Bringing Equity to Carbon Markets

· 7 min read

Carbon credit projects in Madagascar promised to protect mangroves and sustain the local communities’ livelihood. However, after the government decided to nationalize carbon rights, the 10 villages involved were left without profits. This illustrates a worrying development: sometimes the voluntary carbon market (VCM), despite its intentions and evolving best practices, negatively impacts Indigenous peoples and local communities.

High-quality carbon credits can play a crucial role in accelerating decarbonization outside of a company’s value chain. Specifically, carbon credits represent an important financing mechanism to protect, manage, or restore natural ecosystems while providing a unique opportunity for development and livelihood generation in the Global South. However, while some carbon projects have supported local job creation and education, in other cases, carbon credit generation has resulted in failure by driving people from their homes.

Drawing on an established equity framework agreed on at the Convention on Biological Diversity COP14, we have identified three principles to further promote alignment between the rights of communities and the VCM and deliver trust: recognition, participation, and transparency. This article explains what will need to happen along the way, and what role RMI will play in this transition.

Assuring equity in the processes and outcomes of the voluntary carbon market is first and foremost a matter of rights and governance. “Equity” recognizes inequalities and implies that those facing harsher conditions should receive more support and resources to compensate. In the context of the VCM, equity means ensuring that the processes and outcomes of carbon credit generation, verification, and trade do not disadvantage the communities involved, but rather sustain and promote their livelihood. The people involved in these projects often belong to Indigenous or local communities, usually referred to as IPLCs.

Globally, 370-420 million people self-identify as Indigenous — from ethnic groups who are descended from and identify with the original inhabitants of a given region. Local communities traditionally hold lands and resources collectively under customary and statutory tenure, but do not self-identify as Indigenous. For them, the legitimacy and rights over resources are based on traditional use and shared common-property arrangements. Smallholder farmers — small farmers who may or may not own the land they farm — also play an important role in mitigation activities. In the Global South, smallholder farmers represent two-thirds of the rural population, but face tree and land rights recognition issues.

Despite de facto owning at least half of the lands and forests targeted by climate change mitigation pledges and restoration activities, less than 20 percent of those are formally recognized as owned by or designated for IPLCs. This fits into the larger context of the voluntary carbon market grappling with issues of good governance, trust, transparency, quality, and scarcity. The lack of transparency is at the root of informational and power asymmetries that can leave IPLCs vulnerable.

With restricted yet heterogeneous supply and limited number of buyers, the VCM is an illiquid market. Like other illiquid markets, price discovery, especially for co-benefits, is challenging, exchange is inefficient, and skepticism is high. With high-volume buyers having such high power, carbon credits end up being underpriced, with prices around $3 per ton. As credits travel down the supply chain from developers to validation and verification, to brokers all the way to buyers, all parties take rent from the already low price. In the absence of regulation, counterparties are generally not creditworthy. In some instances, national and jurisdictional plans can also prevail over community interest. All of the above strips vulnerable communities, especially smallholders, of their rights and any benefits they should receive.

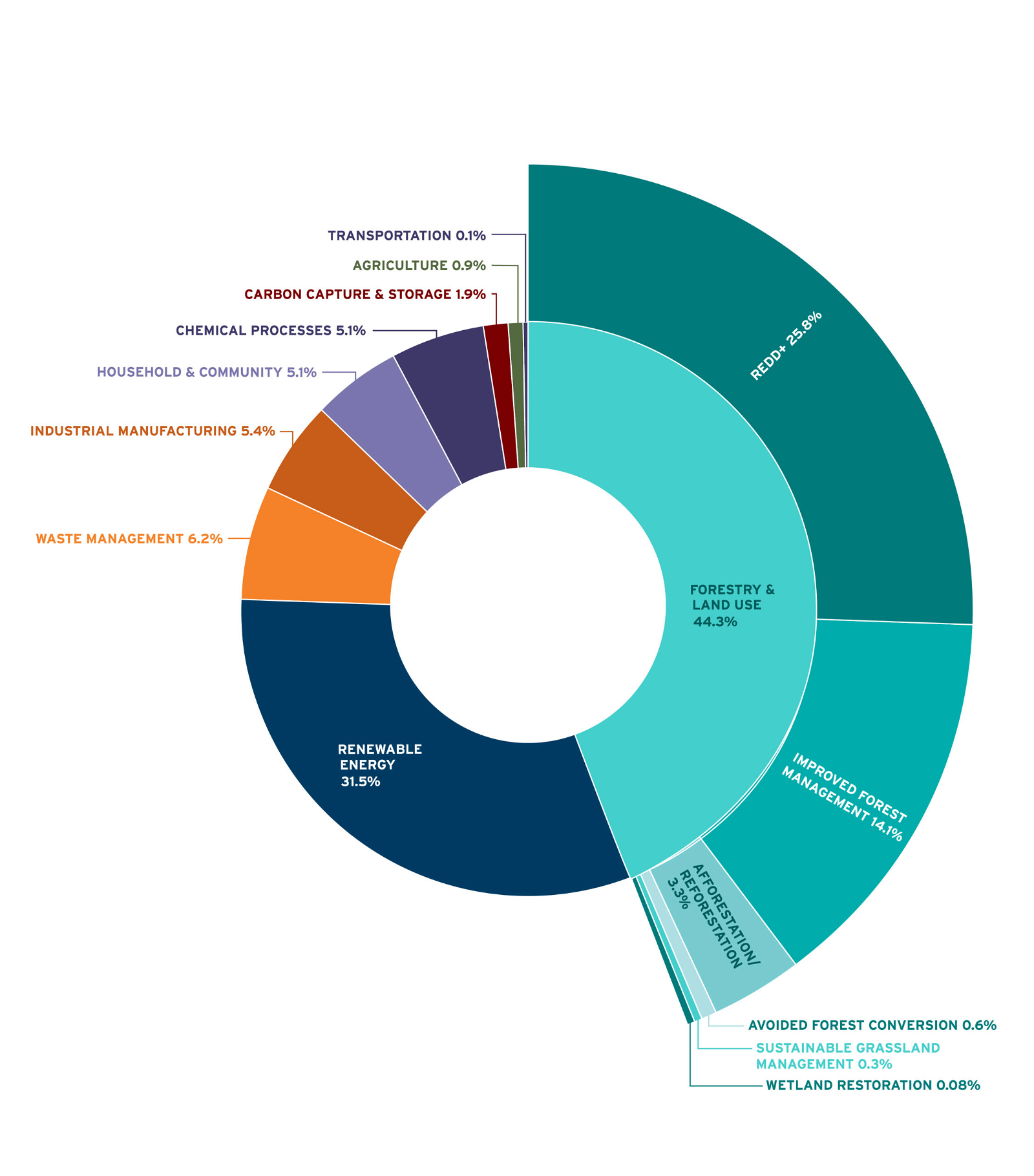

Forestry and land use credits have attracted scrutiny for adversely impacting IPLCs. Because of the land tenure rights involved and the related land-grabbing incentives, these credits are the most prone to situations where land rights of Indigenous peoples and local communities are not recognized. Forestry and land use credits represent over 40 percent of total issuance by the four main registries, 33 percent of all issuances in North America, and 66 percent of all issuances in the Global South regions. IPLCs very effectively manage 80 percent of global biodiversity and over one third of global intact forests. But without the necessary safeguards in place, IPLCs are disproportionately vulnerable to unsuccessful carbon credit projects, particularly in the Global South.

The following non-exhaustive principles illustrate a path toward a more trusted and equitable VCM:

Land titling in and of itself is not a silver bullet remedy, but both at the project and jurisdictional level, land tenure rights of IPLCs should be explicitly recognized and secured. This begins with recognizing land rights and is followed by assisting Indigenous peoples and local communities in their capacity to describe, price, and trade credits. Independent legal counsel and grievance redress mechanisms for IPLCs could greatly support this effort.

Equitable projects should engage IPLCs though inclusive project-design and robust distribution of both monetary and nonmonetary benefits, like cash payments, tenure security, and ecosystem protection. Although indicated as a relatively weak model on the spectrum of forest tenure reform, benefit agreements that provide upfront capital can facilitate early-stage buy-in, cover project start-up costs, and mitigate risks to communities. Similarly, international carbon funds, sovereign wealth funds, and donation funds can align their investments with equity and justice priorities to advance projects that benefit IPLCs.

To ensure participation throughout project design, project developers should respect and advance the Free, Prior, and Informed Consent (FPIC) right, recognized in the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples. The FPIC empowers people to negotiate the conditions for project design, implementation, monitoring, and evaluation. By leveling information and power asymmetries, FPIC is a powerful tool to ensure that community-led climate action is delivered.

Credit and transactional transparency have the potential to remove roadblocks to equity in the VCM. Both credit and transaction data (e.g., their counterparties and prices) need to be transparent. Collecting and disclosing data, including equity outcomes, shouldn’t simply be a performative exercise but should support market participants in making informed decisions. The data needs to be verifiable and audited, and redress processes need to be in place should any local communities or third parties identify data that is not reflecting the reality on the ground.

Carbon needs to be sold as a time-bound service, not as an asset: sequestration should be sold, while the title of the land stays with its owner. Contract structures can support trust and protect IPLCs from future price increases that benefit buyers only. Capital markets can serve equity as well, but only if properly regulated and if carbon-based securities are not separated from their underlying assets. Market regulators are catching up. Without oversight, the market is prone to litigation. Access to the market should be limited to good faith sellers and buyers that refrain from predatory behaviors.

Data and technology can be leveraged to achieve transparency and increase trust. For example, remote sensing and advancements in forest modeling can help demonstrate impact through real-time and verifiable data on carbon and biodiversity. Blockchain holds the promise to connect players across a credit supply chain, integrate technologies and data, enable traceability, and lower barriers to entry. Blockchain can also keep a credit tied to its validating stream of monitoring, reporting, and validation data, which would support price discovery over time.

Transferring these principles from paper to practice will not be achieved if we don’t first create the appropriate market infrastructure. Urgent climate action needs a purpose-driven VCM designed to serve people and the planet alike, relying on improved visibility through data, strong monitoring and evaluation, and a leveled field to engage Indigenous peoples and local communities.

This article is also published on RMI. Future Thought Leaders is a democratic space presenting the thoughts and opinions of rising Sustainability & Energy writers, their opinions do not necessarily represent those of illuminem.

Jesse Scott

Carbon Market · Carbon Regulations

illuminem briefings

Carbon Market · Corporate Sustainability

illuminem briefings

Carbon Regulations · Carbon Market

The Wall Street Journal

Carbon Market · Corporate Governance

Trellis

Carbon Market · Carbon

Eurasia Review

Carbon Market · Carbon