All important soil

· 5 min read

Much of the ongoing global extinction is taking place underground. Booming metropolises of biological production and exchange crumble in silence, at a rate of 75 billion tonnes per year. Soil, the most biologically diverse material on Earth, is a cornerstone of life driven to irrelevance by our mechanised understanding of nature. Soil feeds us, its small inhabitants providing nutrients necessary to grow food. Without healthy soils, land agriculture – a foundational human invention that’s shaped commerce, guided empires, and sustains contemporary economies – becomes impossible. Soil protects us, as a natural flood manager and the largest storage capacity for carbon on land, capturing our emissions to limit climate change. Without healthy soils, surface biodiversity and all plants, including forests, would stay in the ground. To maintain these ecosystem services, soil needs to be as diverse as possible.

In Western art, soil has always been represented as a surface, a mere channel that carries the weight of life and hides the dead, devoid of an existence of its own. This lifeless understanding of soil perpetuates today; we suffocate land with chemical fertilisers, disrupting the eco-systemic relationships required for soil to thrive. Our mono-cultural approach to growing food, streamlined for industrial optimisation, has left land in dire condition. Our status quo is thus the very antithesis of biological diversity and resilience.

Protecting soil biodiversity is not only a farmer’s problem, who must abandon eroded land and search for new livelihoods, but an essential pathway for food security, political stability, and climate change mitigation. Yet attention given to soil is slim relative to its weight in the climate and nature puzzle. A combination of decarbonisation-centric governance structures and assumptions that soil sequestration capacity will remain unchanged, has relegated agriculture in climate summits. In particular, small-scale farmers in low-income states asymmetrically hit by drought, are at the heart of innovative solutions but continue to feel overpowered by top-down agribusiness practices.

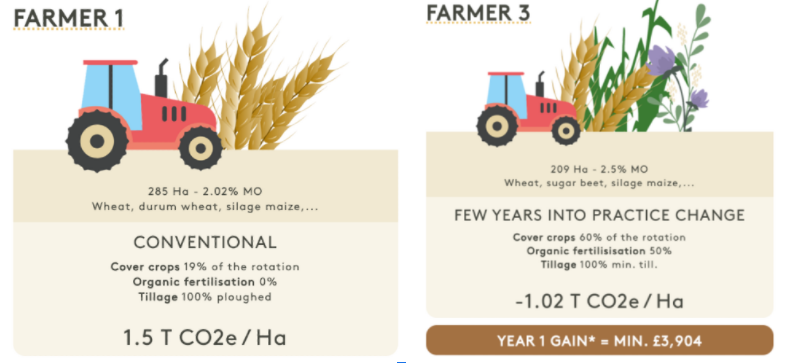

Connecting the dots between agriculture and biodiversity starts at the local level, on the farm. Incentives must exist for farmers who work on low profit margins, and who find it hard to shift production processes. Subsidies can accompany the uptake of ecosystem-based management and even regenerative practices, which boost profitability in the long run. But it’s performance-based compensation that can really convince a move away from mechanised tillage and fertilisers. For example, Soil Capital prices the carbon sequestration capacity of a farmer’s land in the form of a direct payment. 157 European farmers have so far subscribed, with an average of €25 per tonne of carbon. This type of Payment for Ecosystem Services (PES) quantifies the importance of land for agriculture and makes it easier for a farmer to transition away from a rationale of short-term productivity. In China, users of residential and industrial water pay farmers who limit soil erosion. Linkages between upstream land use and infrastructure can be better understood by bringing the work of farmers into the spotlight.

On a more generalised level, reliable accountancy is a requirement for investors and farmers looking to enter this space. However, harmonised methodologies don’t yet exist for measuring soil carbon stock changes. As with much related to nature, soil is a complex system, requiring different practices based on which climate zone, country, region, or even square metre in a field you farm. Data collection can be tricky and accessibility to smallholder farms undermined. Developing industry-wide frameworks, where scientific expertise, farmers’ experience, and reliable datasets are made readily available, can help diffuse norms faster.

On a society-wide level, better representation of soil in our minds, consumption patterns, and politics comes first and foremost through a better understanding of food systems. ‘People don’t know where their food comes from, it’s all theoretical’. Richard Heinberg aptly labels how our hyper-globalised economies have engrained a disconnect between farm and fork; we eat food without questioning the capital – both natural and human – within it. Through our blinded eating habits, we sustain destructive industrial and commercial processes. Processes that annihilate biodiversity, the condition for life. Processes that damage our immune systems and make us more susceptible to developing disease. Processes that waste resources on a gargantuan scale, with harvest the equivalent land size of India and Brazil combined thrown away every year. Exacerbated by pressures from climate change, our food systems are destined to fail, with immense repercussions on human lives. Madagascar’s ongoing famine is testimony to our immense dependence on stable agriculture, directly challenged by our climatic predicament.

David LeZaks highlights health as an emergent axis to address soil erosion and land degradation, for it concerns us all. Better soil treatment can improve food’s nutritional quality, transfer microbial benefits to humans, and eliminate the damaging presence of agrichemicals. Changing what’s in our plates, holding our governments accountable for land protection, supporting local farmers: these decisions are about healthy bodies as much as they are about healthy land. From the individual to the state level, links between nature and survival must increasingly be unlocked.

During a speech connecting nature and geopolitics, UNEP director Inger Andersen succinctly argued that one of the main causes of disaster is our ‘siloed mentality’. Each discipline, institution, or expert drives their solution in a compartmentalised fashion when what’s needed is transversality. Opposite nodes must meet for impactful ideas to emerge. Approaching soil as a financial opportunity, a geopolitical metronome, a doctor, and a bastion of innovation – all at the same time – will expand debates around a material that remains underappreciated. If more biodiverse farming practices become commonplace, our crops will be more productive, more resilient to coming shocks, better for our bodies, they’ll empower local communities and reduce the probability of interstate resource conflicts.

Future Thought Leaders is a democratic space presenting the thoughts and opinions of rising Energy & Sustainability writers, their opinions do not necessarily represent those of illuminem.

Gokul Shekar

Effects · Climate Change

illuminem briefings

Mitigation · Climate Change

illuminem briefings

Climate Change · Environmental Sustainability

Financial Times

Carbon Market · Public Governance

The Guardian

Agriculture · Climate Change

Euronews

Climate Change · Effects