· 17 min read

Let me start with a big claim. Product development is making the world shittier.

Woah! Hold up, you say. Where’s all this coming from? I thought the sprinting, scrumming, huddling and cuddling was doing good?

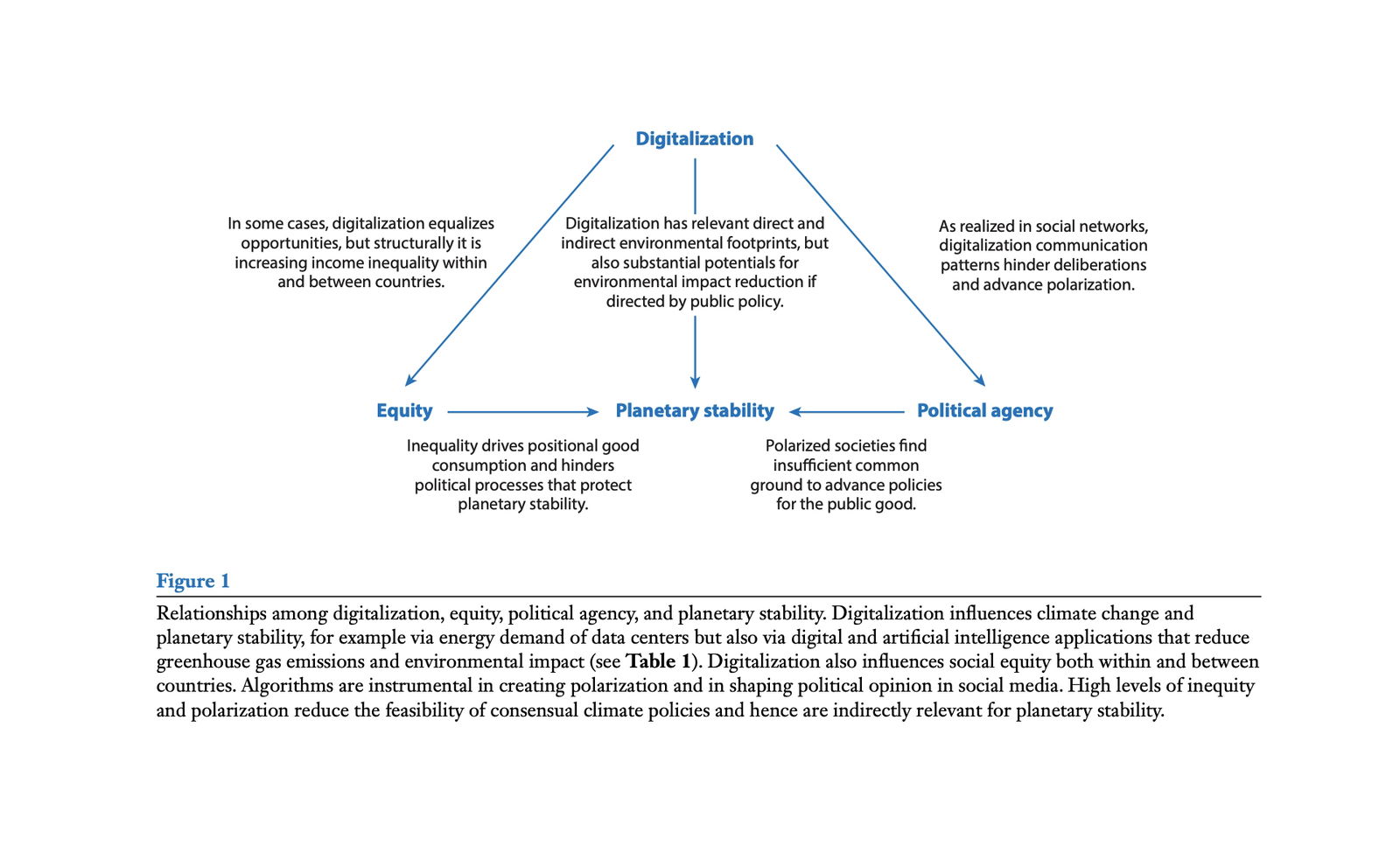

Let me qualify my big claim by putting things a little more formally, as highlighted by Creutzig et al. in a brilliant paper (opens as PDF) last year: Digitalization has historically increased environmental impacts at local and planetary scales, affecting labour markets, resource use, governance, and power relationships.

In other words, instead of our digital products “making the world a better place”, as is so often the cliché claim, they seem to be making things worse.

Taken within the broader systems context, as is necessary for any analysis of this kind, the processes we execute to ‘digitalise the world’ have resulted in planetary instability (yes, framed in the present as this is very real right here, right now).

The gist is that, unless we find ways for digitalisation to enhance democracy, political agency and equity, all whilst massively decreasing resource extraction, production and consumption, things are looking very sad. Very sad indeed.

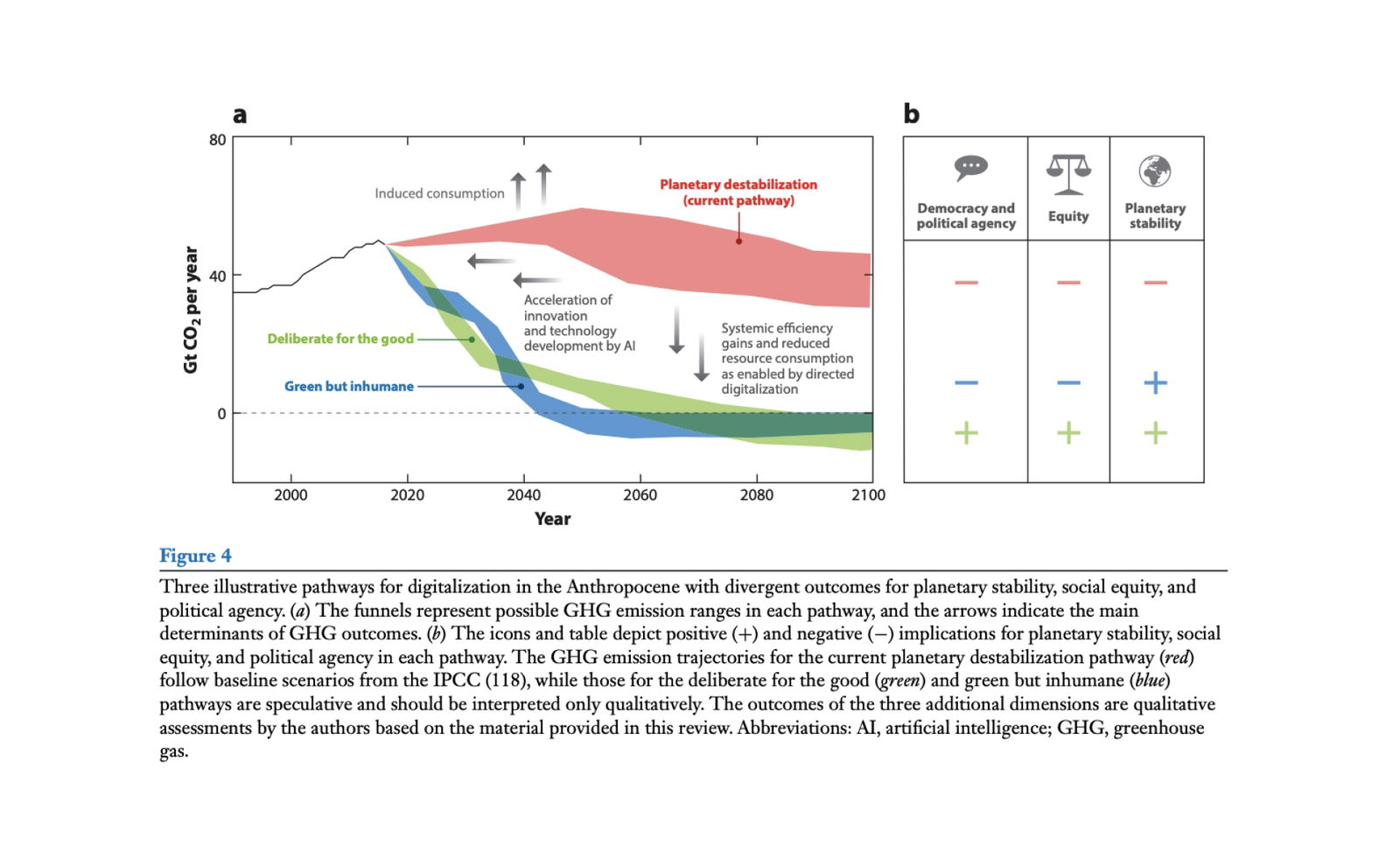

Now, I cannot possibly get into all of the broader systems dynamics today. Instead, what I can do is highlight the limitations of the current product development paradigm. From that basis, I can propose a different set of ‘initial conditions’ from which a new paradigm for responsible, ecologically literate product development can emerge. In doing this, I will argue that product development and product development teams might be able to ‘net positively’ contribute to the ‘Deliberate for the good’ pathway you see in the visual above.

Let’s get stuck in by first taking you back a couple of decades.

The birth of the Agile Manifesto

It’s the middle of winter. The ‘Snowbird 17’ – Kent Beck, James Grenning, Robert C. Martin, Mike Beedle, Jim Highsmith, Steve Mellor, Arie van Bennekum, Andrew Hunt, Ken Schwaber, Alistair Cockburn, Ron Jeffries, Jeff Sutherland, Ward Cunningham, Jon Kern, Dave Thomas, Martin Fowler, and Brian Marick – gather against the breathtaking backdrop of the Wasatch Mountains in Utah, USA.

*I imagine there’s plenty of whiskey, Cuban cigars, and of course, the unmistakable smell of rich mahogany.

Although views differ about pathways forward, there’s a shared frustration that grounds the collaborative process. Some shit’s gotta change…

Epic montage. Fast forward. New scene. 3, 2, 1…

68 words later and we have what many consider a paradigm-shifting contribution to the process of software (which, of course, has broader implications, impacting organisational structures and many other things) development.

Manifesto for Agile Software Development

We are uncovering better ways of developing software by doing it and helping others do it.

Through this work we have come to value:

Individuals and interactions over processes and tools

Working software over comprehensive documentation

Customer collaboration over contract negotiation

Responding to change over following a plan

That is, while there is value in the items on the right, we value the items on the left more.

This short manifesto was supported by 12 guiding principles.

For me, everyone on our team, and likely most folks reading this, the work these 17 chaps did has fundamentally and very directly impacted how we’ve spent thousands of hours of our lives. Each, not collectively!

Various interpretations of this work have emerged. We’ve all heard the claim, “We’re doing agile!” even when this couldn’t be further from the truth. Some folks hate it. Others love it. Context most certainly matters.

Regardless, and acknowledging what I’ve already claimed in the introduction, there is power to this contribution. Much of the spirit this group attempted to embody has well and truly endured. It was, in so many ways, solid progress.

But, and I hope you’re already onto this, note all that the manifesto doesn’t cover. Here are the 12 principles to refresh your memory:

- Our highest priority is to satisfy the customer through early and continuous delivery of valuable software.

- Welcome changing requirements, even late in development. Agile processes harness change for the customer’s competitive advantage.

- Deliver working software frequently, from a couple of weeks to a couple of months, with a preference for the shorter timescale.

- Business people and developers must work together daily throughout the project.

- Build projects around motivated individuals. Give them the environment and support they need, and trust them to get the job done.

- The most efficient and effective method of conveying information to and within a development team is face-to-face conversation.

- Working software is the primary measure of progress.

- Agile processes promote sustainable development. The sponsors, developers, and users should be able to maintain a constant pace indefinitely.

- Continuous attention to technical excellence and good design enhances agility.

- Simplicity–the art of maximizing the amount of work not done–is essential.

- The best architectures, requirements, and designs emerge from self-organizing teams.

- At regular intervals, the team reflects on how to become more effective, then tunes and adjusts its behavior accordingly.

What do you reckon?

I’ll start by saying that the Agile Manifesto is a fairly narrow value system. Like much of the socio-cultural/economic/political system within which this manifesto emerged, there’s a narrow outcome orientation, plenty of ‘externalisation’, seriously limited diversity in terms of the inputs into this process, and somewhat of a disconnect relative to the broader system dynamics1.

The products we develop are imbued with diverse values. Some of these values are explicit and intentional. Others are implicit and unintentional.

Taken together, these values impact what we design. What we design impacts how technology is used. Our use shapes who we are, individually and collectively.

The Snowbird 17 really missed this. They seem to have been almost exclusively interested in building ‘good’ software, with good meaning something very limited relative to its potential.

This, at least in hindsight (but perhaps with a more diverse and representative approach to the development of the manifesto, which may have included practitioners across disciplines, people from different cultures, a broader socioeconomic representation, etc. could have been proactively avoided), has been an ecological failure.

Responsible product development ought to be systems literate. Here I refer to systems – an interconnected set of elements that is coherently organised in a way that achieves something (function or purpose) – in the broader sense of the meaning, perhaps best aligned to Donella Meadow’s work. It ought to deeply and explicitly value ecology. It ought to occur within an environment of care, directly considering the contribution the process and its various outcomes have on people's – everyone from the team developing the product through to those who may use or be impacted by it – Happy CAMPER2 status. In the language of Creuztig et al. above, it ought to contribute, by design, to ‘Deliberate for the good’.

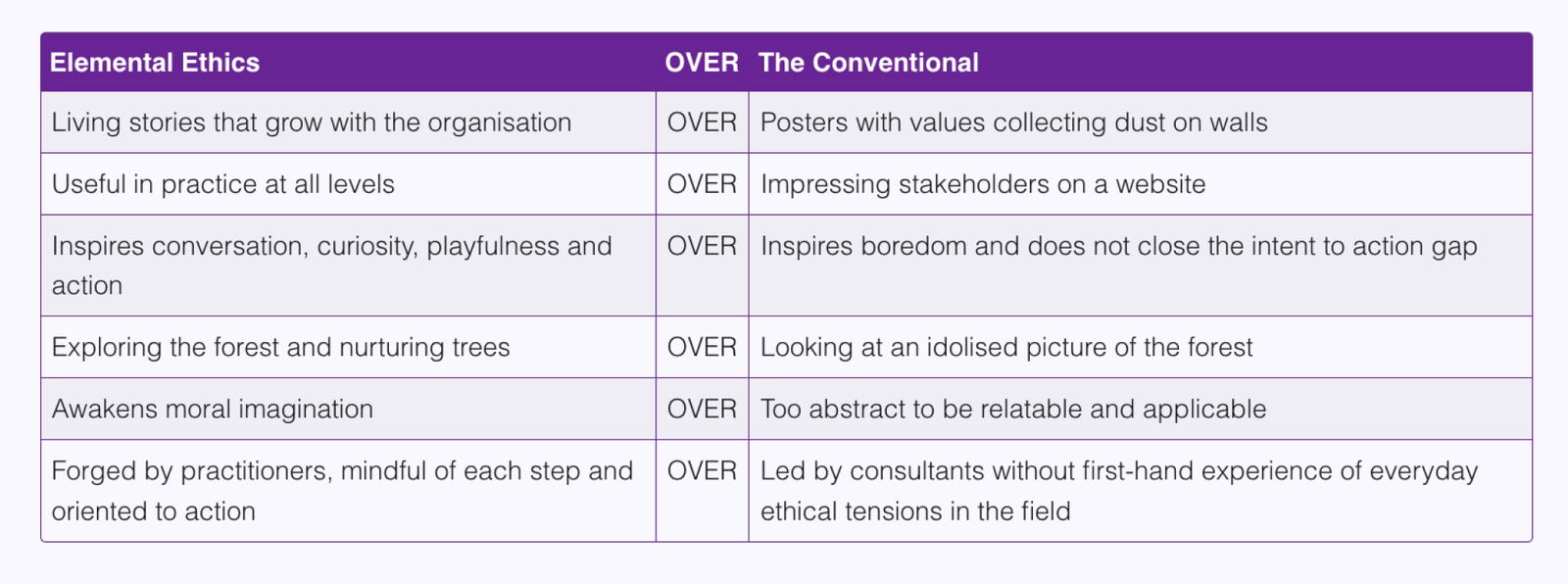

Many have tried to capture a somewhat broader orientation to digital product development over the years, with approaches ranging from Value Sensitive Design to Ontological Design through to Axiological Design. We have a whole movement in Sustainable Web Development (of course, with its own manifesto). We’ve got plenty of folks trying to integrate value systems and ethics into Design Thinking.

Each of these, and many of those I haven’t mentioned, have their merits. All seem to have been developed by smart and caring teams, as far as I can tell. But… I’m also arguing today that they each have certain drawbacks. Namely, for various reasons, they are hard to operationalise and embody.

Many of these approaches have been developed within academia. This can often lead to a disconnect between the ‘idealised state’ or set of conditions, and the everyday realities of cross-functional teams. Other approaches simply exist outside the product context. They seek to impose new things, ask folks to do new work, require plenty of new knowledge and, as a result of this and more, fail to convert certain ethical intentions into verifiable ethical action.

There’s too little focus on an embodied, integrated and embedded approach.

The ethical intent to action gap: a problem worth solving

So let’s break this down.

Traditional approaches to ethics are top-down.

The inputs to such processes tend to be highly constrained and rarely reflect the diverse needs, interests, and desires of those expected to act upon said approaches. Nor do they reflect the diverse needs, interests, and desires of the folks that will be impacted by the work these approaches inform.

They refer to formal concepts that very few people are able to directly interpret and meaningfully act upon (do you know the difference between a categorical and hypothetical imperative?).

They don’t reflect the everyday realities of cross-functional product development teams.

They exist as add-ons. They’re outside everyday workflows, rather than integrated and embedded. Ethics – the practical process of assessing options relative to your purpose, values, and principles so that you can do more of what you believe to be good and right – isn’t part of agile. Not even close.

They’re not something we live and breathe. They don’t really feel a part of us. They’re disembodied. Posters on the wall and all that.

They have contributed – as part of the wider system context within which they exist – to a big gap between what is said and what is done.

This gap between what is said and done plays a huge role in the reality that ‘Digitalization has historically increased environmental impacts at local and planetary scales, affecting labour markets, resource use, governance, and power relationships.’

This – the gap between ethical intent and action – is a problem worth solving. Arguably in itself, but more importantly because of the positive impact on political agency, equity and planetary stability.

People care deeply about this problem and opportunity. It’s important. Really important. In fact, it’s one of the biggest reasons people show up to work. However, current approaches are undeserving of the entire market. Current approaches make it way too hard to close the gap. This remains the case even though there are more people than ever before working to address it (read: Tech Ethics, AI Ethics etc. has blown up as a field).

Also, solving it isn’t only nice to have, it is bloody necessary. Our work needs to help build a better world, not a shittier one. We need to get ourselves onto the ‘Deliberate for the good’ pathway.

After more than a decade apiece, we’ve fallen in love with this specific problem. We’ve long asked questions like:

- How might we close the ethical intent-to-action gap?

- What organisational conditions are necessary?

- What embodied knowledge is required?

- What tools, workflows, rituals and behaviours need to emerge?

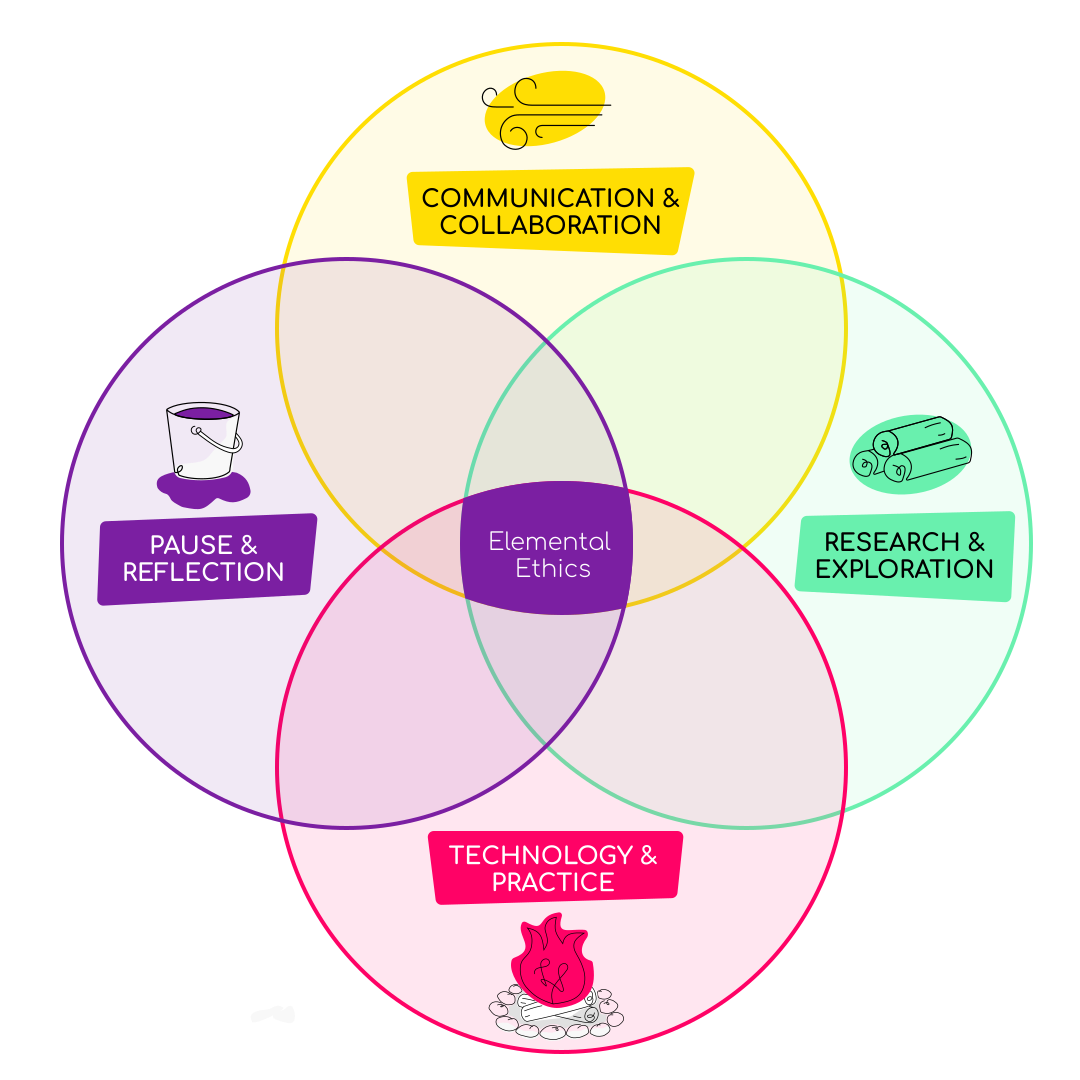

Our answer, framed simply for the purposes of this post, is Elemental Ethics™.

Elemental Ethics: Empowering teams to do more good

At first, we referred to Elemental Ethics as a ‘new type of ethics framework’, something that integrates into existing tools, rituals, and workflows. But we haven’t felt satisfied with how this is framed.

So what is it?

My colleague Mat, during a typically wide-ranging discussion of back-and-forth inquiry, suggested that “Elemental Ethics™ is what Elemental Ethics™ does”.

I sadly disclose that Mat did not say “™”… I know, I was as disappointed as you.

So, how does Elemental Ethics help product development teams embark on the ‘Deliberate for the good’ path?

- Like a breath of fresh air, it invites teams to open communication flows and build shared meaning and understanding, whilst surfacing the necessary tensions that help teams develop healthier ways of working together.

- It grounds teams to the earth they stand on, supporting the research and exploration that clarifies how to approach doing the ‘right’ things the right way.

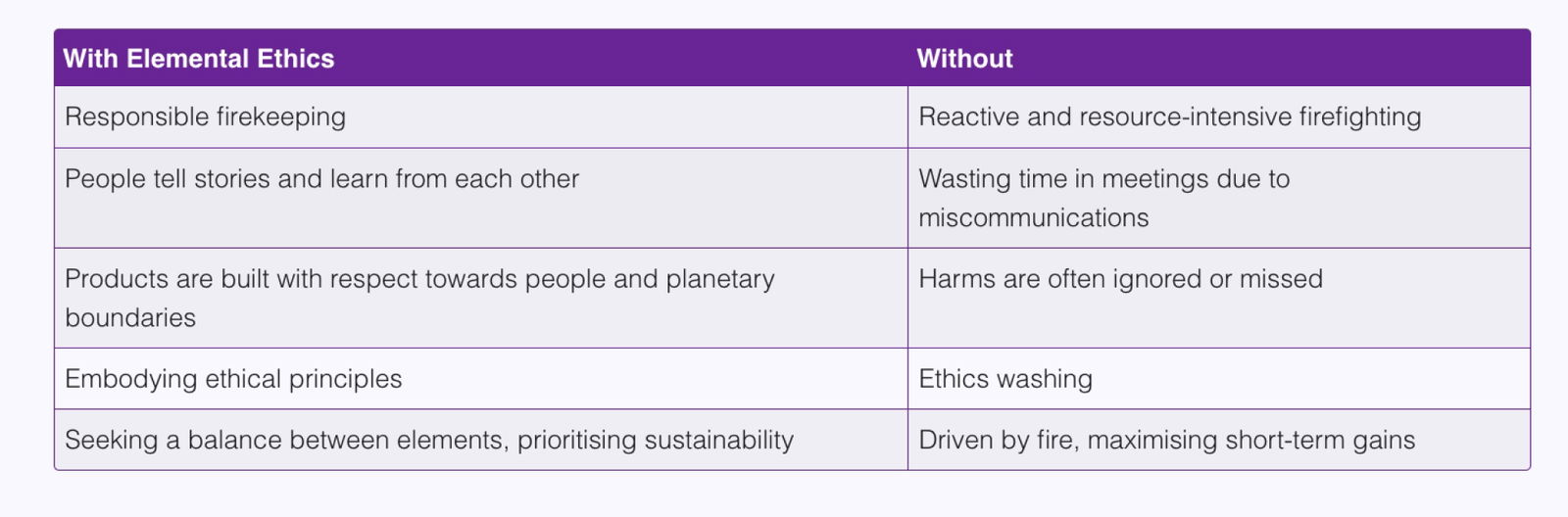

- It empowers teams to shift from incessant firefighting to responsible firekeeping, delivering fire‘s light and warmth, whilst reducing stray wildfires that endanger people and the planet.

- It reminds teams to pause and reflect on the meaning and purpose of their work by reflecting their values in the water that keeps us hydrated, and, if needed, uses that same water to extinguish the wildfires that get out of hand.

Each of these areas has associated skills in action. Something my colleague, Mat (yes, the famous Hip Hop artist from AI Inside), will post about over the coming days.

Importantly, Elemental Ethics is not values neutral (no human institution is). We operate based on assumptions, beliefs and embodied motivations. One of these things we believe is that any framework or model should attempt to uncover and explicitly communicate the deeper beliefs guiding its development upfront. The Agile Manifesto doesn’t do this. Nor do most comparable approaches.

So here are a few of the big assumptions and beliefs guiding our work:

- Humanity, technology, and nature are one interconnected and interdependent living system, all operating within a finite biosphere.

- To effectively close the ethical intent to action gap, new ways of thinking, feeling, doing and being must be embedded into existing tools, workflows, and rituals.

- Ethics is often seen as boring and burdensome, likened to compliance, something that ‘disables innovation’. It is, can, and should be so much more. We are making ethics more interesting, relatable and practical through the use of a nature-inspired language system called SMILES. As a result, an integrated, embedded and embodied approach to ethics actually enables innovation.

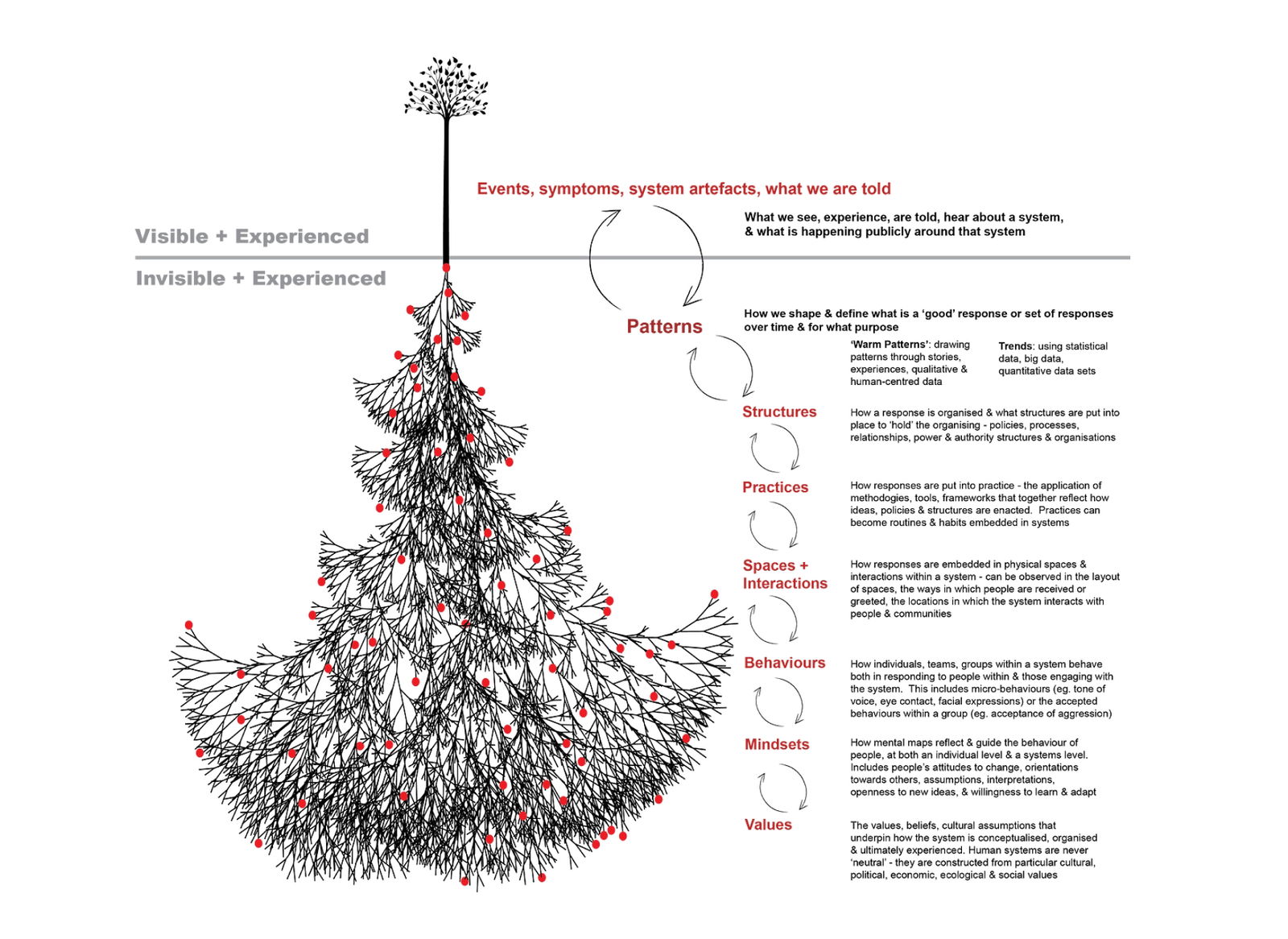

- Teams developing products exist with broader organising structures. These organisations exist within economies. These economies exist within broader structures, stories, values and belief systems. All of these human institutions exist within the biosphere. We are systems tinkerers. We seek to ‘operate’ at basically every level of the system – as seen in the visual from Griffith University’s Centre for Systems Innovation below – in our attempt to bring about positive change and support the ‘Deliberate for the good’ pathway

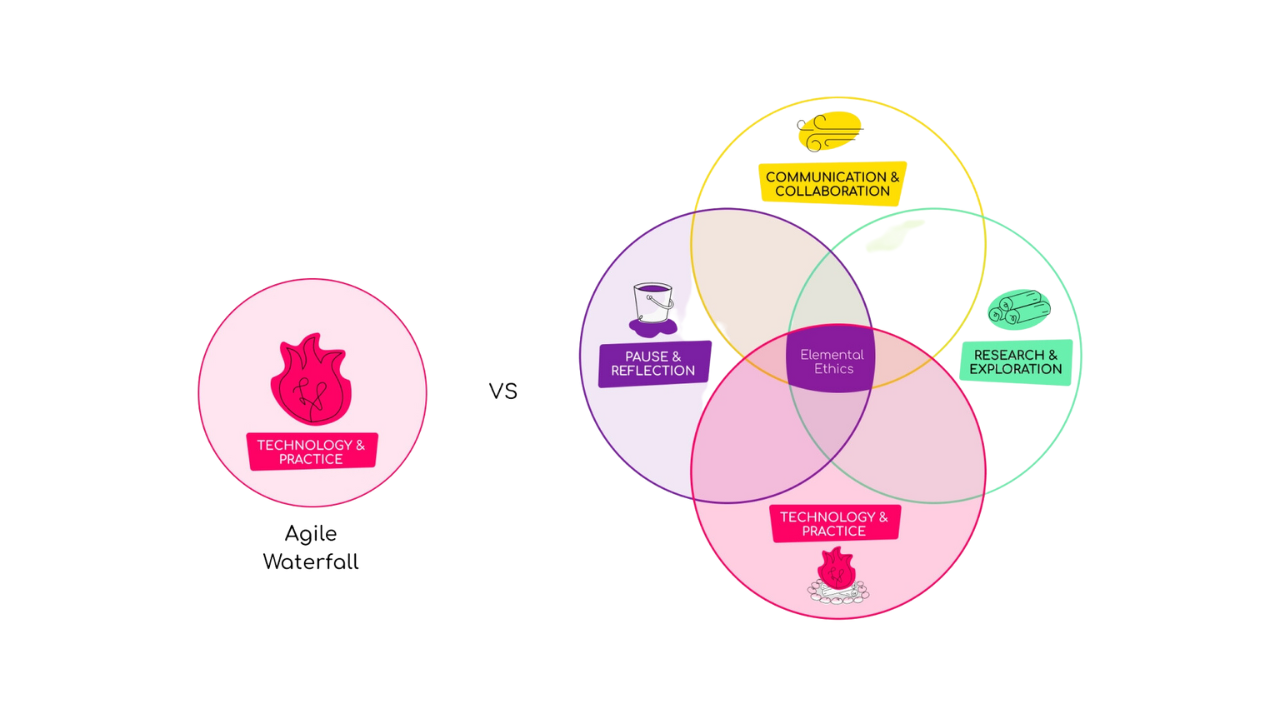

In this way, Elemental Ethics™ is more like a new paradigm (shared mental model) for responsible, ecologically oriented product development. It still values much of what the Snowbird 17 captured in the 4 values and 12 principles of the Agile Manifesto (I mean, it’s hard to argue that comprehensive documentation matters more than a working product…). But, I’m proud to suggest the possibility that it takes this much, much further.

Elemental Ethics: From agile firefighting to responsible firekeeping

Now that you’ve been introduced to aspects of our nature-inspired language system, let’s compare Elemental Ethics™ to the principles from the Agile Manifesto and the way we practice agile using our framing that technology is fire.

Agile is a fire-focused practice. Its goal is to start new fires – products – and keep the fire burning as hot as it can. By being hyper-focused on the fire practice, it often fails to acknowledge the wider context. How is the fire affecting people? Is the wind carrying sparks into surrounding vegetation and starting wildfires? Have the practices that developed the fire eroded the microbial diversity within the soil? How is this impacting the broader ecosystem? Is there enough water available to temper the flames that burn too bright? You get the gist.

As long as the fire is burning in the form of ‘working software’ that ‘satisfies business needs’, the spirit of agile is content.

What agile fails to acknowledge is that other elements – air, earth and water – are crucial for building, maintaining, and, where necessary, extinguishing fire.

Because of this shortsightedness, we keep practising agile software development by inventing fire rituals, such as standups and retrospectives, that feel deeply unsatisfactory. Instead of working with the winds, we keep blowing on the fire and then wonder why we get a face full of smoke. We’re puzzled by the wildfires that keep starting around us. This keeps us busy with firefighting when we should be minding a fire that serves a specific purpose.

The Agile Manifesto was essentially a manual for building strong fires that meet business needs. But, as I hope to have now made clear, it failed to acknowledge the importance of practising fire safety by working with the other elements.

This is where Elemental Ethics enters the picture as a responsible firekeeping practice. It goes beyond fire-starting software development methodologies like agile – and waterfall! – and brings attention to everything else we need to start and maintain a healthy fire. To truly make the world a better place, we need a more balanced product development practice that acknowledges the responsibility we have towards each other and the planet.

While the Agile Manifesto principles do emphasise the importance of collaboration, having face-to-face conversations and empowering self-organising teams – all ‘good’ things – agile keeps its gaze fixed firmly on the flames of its own fire. It struggles to seek diverse perspectives beyond what we might consider direct customer needs. It ignores the impact of digitalisation on equity, political agency and planetary stability. It basically externalises everything that doesn’t ‘pay the bills’.

Similarly, reflection exists in service of how the team can become a more efficient code-delivering machine. It’s not actually about how to ‘do good’ in the world. Agile – as a constrained value system – doesn’t want you to reflect on whether the world even needs the products you’re building. By needs here I really mean that the product or service enhances people’s capacity to live healthy and dignified lives, within the constraints of the biosphere. For agile itself, the ‘answer’ is more working software, delivered faster.

In contrast, Elemental Ethics is systems-oriented by design. It innately considers the context of where the fire is being built. It leads with what matters to humans and earth systems, rather than just ‘bringing this into’ product development as some afterthought. Its higher-order goal is building and maintaining fires that foster, and equitably distribute, just the right amount of warmth and power to those around the campfire:

| Agile firefighting | Responsible firekeeping with Elemental Ethics | |

| Air | Taking a powerful leaf blower to the fire (lots of air!), whilst ignoring stronger winds and their directions | Meaningfully collaborating to work with surrounding winds and ensure good ventilation |

| Earth | Not considering the clearing in which you’re building a fire – or not even bothering to make a clearing in the first place – and starting a fire in the middle of the forest with whatever burns the fastest | Mindfully selecting the best location for your campfire by paying deeply knowing your surrounding, gathering different types of sustainable fuel, and practising leave no trace principles that create conditions for genuine regeneration when you’re done |

| Fire | Focus on keeping the fire going, whatever it takes | Maintaining a warm fire, ensuring it doesn’t spread out or die out |

| Water | Not paying attention to inevitable stray fires until they grow too large to ignore | Proactively filling buckets of water and putting out stray fires before they grow too large to extinguish |

| Goal | Build the best fire we can as fast as we can | Build a healthy and balanced fire that can sustain us through cold, dark nights |

Why shift? The case for Elemental Ethics

All that I’m saying here has the potential to lead to profound organisational shifts. Elemental Ethics operates at the level of culture, starting with values and mindsets. From there it influences behaviours, spaces and interactions, practices, structures and patterns. The system artifacts produced, and the events experienced as a result, are manifestations of the closing ethical intent to action gap.

All of this is diverse, inclusive and embodied. It’s a way of being and doing that feels more natural, relatable and rewarding.

It’s not quite magic, but…

Going on the journey together

Okay, I’ve taken you on a journey. But why believe anything I’m saying?

I fully endorse the deep scepticism you may currently feel. With that said, I am willing to bet that you know, ‘deep in your bones’, that something is wrong today. The tension between how you’d like to contribute, and what you know you are contributing, is undeniable. You know that the preponderance of empirical evidence suggests we’re in a precarious position. You know there’s an urgency to this. You know that a lot of our product development practice is disembodied. You literally feel this, or rather, you don’t. You know that it serves ‘business needs’ (whatever they actually are…) above pretty much all else. You know that our work could be so much better if we were just willing to question our deepest assumptions about what is, who we are, and what we have the potential to be.

So, I invite you to take a step back. In fact, make it a big one. Now ask yourself, is technology really realising its full potential? Are we equitably distributing its benefits? Are we solving the right problems the right way? Are we, as a species, embodying oneness with the rest of the ‘natural world’? Are we operating in recognition of the radical responsibility we uniquely have as the only custodial species on this planet?

If all this leads to the realisation that the incessant firefighting needs to come to an end, let’s talk.

This article is also published on Tethix. illuminem Voices is a democratic space presenting the thoughts and opinions of leading Sustainability & Energy writers, their opinions do not necessarily represent those of illuminem.