Anatomy of a fall: Europe’s deindustrialisation

· 14 min read

Europe is facing a triple crisis: a climate crisis, an energy crisis and an industry crisis. The last crisis is still underrated and is the topic of this contribution. The war in Ukraine has triggered an explosion of energy prices in Europe, which has now eased. However, the energy costs for European industry remain significantly higher than before 2022 and 2-3 times higher than in the US or China. Energy-intensive industries (EIIs) like chemicals, steel and aluminium have responded with production curtailments and temporary shutdowns. The resumption of production since the easing of energy prices has so far been partial at best. In some cases, we have already seen permanent shutdowns and relocations away from Europe to regions with lower energy cost levels. This implies that deindustrialisation in Europe is currently already happening. Policymakers in countries like Germany and France are very worried about this new trend and are trying to come up with policy responses. The critical question now is what a comprehensive European policy response will look like. Before discussing this, let’s take a closer look at the seriousness of the problem.

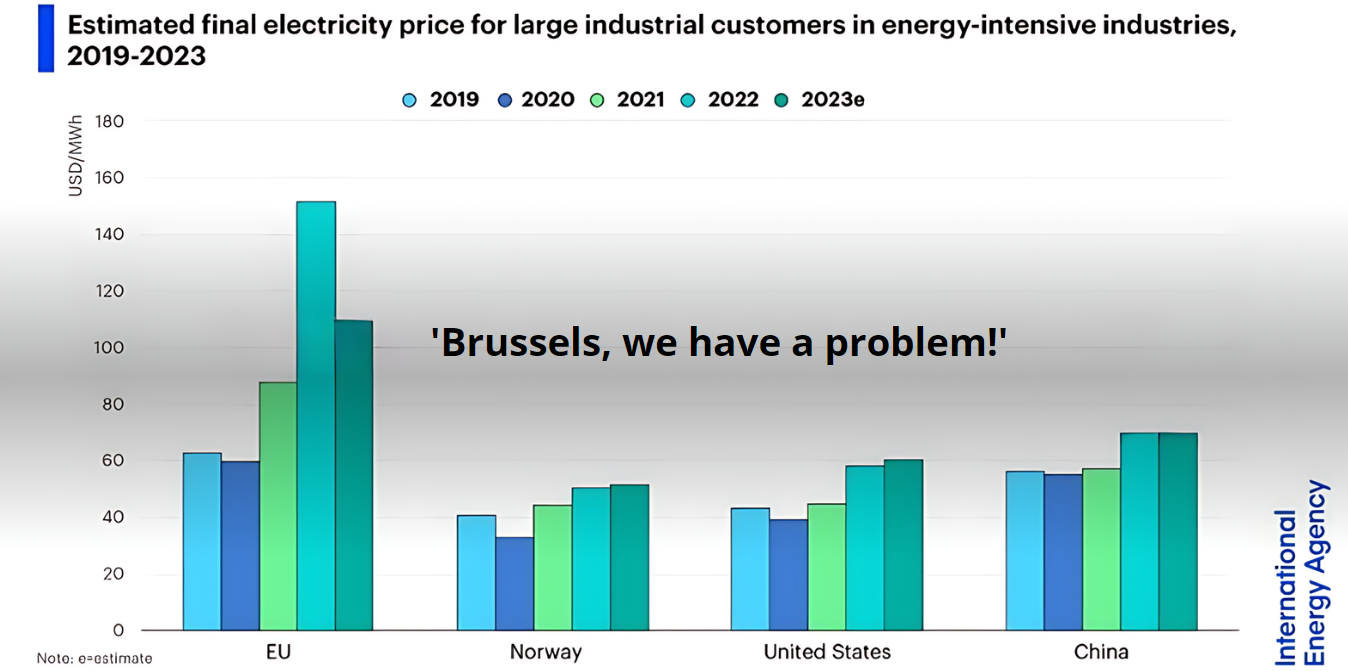

As the saying goes: a picture is worth more than a thousand words. That is certainly true for the graph below.

This graph demonstrates clearly how much the power price differential between EU industry and its competitors has increased.[1] It was already significant before the Ukraine war but has now become unsustainably large, in my view. But perhaps, one may argue, things will get better in the years to come? Well, not really, as the following graph shows unambiguously.

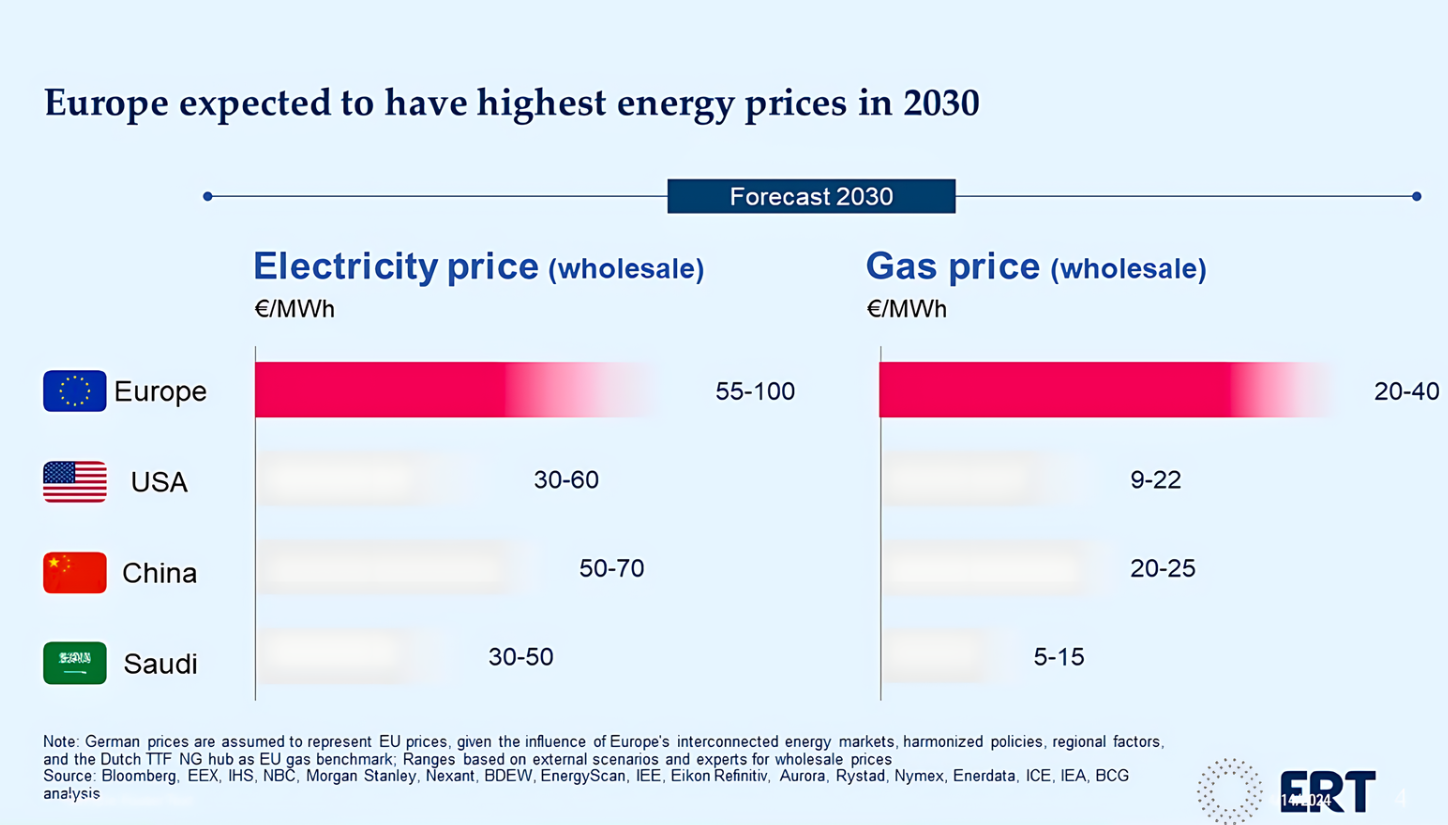

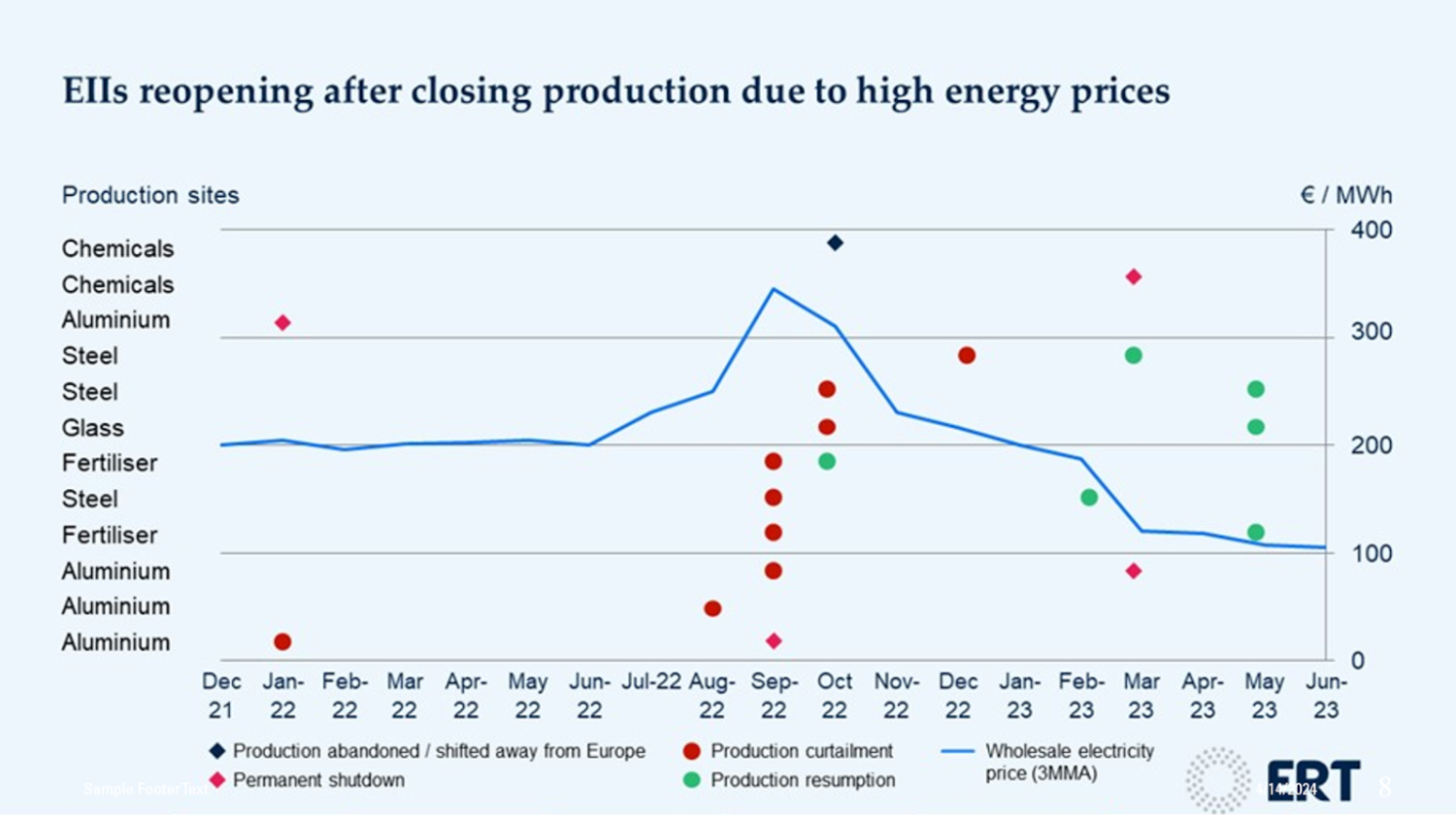

According to the projections in the graph above, there is no relief in sight for EU industry in the period up to 2030.[2] And that is the case for both electricity and gas prices industry is paying. Against this background, it becomes clear that EU industry is in dire straits. We can see this in the relative lack of recovery in industrial gas use[3] and we can hear it in the rapidly increasing loudness of alarm bells rang by European industrial circles, as witnessed by the Antwerp declaration and most recently by the reports of the ERT.[4] More importantly, industry is voting by its feet: we are witnessing an increasing number of production limits and closures across many sectors. The graph below shows this clearly.

As the graph above only covers the period up to June 2023, the actual situation may already be worse than portrayed here.[5] To some extent, it will be unavoidable and even natural that we will see a relocation of energy-intensive parts of industrial value chains to regions with low energy prices. But the current emerging deindustrialisation wave seems of a much larger scale. In addition, the Emission Trading System (ETS) puts structural upward pressure on the European carbon prices, whereas the free allocations for industry are poised to be phased out in the period up to 2040. The Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM) that will enter into force in 2026 does shelter EU industry from un-priced carbon-intensive industrial imports, but so far still has some flaws - most notably, the absence of export rebates and of inclusion of downstream markets.[6]

On top of the energy price disadvantage, European industry is seriously hampered in its decarbonisation trajectory by electricity grid congestion and an emerging supply gap in low-emission hydrogen. Not surprisingly perhaps, the foreign direct investment into the EU has also sharply declined in recent years. In particular for the manufacturing industry, Europe is no longer an attractive investment destination. Meanwhile, the US has positioned itself as a vast clean energy power, with the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA), the Infrastructure Law and the recent $6bn programme supporting the decarbonisation of the manufacturing industry. All of these programmes are currently attracting significant investment also from European-based companies.[7] The sad reality is therefore that deindustrialisation in Europe is not just a threat, it is already happening in practice.

What are the implications of this new trend? In some European countries policy makers are (silently or not) rejoicing because CO2 emissions will decline and ambitious climate policy targets will be much easier to achieve. However, in most European countries policy makers worry that decarbonisation through deindustrialisation may just boil down to shifting emissions to regions outside Europe and worsening strategic autonomy in clean energy manufacturing (solar, wind, batteries, electrolysers, heat pumps etc.) and defence, whilst causing economic decline and thus impoverishment inside Europe. In what is now called the ‘clean-tech race’, Europe is falling behind the US and China. Longer-term, this also undermines the European economic growth potential, since clean energy has recently emerged as one of the critical drivers of economic growth.[8] Understandably, the ‘clean-tech race’ does cause some worries with regard to fiscal costs and protectionist tendencies [9]. Still, the EU can in my view simply not afford to ignore the fundamental changes in the global competion.

In Germany, the European country with one of the highest shares of manufacturing industry in GDP in the EU, the fear of deindustrialisation is widespread and widely reported.[10] The German government started working on policy responses to the industry crisis early. In 2023 it came up with a scheme of energy tax relief and stabilisation of energy prices for energy-intensive industry. More recently, it has introduced the promising Carbon Contracts for Difference (CCfD) mechanism that helps the manufacturing industry to bridge the gap between ‘grey’ and ‘green’ technologies. The German government has also taken other measures to accelerate the availability of decarbonisation options for industry, e.g. low-emission hydrogen and Carbon Capture, Utilisation and Storage (CCUS).

In France, deindustrialisation has already been underway for a longer time. The debate in France revolves around the urgent need to reindustrialise to boost long-term economic performance and strategic autonomy. The government is working on providing similar policy responses as have been formulated in Germany. The French government has an official target to lift the share of manufacturing in GDP from 10 to 15%. The French Minister of Economy and Finance, Bruno Le Maire, has called reindustrialisation “la mere de toutes les batailles”. [11] In the Netherlands, however, the government has not yet announced a general policy response, although it has acknowledged that the energy prices facing industry in the Netherlands are even higher than those in Germany or Belgium.[12] Instead, the Dutch government is in the process of designing tailored policy packages for the most significant industrial companies, e.g. ASML and Tata Steel.

In a world of geopolitical fragmentation and a global clean-tech race the European policy response can’t only depend on individual member states. That is why the topic of shaping a European industrial policy response has recently risen to the top of the EU agenda.[13] European industry urgently needs access to much larger volumes of clean energy against affordable prices. Current policies simply fall short of providing this in a timely way. Public and private investment in clean energy in the EU need to be ramped up significantly. Only for low-emission hydrogen, it is estimated that Europe might need public support in the order of EUR 300-543bn over the next 10 years to bridge the cost gap between grey and low-emission hydrogen.[14]

The Net Zero Industry Act (NZIA), just approved by the European Parliament, is seen as a helpful first step, but certainly insufficient as it lacks adequate funding. IEA Chief Fatih Birol has called for ‘a new industrial master plan’ for Europe.[15] The April 2024 Summit of EU leaders concluded that Europe needs a new Competitiveness Deal. To work out the details of this will most likely become one of the top priorities of the new European Commission to be formed after the June 2024 European elections. To help shape this, the recent report by former Italian Prime Minister Letta provides valuable input.[16] His most remarkable proposals include: the establishment of a Clean Energy Delivery Agency to centralise the funding of programmes and serve as a one-stop shop for industry; demand creation for clean technologies through financial instruments and a Clean Energy Deployment Fund to facilitate investment in net-zero technologies; new financial instruments like Green Bonds to attract private capital for infrastructure projects. In addition, the Letta report rightly stresses the need for much higher investment in one of Europe’s strongest assets, a continent-wide energy grid (electricity, hydrogen, CCS), as well as developing energy infrastructure projects of mutual interest with partners in (North-) Africa and other neighbouring regions.[17]

Last, but not least, there are high expectations about the upcoming report of former European Central Bank President and Italian Prime Minister Draghi providing more useful ideas to improve Europe’s industrial competitiveness. In a fascinating preview, Draghi focused on the urgency of enabling scale by overcoming market fragmentation in public procurement and the capital market (Capital Market Union), providing public goods like energy grid interconnections and securing the supply of essential resources and inputs like critical minerals. Let me finish by quoting Draghi, ‘restoring our competitiveness is not something we can achieve alone, or only by beating each other, it requires us to act as a European Union in a way we have never before’.[18]

illuminem Voices is a democratic space presenting the thoughts and opinions of leading Sustainability & Energy writers, their opinions do not necessarily represent those of illuminem.

[1] Source: IEA (2024), Electricity 2024, Paris.

[2] Source: European Roundtable for Industry (ERT) (2024), Competitiveness of the European Energy-intensive Industries, 9 April, 2024.

[3] Akos Losz & Anne-Sophie Corbeau, Anatomy of the European Industrial Gas Demand Drop, March 10, 2024. The title of this piece also inspired the title of this blog!

[4] www.antwerp-declaration.eu

[5] Source: ERT (2024).

[6] See e.g. Hydrogen Europe (2022), ETS and CBAM – implications for the hydrogen sector, October.

[7] See e.g. ‘US decarbonisation fund bets on European groups’, Financial Times, 26 March 2024; Department of Energy, Biden-Harris Administration Announces $6 Billion to transform America’s Industrial Sector, Strengthen Manufacturing, and Slash Planet-Warming Emissions, 25 March 2024.

[8]Laura Cozzi et al. (2024), Clean energy is boosting economic growth, IEA commentary, 18 April.

[9] See e.g. Era Debla-Norris et al. (2024), Industrial Policy Is Not a Magic Cure for Slow Growth, IMF Blog, April 10 and ‘IMF urges Europe to avoid subsidy race’, Financial Times, 20 April 2024.

[10] See e.g. ‘Verliert Deutschland seine Industrie?’, Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, 10 Februar, 2024.

[11] Speech 29 March 2024, https://www.vie-publique.fr

[12] See Ministerie van Economische Zaken en Klimaat, Onderzoek electriciteits- en netwerkkosten, 3 april 2024.

[13] European Commission (2024), The Clean transition Dialogues – stocktaking; a strong European industry for a sustainable Europe, 10 April 2024.

[14] Under the assumption of 3mt yearly domestic production and 7mt imports, see speech Pierre-Etienne Franc (Hy24), H2 Colloquium organised by Belgian EU presidency, Liege, 16 February 2024. See also my Illuminem blog with Kirsten Westphal (2022), Now is the time to get the hydrogen off the ground in Europe, Mar 18.

[15] Fatih Birol (2022), ‘Europe needs a new industrial master plan’, Financial Times, December 7.

[16] See Enrico Letta (2024), Much More Than A Market, April 2024, https://www.consilium.europa.eu

[17] See also my Illuminem blog with Kirsten Westphal (2022), Towards a true partnership between the EU and hydrogen exporting countries, Oct 11.

[18] Speech Mario Draghi at the High-Level Conference on the European Pillar of Social Rights, Brussels, April 16, 2024, https://geopolitique.eu/en/2024/04/16/radical-change-is-what-is-needed/ .

Olaoluwa John Adeleke

Human Rights · Environmental Rights

Gokul Shekar

Energy Transition · Energy

Philipp Petry

AI · Power Grid

Financial Times

LNG · Oil & Gas

SolarQuarter

Energy Transition · Energy

The Guardian

Renewables · Solar