“Why?” is the most important question that never gets asked in ESG discussions. Or, at least, doesn’t get asked enough.

Why?

Because asking the question “Why?” more often and earlier would allow us to (1) avoid spending millions of hours and billions of dollars on ineffective, often pointless activities, and (2) focus the mind on those activities that actually matter.

Emissions disclosure seems to me a great example of this general rule.

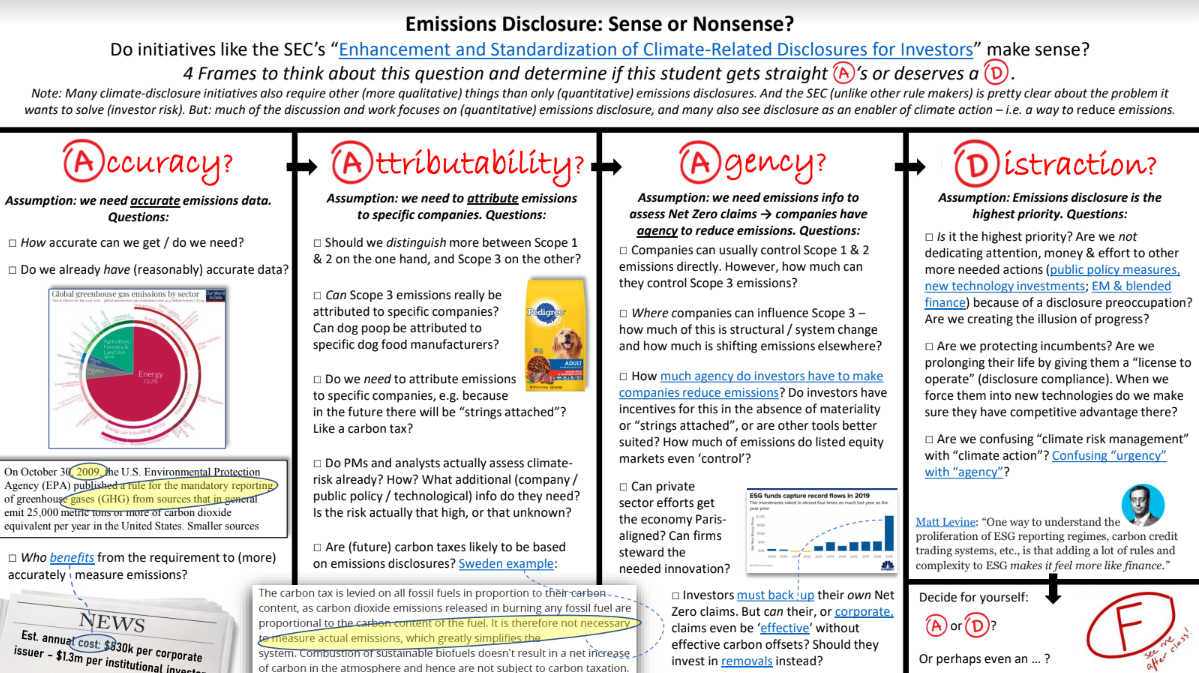

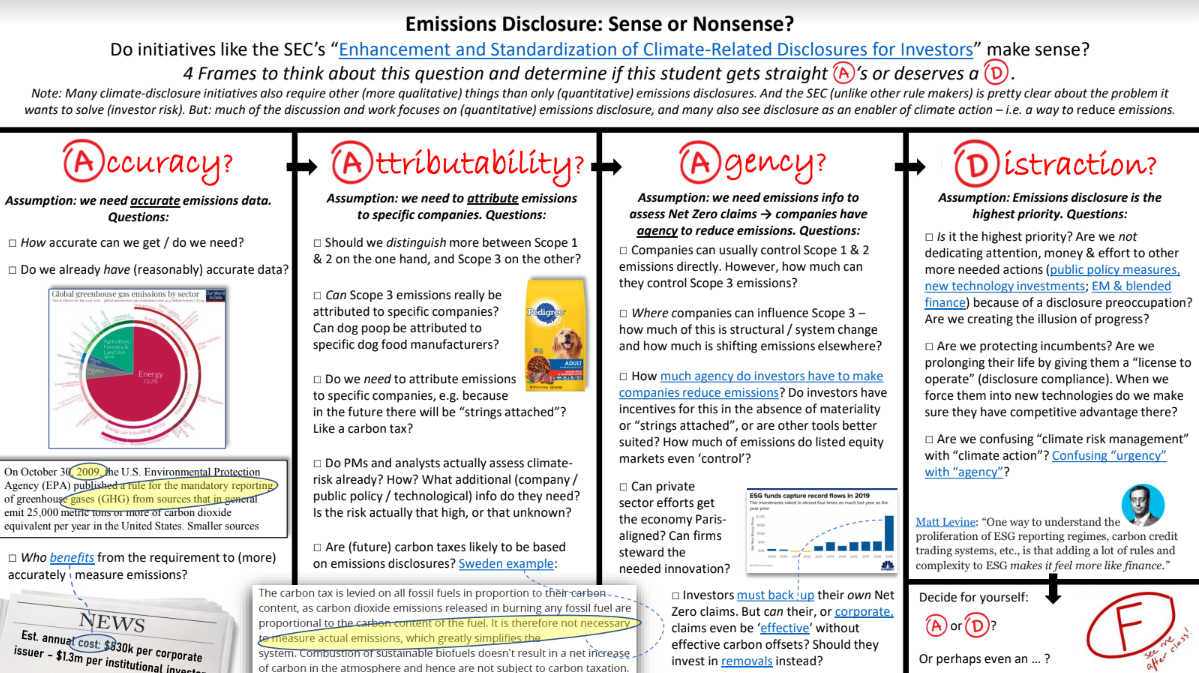

Especially since the SEC’s recent proposed regulation Enhancement and Standardization of Climate-Related Disclosures for Investors was launched, the general sense in the ESG community seems to be that this would put companies and investors on the right track in terms of dealing with climate change. In other words: people feel the proposal makes sense.

But asking the right “why?” questions allows us to see that this is at best relative – whether emissions disclosure makes sense depends on what you want to achieve with it – and at worst is a costly distraction from the real work that needs to be done to address climate change.

(To be fair, the SEC proposal is not exclusively about emissions disclosure and also discusses other, more qualitative measures. Nonetheless, most of the discussion after the proposal was launched has been about – the more quantitative – emissions disclosure elements).

So, what are the right “Why” questions? There are four:

To see the full graphic with links to further reading click here.

Accuracy

Proponents of emissions disclosure put much emphasis on the need for more accurate data. On the face of it, this seems smart. Only if you have good data on a given problem you can fix it. But, still, it makes sense to ask the question “why is (more) accuracy important?”:

- How accurate, or complete, can we get, or do we need? I’m not a climate scientist or engineer but it seems to me that the concept ‘emissions’ is by nature fuzzy and intangible and defies precise quantification. But also, how accurate is really needed? Of course it depends what you use the data for, but probably with most things that you need emissions data for, 100% accuracy is not necessary. We’ll also revisit this question under 3. below.

- How accurate is the data we already have? Again, I’m no expert but I did half an hour of Googling on the topic and found a few websites, including this one, that seemed to offer pretty detailed emissions information, broken down by sector. Also I learned that at least in the US, rules have been in place since 2009 requiring larger companies to report emissions. I have no idea to what extent companies comply with these rules but has anyone checked before writing the new rule?

- Who would benefit most from the requirement? In wondering “why” we are confronted with particular laws & regulations it’s always instructive to ask this question too. So, who would benefit most from the requirement to get even more accurate emissions information? Well, I found a study indicating what the costs of climate disclosure are for corporate issuers and for institutional investors. My back-of-the-envelope calculation of the entire market (in the US alone) is $10 billion. Annually. Now, could it be that the data providers, auditors and consulting firms who would like a piece of this market had anything to do with the creation of this rule, and the emphasis on accuracy?

Attributability

The second “why” question has to do with attribution of emissions to particular corporations or investors. This is obviously at the core of proposals such as the SEC’s: it’s not good enough to know at a planetary level how much we’re pumping into the air – which is causing catastrophic climate change – we want to know who is doing it. Again, on the face of it, this kind of makes sense. If you want to solve a problem, first you need to know who caused it. However: questions, questions… Why do we need to attribute emissions to specific companies or investors?

- Scope 1 & 2, or Scope 3? If we’re talking about attribution, should we start by distinguishing between Scope 1 & 2 emissions on the one hand, and Scope 3 on the other? The difference is more relevant than you might imagine: scope 1 & 2 emissions are more or less under direct control of corporations – i.e. are easy to attribute – but scope 3 emissions, generally, are not. And in most industries, scope 3 emissions are (by far) the most significant component. You could argue, as people frequently do, that “one person’s scope 3 emission is another’s scope 1 emission”, and that’s certainly true – but how does that help us? What if that second person is YOU, driving your car to work every day. How useful, or ‘correct’, is it to say that your emissions are also Scope 3 emissions of some oil company? I would argue this is not useful at all.

- Dog Food Manufacturer’s Scope 3 Emissions? To illustrate the futility of this approach, I sometimes use the “dog poop analogy”. One could argue that dog poop is “Scope 3 emissions of dog food manufacturers”. And we would probably all agree that dog poop is annoying and irritating and something we should do more to address (if obviously not on the scale or urgency of climate change). But who in their right mind – in an effort to do something about dog poop – would start by trying to first attribute specific dog poop to dog food manufacturers? Can you imagine a regulation like “Dog Food Manufacturers’ Scope 3 Emissions Disclosure Requirement”? How would this help us?

- Why Attribution? But it’s also worth asking the question if attribution to specific companies is really needed. Do portfolio managers and analysts really need this information to assess climate-related investment risk for a particular company? It seems to me that they are more interested in the likelihood of public policy measures and how they will impact specific industries and supply chains. And to the extent company-specific information is needed, quite a lot of it is already available or can be assessed through proxies (see also question 1.).

- Step one towards Carbon Tax? It has also been argued that attribution of emissions is important because it is a necessary prerequisite for introducing carbon taxes. But … if you look at Sweden’s carbon tax for example, the Swedes state explicitly that implementing the tax did not require emissions measurement. You could also, for example, simply levy the tax at … the point of sale? For example, when you buy gas to fill up your tank? Or when you pay your gas or electricity bill?

Agency

All of the above prompts questions of “agency”: the unspoken assumption appears to be that we need more accurate emissions information, attributed to specific companies because then … they will do something about it? This, however, assumes those companies have agency, in other words that they can control or influence those emissions. Therefore, it is worth asking the following:

- Do companies have agency in systemic issues? Companies can do – and should do – quite a bit to reduce Scope 1 and 2. But Scope 3 is the big problem, because GHG emissions is what we would call a systemic issue; it is a problem associated with the fact that since the industrial revolution most sectors (electricity, housing, transportation, industry) rely on complex international (fossil fuel-based) energy systems, that not even the biggest players in those sectors can do much to change. And in how our society works, most of the agency to change those systems resides with governments, not the private sector. Governments can create laws, taxes and subsidies, or invest in R&D, in order to nudge sectors from one technology to another.

- If there’s agency, are companies or investors well-placed to act? This leads to another question: even if firms have agency, are they also incentivized and organized to steward change and innovation? Investors “control” only about 1/3 of emissions (also because many large emittors are government-owned). And incumbent firms likely don’t have the incentives. For example, can we expect large oil companies to put their hearts and souls (and capex) into renewables if oil, today, is vastly more profitable? But also, can we expect oil companies – the ‘winners’ in today’s technology – to be the winners in tomorrow’s technologies, recognizing that those are vastly different technologies requiring vastly different competitive advantages?

- Wow - did you see how far questions of “agency” have taken us away from the need to have emissions disclosure?

Distraction

Therefore, my last “why” question leads us to the possibility that this emphasis on emissions disclosure is actually a big distraction.

- Why is emissions disclosure such a priority? If you start thinking about the question “how will we tackle climate change, and who has agency?”, you start to realize we kind of know how we will tackle climate change (carbon pricing, sector regulation, government-subsidized investment in R&D and new technologies) and that we sort of know who should be taking the lead: governments (you know, they who actually signed the Paris Agreement). And that for all that stuff we don’t really … need more accurate disclosure of emissions, attributable to companies and investors who don’t have agency?

So, think about emissions disclosure again and ask yourself the question “Why do we need it? Why would others demand it? Why should we put so much emphasis on it?”

Think about Accuracy, Attributability and Agency and then ask yourself the question: what are we trying to achieve? Point fingers at companies? Apportion blame for causing the problem? Risk management? Fixing climate change? Are we on the right track?

Or is this just a Distraction?

Energy Voices is a democratic space presenting the thoughts and opinions of leading Energy & Sustainability writers, their opinions do not necessarily represent those of illuminem.