Batteries, biofuels and shareholder resolutions

· 5 min read

I’m just back from three weeks’ holiday in Canada – a country with beautiful natural resources (being home to nearly 10% of the world’s forests) and well-aware of the challenges of using them sustainably. I was captivated by the natural beauty of the Pacific Rim, where nature’s power is on full display, showcasing the importance of preserving our environment. It was wonderful to simply walk and enjoy the great landscapes (no issues with bears!).

But it’s back to work now and we look at three different questions in this edition of the newsletter.

One of the key challenges of the transition to clean energy is the intermittent nature of renewable energy sources like wind and solar. This means that some form of energy storage is essential, with electric batteries being one (but not the only) way of doing this. According to McKinsey, the global requirement for battery storage is projected to increase from 700 GWh in 2022 to around 4,700 GWh by 2030 [1], implying a need for 120-150 new battery factories. Accompanying rapid growth in the battery value chain will also create significant revenue pools in materials and cell manufacturing.

Given this expected growth, why aren’t investors keener on battery producers? In fact, the Stoxx Global Lithium and Battery Producers Index has returned a negative -29% over the past 12 months, underperforming the S&P Global Clean Energy Index by -20 ppts. Several issues have caused problems. Chinese battery production capacity has expanded rapidly, leading to a glut in domestic and global supply. Average global battery cell prices fell by over -16% in 2023, according to BloombergNEF. There are also expectations of structural change in the market as part of global efforts to diversify supply chains.

For investors, the challenge is how to navigate such short-term volatility while positioning for possible long-term gains. There appears to be continuing investor optimism about the battery sector’s medium-term prospects, with double-digit earnings growth expected by 2025, making the sector's next twelve months (NTM) price-to-earnings (P/E) ratio of around 20x potentially attractive, especially given the high double-digit earnings growth expected by 2025. But don’t expect immediate illumination.

The number of anti-ESG resolutions has risen sharply at company shareholder meetings since 2021. [2] The actual number of these anti-ESG resolutions is still small and the average level of shareholder support for these resolutions has fallen back from 9% in 2022 to 2% in 2024 [3]. But it’s still worth digging a little deeper into what is driving them. In the U.S., most are focused on diversity or political influence-related themes. Only around 15% are climate-related, often arguing that efforts to curb greenhouse gas emissions are (in the view of the proposers) too expensive, probably futile and based on questionable science.

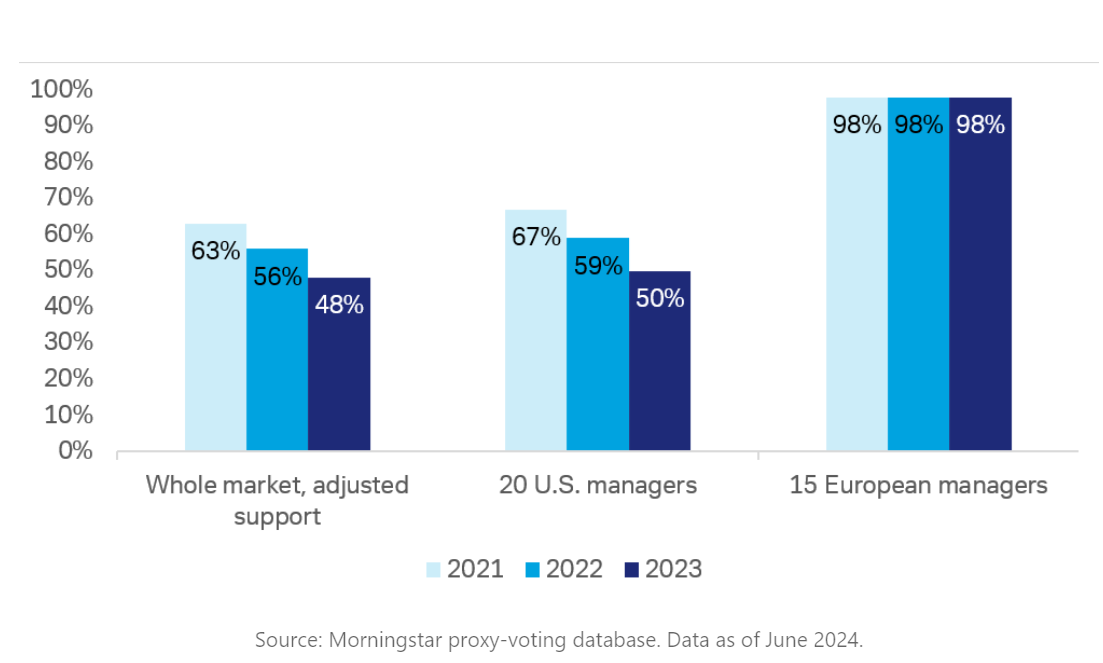

It may be useful to look at the issue from a different perspective: are key fund managers previously keen on pro- ESG measures now cooling on the subject? The answer depends on where you are sitting. Support from key U.S. fund managers for ESGM measures has noticeably softened (see chart below) but remains extremely high in Europe, as the chart below from Morningstar Manager Research shows. [4] European fund managers’ positive sentiment does seem to reflect broader regional enthusiasm for ESG overall, but shouldn’t be taken for granted.

Recent weeks have seen further reports of biofuel plant construction postponement, or of mothballing of existing plants. Some refiners have also cut expected biofuel refining margins, impacting their own stock prices. The reasons behind biofuels’ current malaise are various. One problem is a mismatch between the determinants of revenues and costs: the amount refiners can charge for biofuels is limited by the price of regular diesel, which has fallen, but biofuel production input costs (e.g. waste and residue feedstock) are unconnected do this and still high. Another problem is that previous increases in supply (e.g. of renewable diesel from U.S. plants) are putting downward pressure on prices for low-emissions biofuels, adding to growing concerns about the impact of higher Chinese biofuels production. The overall impact on the biofuels industry is likely to be substantial: one leading European biofuels refiner recently reduced its expected renewables sales volumes for 2024 by 10%.

This downbeat news contrasts with positive recent talk and action on biofuels’ use in aviation and other transportation. (New fuel EU maritime rules come into force next January, for example.) It should also remind us that just because a sector is largely driven by government policy, it doesn’t mean that it is necessarily stable or attractive for investors.

The outlook for the biofuels market is currently largely driven by government commitments to (in future) blend a given proportion of biofuels with traditional hydrocarbons in fuel used in certain sectors (e.g. aviation or maritime fuels). With biofuels relatively expensive, there is no short-term narrow economic rationale for this. Instead, the reason that governments are now mandating biofuels/hydrocarbons blending is that it offers a relatively easy way for them to cut emissions in some hard-to-decarbonize sectors using existing internal combustion technology. (Unlike cars, for example, electric boats or airplanes are not yet commercially feasible.)

Over the medium term, these government commitments imply substantial boost in demand for biofuels. But, in the interim, biofuels suppliers and users find themselves in a market subject to ongoing structural change, for example through repurposing of additional plants to biofuels, and open to new entrants (e.g. China). Add to this some scepticism about whether governments will maintain or scale-back blending commitments (as Sweden has done), and you have a recipe for market volatility. I don’t think that government policy, for all its good intentions, can ever eliminate this.

This article is also published on the author's blog. illuminem Voices is a democratic space presenting the thoughts and opinions of leading Sustainability & Energy writers, their opinions do not necessarily represent those of illuminem.

Jonathan Lishawa

AI · Energy Transition

Olaoluwa John Adeleke

Power Grid · Power & Utilities

Alex Hong

Energy Transition · Energy

Financial Times

Power Grid · Power & Utilities

The Guardian

Oil & Gas · Upstream

Eurasia Review

Hydrogen · Energy