Autonomy and pluriversal energy futures in Ladakh, India

· 11 min read

In Ladakh, an ecologically complex trans-Himalayan region of India, two visions of energy transition are in conflict. The first embodies a place-based, time tested, indigenous-led, and socio-ecological understanding of transition. This conception of transition emphasises on low-impact passive energy development and lifestyles as a model for both regional and global climate action. The second is a top-down and technocratic approach, championed by the Government of India. This vision aims to open up Ladakh to large-scale solar farms, geothermal and green hydrogen explorations, and critical mineral mining. The objective is to transmit so-called “renewable” energy to high-consumption centres in India.

To determine which of these contrasting and competing visions prevail lies the pivotal question of autonomy for Ladakh. This is being demanded through inclusion under the Indian Constitution’s Sixth Schedule, and conversion into full statehood. The Sixth Schedule of the Indian Constitution provides for autonomy and self governance to tribal areas in four states of Northeast India. It facilitates the creation of autonomous councils vested with legislative, judicial, executive, and financial powers. Decisions regarding land use are vested to these councils. The Sixth Schedule was established to preserve the distinct culture of tribal areas in India. Its implementation in Ladakh is also argued from the point of view of climate change and the urgent need to preserve sensitive landscapes and cultures and to strengthen grassroots governance. The Sixth Schedule would grant the local Indigenous population, through their political representatives, formal control over their lands and resources. Additionally, there are demands to convert Ladakh from its current status of a Union Territory, under the control of the central government, to a full state. This is meant to provide Ladakh with democratic self-governance through an elected legislature.

Based on a series of protests in 2023 and 2024, autonomy is a crucial precondition for safeguarding and further developing pluriversal futures. The concept of a pluriverse challenges the idea of a single modernist and universal reality, driven by ideas of development. Instead, it proposes a world where many worldviews and practices exist, grounded in diverse ontologies, epistemologies and ways of being.

Such notions perceive places like Ladakh singularly as peripheral and potential sacrifice zones for the modernist energy transition. What Ladakh is facing is representative of many “peripheral” territories, especially those inhabited by Indigenous Peoples and other traditional communities, and/or by nonhumans. The term green colonialism is increasingly being used to describe projects that focus solely on the decarbonisation credentials of energy to acquire and transform land, while ignoring to address the socioecological impacts of these projects. Furthermore, green colonialism ignores socioecological ideas and practices of transformation. In the case of Ladakh, the term internal colonialism is appropriate, where the government exercises control over the lives and lands of minority groups, without granting them full democratic rights. Under these circumstances, Indigenous and rural populations are especially vulnerable to green infrastructure colonialism and risk losing access to their traditional lands. Ironically, it is these very Indigenous Peoples that are actively engaged in combating climate change. Indigenous Peoples are holders of pluriversal knowledge of how to harness energy without negatively impacting relationships to the land and its nonhuman habitants. From a pluriversal perspective, the so-called peripheries, resisting green colonialism, then become central sites of differently seeing, organising and thinking about nature and climate.

The protests in Ladakh are demanding autonomy and rejecting autocratic top-down developmental projects. Additionally, the protests have become a moment to foreground the existing and functional pluriversal technologies like passive solar construction and practices like low-impact living. These practices exist and flourish within local socio-ecological boundaries in Ladakh. The act of resisting, in this case, is not merely the act of stopping extraction and the imposition of modernist development by the Indian Government. Rather, it points towards alternative relations and practices that people have with the land and the sun that shines generously on it.

The Ladakh region is located, at an average altitude of 3000 metres above sea level, in the trans-Himalayan part of India, between Tibet and Kashmir. It covers a total area of 59,146 sq.km. and is classified as a cold desert landscape, with winter temperatures falling to−20°C. Annually, Ladakh has an average of 300 days of clear sunshine, making it an ideal location for harvesting solar energy. Ladakh’s socio-ecologically rich landscape has flourished in challenging geographical conditions. It is estimated that 97% of the 274,289 Ladakhi population is Indigenous, with a wide range of lifestyles and customs. This socio-ecological diversity is central to the demand for protection under the Sixth Schedule of the Indian Constitution as well as full democratic rights to make developmental decisions.

Politically, Ladakh was an independent kingdom for over a thousand years, before being subjugated by rulers from Kashmir. It was made part of the state of Jammu and Kashmir when India became an independent country in 1947, and calls for autonomy have persisted ever since.

These include struggle to obtain the status of Scheduled Tribes under India’s Constitution, and to get a Union Territory status. As an interim measure, Ladakh was able to obtain relative autonomy through the Ladakh Autonomous Hill Development Council Act 1995.Following the 2019 abrogation of Article 370, Jammu and Kashmir became a Union Territory, and Ladakh followed suit, coming under direct central government control.

The conversion to a Union Territory status was initially celebrated by people in the district of Leh. However, it was soon clear that without having its own legislative assembly, this was only transferring power to New Delhi. Quickly, Ladakhis realised that constitutional safeguards would be needed to protect their socio-ecological diversity from external commercial and political interests. Furthermore, full democratic rights, exercised through elected representatives in the state assembly, are equally necessary to make decisions on land and resources.

In its 2019 election manifesto, the Bhartiya Janata Party promised Ladakh Sixth Schedule status, but the unfulfilled promise and lack of a legislative assembly sparked protests in 2023 and 2024. Climate activist Sonam Wangchuk played a key role, emphasizing the need for constitutional protections, particularly as Ladakh faces the impacts of climate change, such as glacial melts, and seeks to preserve Indigenous ways of life.

Ladakhis have a long tradition of living lives synchronised to harvest the power of the sun in non-extractive and non-exploitative ways.The concept expands the universal imaginary of renewable energy infrastructure dominated by large-scale solar farms and wind turbines set against inert landscapes. Additionally, the concept of energy sovereignty demands that for as fundamental a human need as energy, people and communities should have control over how it is generated, distributed and used.

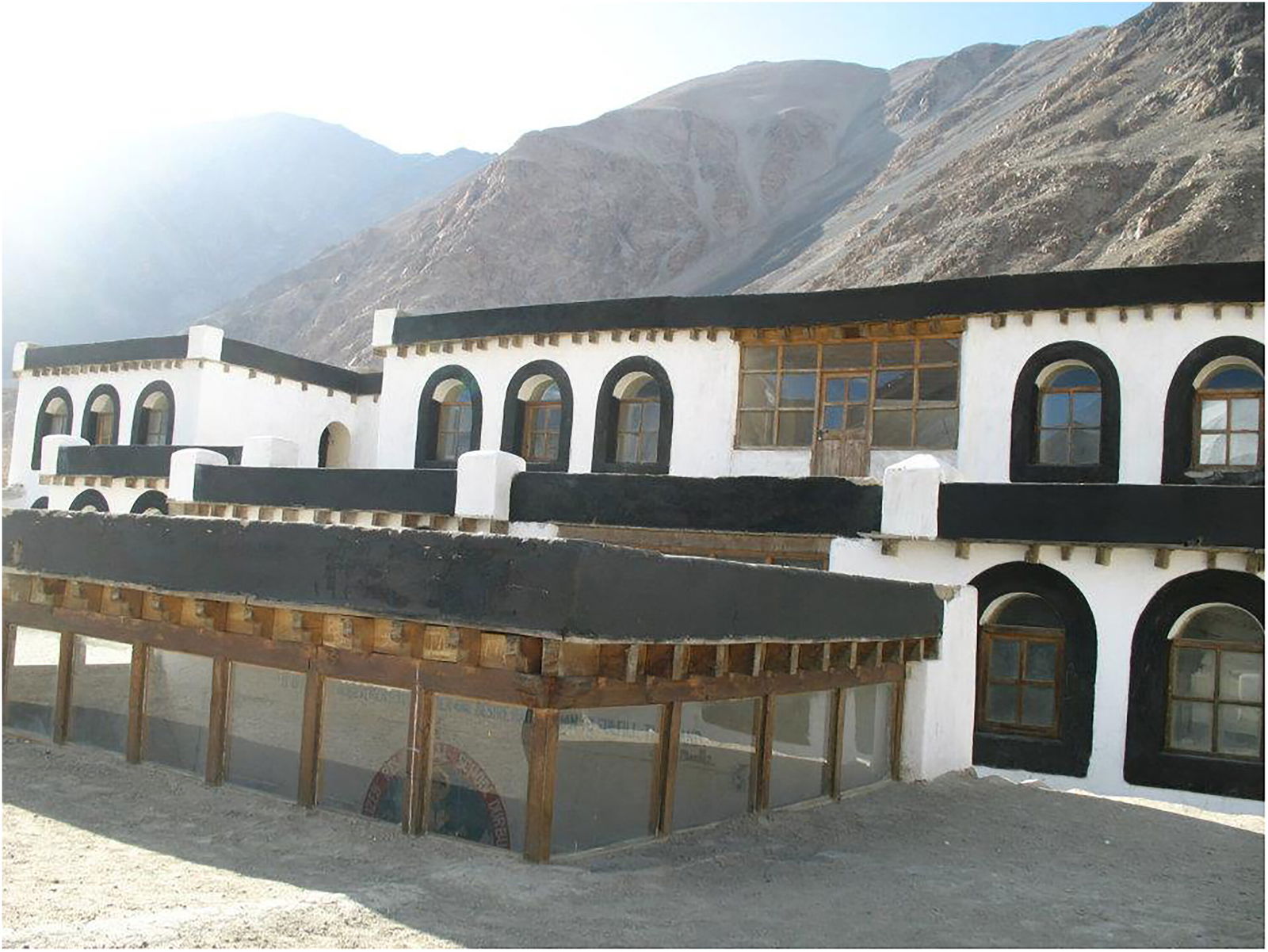

The passive solar-earth buildings of Ladakh are an excellent case in point. Ladakh has a long tradition of building with earth, the locally available carbon-neutral building material. Passive solar-earth houses in Ladakh significantly reduce the need for carbon-based fuels for heating. In winter, when temperatures drop to −20°C, these homes maintain an indoor temperature of +15°C without mechanical heating. These buildings combine local climate knowledge with efficient use of the sun and earth. Features like parabolic reflectors for cooking, dry toilets to save water, and greenhouses for winter food cultivation further minimize the energy footprint.

Other than passive solar-earth buildings, Ladakh has well-functioning decentralised active solar systems as well. The SECMOL (Students’ Educational and Cultural Movement of Ladakh) school campus located in Phey, Ladakh is a synthesis of both. The residential school for 40 students and supporting staff members is completely off-grid. The energy used in the school for pumping water and electricity is produced on campus through solar panels. There is however a conscious restraint on the use of active solar energy, which is substituted by passive earth buildings as well as conscious lifestyles that are synchronised with the sunlit hours. The energy system at the SECMOL campus is democratically managed by the students of the school, further deepening energy sovereignty and independence.

Another example stems from the Pishu village in the Zanskar Valley, an area already stressed by water scarcity and further exacerbated by climate change. Here, the local community and the Navikarana Trust have collaborated to use solar energy to pump water from a nearby water reservoir. This has helped the community to access water for their everyday needs at a time when glacial water is increasingly becoming unpredictable. These examples exhibit important lessons for designing future energy systems that are co-created with local knowledge, address societal needs and respond to the ecological limits of the local geography.

In 2020, the Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi announced a vision for developing Ladakh as a carbon neutral region. However, there was no acknowledgement that Ladakh is already carbon negative, given its large landmass, sparse population and low-impact lifestyles. Furthermore, there was no engagement with the existing wealth of Ladakh’s pluriversal knowledge and practices of low-carbon living. Instead, most of the ideas were towards implementing new (supposedly) carbon neutral technologies like electric buses to ameliorate the anticipated increase in emission arising from opening Ladakh to future development.

The national level budget of 2023 earmarked a sum of Rs 8300 crore (approximately 994.17 million USD) towards a 13-GW solar and wind energy project in Ladakh. This project would “evacuate” energy out of Ladakh through a 900-km-long intra-state transmission system. While this project has been lauded nationally for showing India’s commitment towards an energy transition, environment and livelihood rights activists in and outside Ladakh have raised concerns about the siting of the solar farm in the Changthang area of Ladakh. This would enclose pasture lands, disturb wildlife habitats, and stress local water resources. Furthermore, the absence of consultation with the impacted population as well as the elected representatives has been the cause of protest and mobilisation against the project. The planning and implementation of large-scale solar parks are a stark contrast to the tradition of how solar power has been understood, developed and shared in Ladakh. The absence of constitutional autonomy, environmental safeguards and statehood, make it difficult to oppose the influx of such projects in Ladakh.

Problems arise when the government plans and policies disregard the knowledge and ownership of Ladakhis, and announce and execute projects without prior consultation, do not share the benefits and take no accountability for the socio-ecological impacts. It is against these colonial tendencies of land and resource capture, and lack of democratic processes, that the people of Ladakh are protesting and demanding full democratic rights and autonomy.

The protests demanding autonomy in Ladakh nudge us to see that resistance movements do not always create new alternatives. Many times, they are defending well-working, pre-existing, and evolving systems. However, these socio-ecological practices or ways of life often clash against mainstream ideas of technological development, progress and energy transition. The act of resistance is then towards defending autonomy that allowed for such alternatives to flourish in the first place.

The Indian government and multiple energy companies may just be “discovering" Ladakh as a resource to power their energy future. However, the people of Ladakh have a long-standing and non-extractive relationship with solar energy. Their methods, technologies and practices may not look similar to modernist universalist notions of energy transition. Rather, they are a stark reminder of what place-based pluriversal alternatives can look like. In their insistence for autonomy, Ladakhis demand a democracy that is different from today’s dominant liberal or electoral form. Instead of concentrating power in national and state capitals where elected parties rule, Ladakh prefers decentralisation, mindful of ecological and cultural conditions, in what could be called eco-swaraj or radical ecological democracy. As Ladakh mobilises to protect its unique ecology and culture, the rest of India and the world need to understand and stand in solidarity with it.

Autonomy and constitutional safeguards are a necessary, but not sufficient condition, to generate pathways that achieve well-being without sacrificing Ladakh’s unique environment and people. Ladakhi leaders like Chhering Dorjey Lakruk, and youth like Akhtar Ali, are placing socio-ecological struggles at the centre of the movement for autonomy. National networks like Vikalp Sangam have also argued that, in addition to the Sixth Schedule, Ladakh should be brought under the Fifth Schedule of the Constitution of India, which empowers village assemblies in areas inhabited by Scheduled Tribes. An insistence on decentralised governance, facilitated through the Fifth and Sixth Schedules and building capacities for local decision-making, is a safeguard against capture of power and resources by elites at the state and national level. This is crucial to lay the foundations of a socio-ecologically just future in Ladakh.

This article has been adapted from the original research article titled “Autonomy and pluriversal energy futures in Ladakh, India”, published in the journal of Human Geography and can be accessed here. illuminem Voices is a democratic space presenting the thoughts and opinions of leading Sustainability & Energy writers, their opinions do not necessarily represent those of illuminem.

Olaoluwa John Adeleke

Power Grid · Power & Utilities

Purva Jain

Energy Transition · Energy Management & Efficiency

illuminem briefings

Energy Transition · Energy Management & Efficiency

Forbes

Energy Transition · Energy Management & Efficiency

China Daily

Energy Transition · Energy Management & Efficiency

International Energy Agency

Energy Management & Efficiency · Energy Transition