Building resilience to climate disasters: the rise of catastrophe bonds

· 10 min read

The increasing frequency and severity of extreme climate events and rising sea levels provide today's decision makers and investors with a unique opportunity to accelerate action and a resilient, green and sustainable future.Investing in disaster risk reduction is, in fact, not only a precondition for developing sustainably in a rapidly changing climate but it also makes good financial sense. Global investments of 1.8 trillion USD by 2030 in five selected areas - early warning systems, climate-resilient infrastructure, improved dryland agriculture crop production, global mangrove protection, and investments in making water resources more resilient – could generate up to 7.1 trillion USD of total net benefits (GCA, 2019). Nonetheless, domestic public finance earmarked for risk prevention as primary objective is often a very limited share of the national budget, suggesting governments are underinvesting in prevention and resilience in spite of being completely off-guard when the interconnected and cascading effects of such events hit.

A closer look at the global landscape of climate finance confirms that both public and private actors are not on the right track to mainstreaming disaster risk management into more comprehensive climate investment strategies. Overall, total climate finance has steadily increased over the last decade, reaching 632 billion USD between in 2019/2020. The vast majority (90.1%) flows towards activities for mitigation totalling 571 billion USD, while only 7.4% (about 46 billion USD) is allocated to finance adaptation actions (CPI, 2021). Although the persistent increase in the sensitivity of cooperation actors to the call for a balance of climate resources between mitigation and adaptation as set forth in the Paris Agreement, it is clear that further efforts must be made. To this aim, it is imperative that industrialized nations take into account country-driven strategies as well as the priorities and needs of less developed countries, especially those that are particularly vulnerable to the adverse effects of climate change and have significant capacity constraints, such as the Small Island Developing States (SIDs) and Least Developed Countries (LDCs) (Paris Agreement, 2015). Similarly, the Addis Ababa Action Agenda strongly encourages consideration of disaster risk and environmental resilience in development financing to ensure the sustainability of development results (Addis Agenda, 2015).

These provisions fully resonate with the strategy set out by the Sendai Framework 2015-2030, the global action plan to prevent and reduce disaster risk and achieve resilient and sustainable development. The Framework effectively ushered in the transition from "disaster management" to the current expanded interpretation of "disaster risk management", outlining four different priorities: (i) understanding disaster risk; (ii) strengthening disaster risk governance to manage disaster risk; (iii) investing in disaster reduction for resilience; and (iv) enhancing disaster preparedness for effective response, and to Build Back Better in recovery, rehabilitation and reconstruction. As it introduces the concept of multi-risk disaster management and stresses the need to strengthen the resilience of communities, it becomes increasingly important to elaborate a new and more coherent approach to climate change adaptation and disaster risk reduction, eventually promoting the alignment between the Paris Agreement and the Sendai Framework (OECD, 2020).

While it can be argued that disaster resilience is not prioritized because it is wrongly perceived as politically risky, seen as a cost for an event that might never happen within a political term, the adoption of disaster risk reduction plans and other similar strategic documents by a wide range of countries worldwide suggests the root cause of the problem must be sought somewhere else. In developing sustainable and climate finance, it is important to adequately integrate disaster risk reduction to reorient financial flows and financing, but this requires a mind-set shift in the financial system, moving from a short-term outlook to a long-range planning approach. While countries are stuck in a vicious circle where the financial cost of disasters is rapidly rising, limiting the ability of the public sector to mobilize and provide the necessary funds, current actions are clearly not commensurate with the magnitude of the challenge. To top it all off, the adoption of effective long term intervention strategies, including a sound climate risk management approach, turns out to be a very challenging exercise while trapped in emergency response.

Acknowledging the current limitation of public budgets and domestic banks’ lending capabilities, widespread misperception that disaster risk prevention is the sole responsibility of the public sector further aggravates the situation. To bridge the existing financial gap, it is therefore essential to promote the crowd-in of private sector entities and expand the investment base, capitalizing on their large untapped potential. The significant amount of capital they can provide and their extensive experience with innovative climate risk insurance products in developing and emerging economies, in fact, are key elements of a holistic strategy to improve the resilience of poor and vulnerable households against the impacts of climate change and natural disasters (InsuResilience Solutions Fund, 2020). However, due to the lack of coordination between the public and private sectors in blended finance operation and the limited maturity of the insurance market in developing countries, reaching out to institutional investors and channelling their financial resources into disaster risk prevention and management actions is not yet a tried-and-tested approach.

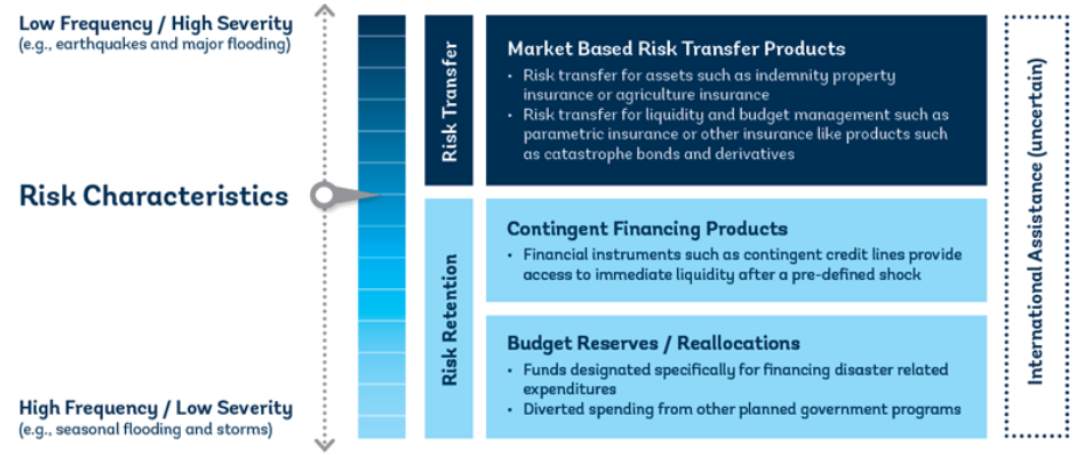

A range of insurance products can be used to mobilize private capital and address the financial risks of disasters, with the main criteria to be followed when selecting the product that suits the specific needs of a vulnerable country being the type of risks to which it is exposed and the frequency and severity of disaster events.

Figure 1 World Bank (2020). Disaster Risk Insurance Platform

When a country is predominantly exposed to Low frequency / High severity risks, which are those that do not occur often but may lead to profound consequences for the territory and the whole community, transferring the costs associated with the risk to a third party seems the best option to protect people and assets while boosting the financial resilience of governments. This is the case of small island states where named storms or violent earthquakes usually lead to major flooding and, in the worst cases, the loss of life, homes and infrastructure. In these contexts, such vulnerability is also exacerbated by many other issues small island states face and that compound their ability to bounce back from disasters, like their small geographic size, remoteness from trade partners and international markets, a lack of creditor trust and weak economic diversification. The costs of post-disaster reconstruction, in fact, can be exorbitant and is estimated to be equivalent, on average, to 2.1% of GDP every year in SIDS (WB, 2020).

A successful example of insurance securitization that allows to transfer a specific set of risks from an issuer or sponsor to capital market investors, is the catastrophe bond (also called “cat bonds”). First issued in the mid 1990’s, when the insurance and reinsurance industry began to look for alternative methods to hedge the risks associated with major catastrophe events capable of draining their market’s capital base, cat bonds are a type of insurance-linked security (ILS) through which investors take on the risks of a catastrophe loss or named peril event occurring in return for attractive rates of investment return. They offer, in fact, high-yield interest payments (usually between 4 and 5%) and have short maturities of one-to-five years. Low correlation as well as higher spreads and lower volatility than similar asset classes keep the market on trend for nearly 10% growth per annum since 2011, sparking hope that the cat bond market will reach 50 billion USD by the end of 2025 (Swiss Re, 2021).

Catastrophe bonds work similarly to insurance, paying out when a disaster event meets pre-defined criteria (e.g., a specified hurricane wind speed or earthquake magnitude), but also show considerable differences. Unlike conventional insurance products requiring the insurance provider to only make payments if and when a triggering event occurs, therefore exposing clients to its potential default, cat bonds are fully funded transactions involving upfront payments by the investors purchasing the bond, preventing the sponsor from the risk of a non-payment. They also allow clients to access a much larger pool of capital and, in general, longer coverage periods than conventional insurance.

In developing countries where the insurance market is not yet mature and public financial resources are not sufficient to cover the associated premium payment and transaction costs, the role of international financial institutions (IFIs) such as the World Bank is crucial to make the cat bond attractive to institutional investors. Leveraging its high credit rating, the World Bank lowers the perceived risk associated with the operation and increases investors’ confidence, ending up raising a sufficient amount of capital to cover a portion of the losses tied to a catastrophic event. From a client perspective, its mediation is also very important as it retains and manages any credit risk from market counterparties.

While the typical catastrophe bond structure sees the creation of a Special Purpose Vehicle (SPV), World Bank issued catastrophe bonds do not require an SPV. Instead, the client enters into an insurance or derivative contract with the World Bank which, in turn, issues the bonds, invests the proceeds, and transfers the premiums to the investors as periodic coupons on the bonds. If the pre-defined trigger event occurs during the term of the bond, all or part of the principal is transferred to the sponsor, leading to a full or partial loss for investors. If the bond expires without the trigger event occurring, the principal is returned to the investors. This transaction structure has been recently proposed by the World Bank under the “Capital at Risk” Notes program to provide the Government of Jamaica with 185 million USD insurance, as illustrated in the figure below:

Figure 2 World Bank (2021). Catastrophe Bond Transaction Structure / Case Study: Jamaica

With donor grants from the Global Risk Financing Facility (GRiF) and the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) used to finance cat bond premiums and transaction costs, Jamaica is the first small island state to independently sponsor a cat bond, in this particular case covering losses from tropical cyclone events potentially occurring between 2021 and 2023. This is also the first cat bond to use a cat-in-a grid parametric trigger design for tropical cyclone risk, including an innovative reporting feature: upon receipt of a notice issued by the Government of Jamaica, an independent agent makes a quick pay-out calculation based on the central pressure and track of the cyclone, without the need to assess real losses incurred by the country. Providing the fastest response possible to a climate disaster is, in fact, a prerequisite for successful recovery, rehabilitation and reconstruction. Thanks to the particular features of this transaction structure, the issuance attracted 21 investors from Europe (60%), North America (24%), Bermuda (15%) and Asia (1%), with most of them being ILS Funds, followed by insurers/reinsurers, asset managers and pension funds.

Climate change is driving increased risk across all countries, and the continuing series of disasters we are all witnessing show how unpredictable hazards can have devastating cascading impacts on all sectors, with long-lasting, debilitating socio-economic consequences. In a constantly changing climate, the cost-benefits of investing in prevention, disaster risk reduction and climate change adaptation have never been clearer, or more urgent. However, there remains a huge financial gap that needs to be filled immediately as it will widen even further due the increasing frequency and severity of extreme climate events. Strengthening existing prevention and response systems while identifying strategies to make investments in disaster risk reduction less risky require the mobilization and combination of a significant volume of public and private financial resources.

IFIs and multilateral institutions are the cornerstone of such operations because of the support they provide to the creation of catalytic mechanisms in developing contexts. If, on the one hand, their extensive experience and credibility build the confidence of the public sector by ensuring transparency and integrity, on the other hand the great availability of financial resources and their high credit ratings help create investment opportunities of commercial value with an attractive risk-return profile, meeting the investment needs of institutional investors. While catastrophe bonds are just one of many financial instruments allowing public and private entities with different objectives to invest alongside each other while achieving their own objectives (whether development impact, financial return or a blend of both), they are among the very few ones capable of covering the exorbitant costs of climate disasters, eventually promoting the resilience of both communities and financial systems.

Energy Voices is a democratic space presenting the thoughts and opinions of leading Energy & Sustainability writers, their opinions do not necessarily represent those of illuminem.

John Leo Algo

Ethical Governance · Environmental Sustainability

Steven W. Pearce

Adaptation · Mitigation

illuminem briefings

Carbon · Environmental Sustainability

Politico

Climate Change · Agriculture

UN News

Effects · Climate Change

Financial Times

Carbon Market · Public Governance