 SGD per tonne falls on the lower end of the spectrum.

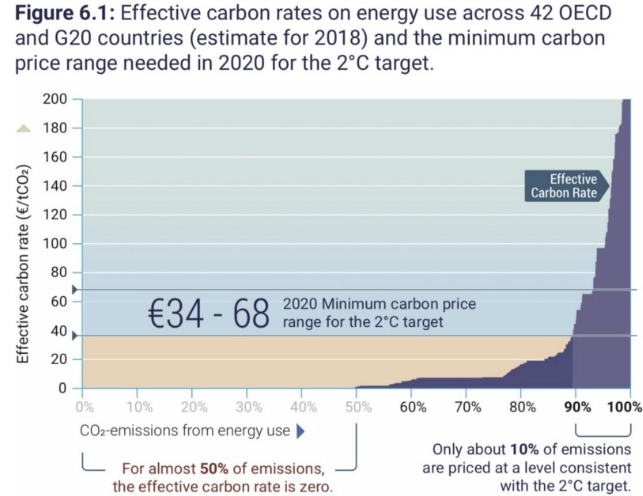

According to the United Nations Environmental Programme’s 2018 Emissions Gap Report, G20 and OECD countries need to price carbon by at least 34 Euros per tonne (roughly equivalent to $52 SGD, $38 USD) by 2020 in order to be effective enough to stay within the Paris Agreement target of limiting global warming to 2°C.

Next phase of Singapore’s carbon tax will start in 2024 and the government has already announced its plans to decide on the tax rate for this next phase in Budget 2022, so businesses have the time to plan and adjust accordingly.

As the government revises its carbon tax rate in Budget 2022, one question that needs to be reflected upon is the purpose of implementing this tax in the first place. If the rate is not raised to a level that makes it more cost-effective for emitters to switch to low-carbon alternatives and deliver actual emissions reductions, the carbon tax would be rendered just another source of government revenue.

Future Thought Leaders is a democratic space presenting the thoughts and opinions of rising Sustainability & Energy writers, their opinions do not necessarily represent those of illuminem.

Charlene Norman

Sustainable Business · Sustainable Finance

Giovanna Melandri

Ethical Governance · Environmental Sustainability

Lamé Verre

Corporate Social Responsibility · Social Responsibility

Associated Press

Climate Change · Environmental Sustainability

The Washington Post

Public Governance · Climate Change

The Wall Street Journal

Carbon Market · Corporate Governance