A Nation at War with Itself: Infrastructure

· 11 min read

URGENCY is the message of today and every day until the US finally has the policies in place and acted upon that will lead it to a sustainable environment and economy.

The US is fifteen months away from the 2022 midterm elections. If history repeats itself, as it often does, the Democrats will lose their tenuous hold of majority status in both the Senate and House of Representatives.

Let’s do the math. The Democrats will go into the 2022 midterm elections with a four-seat majority in the House and a sometimes one-vote majority in the Senate.

Since World War II, a president’s party has lost an average of 26 seats in the House and four in the Senate in midterm elections. Should Republicans take control of either or both chambers of Congress, it would prove a catastrophic loss of opportunity for putting the nation irrevocably on the path to a decarbonised economy.

Climate matters would be made even worse if the Democrats were to lose the White House in 2024, whatever their numbers in Congress. Should Former-president Trump or his chosen successor prevail in 2024, it would effectively block the passage of any meaningful proactive federal climate policy well into the decade of the 2030s.

This is the first in an occasional series on US climate policy at a time when uncivil wars are raging within the two major political parties and, indeed, the nation itself. Today’s article focuses on the politics surrounding the infrastructure bill—one of the two legislative vehicles with any chance of turning Mr. Biden’s promised climate plan into a reality. The second critical piece of the policy puzzle, budget reconciliation, will be addressed in the next article in the series.

The fate of these two pieces of legislation—perhaps even more than the outcome of the 2022 elections—will dictate the path the Biden administration takes over the next three years. Although both are important, they are neither of equal weight nor consequence should they fail to be enacted.

The infrastructure bill is all about jobs and updating and repairing roads, bridges, and other essential services, including getting quality internet services to all Americans. Although there are climate-related elements, e.g., electrification of school buses, currently in the bill, the main thrust of the Biden climate plan will be through the reconciliation package.

From an environmental perspective, the passage of a national Clean Electric Standard (CES) is the most critical component of any climate plan. The CES is the foundation upon which the two sectors most responsible for Earth’s warming—electricity and transportation—can be successfully addressed and integrated.

A national CES means plugging electric vehicles into clean energy sources. A CES would permit states to open their power sectors to all non-carbon producing technologies, including new nuclear, waste-to-energy, and solar, wind, and storage. Based on already successful state Renewable Portfolio Standards, a CES would also accommodate emission reduction technologies like carbon capture and sequestration made part of an existing natural gas plant.

The clean energy elements of a reconciliation bill are also job and investment opportunities for both government and the private sector. Beyond the differences in the particular provisions, a CES represents a new way of powering the nation that’s not included in the infrastructure legislation. Given its scope and impact, a CES is politically more problematic than the infrastructure bill.

The entirety of President Biden’s climate agenda is riding on the passage of these two bills. The hard reality is the Democrats have mere months to put either or both in place. With almost near-certainty, climate-related legislation that fails to be signed into law by the end of December is unlikely to make it at all.

President Biden’s initial infrastructure proposal went far beyond traditional projects like building and fixing new roads and bridges. The American Jobs Plan included climate and society-related initiatives like achieving a net-zero carbon power sector by 2035 and public investments for in-home healthcare services for the elderly. It proved too great a stretch in the definition of infrastructure for even moderate Republicans like Senators Collins (R-ME) and Romney (R-UT) to support.

The infrastructure bill now being talked about as bipartisan would use its $1.2 trillion on more traditional infrastructure projects including:

Details of the bill are still being worked on by a bipartisan group led by Senators Sinema (D-AZ) and Portman (R-OH).

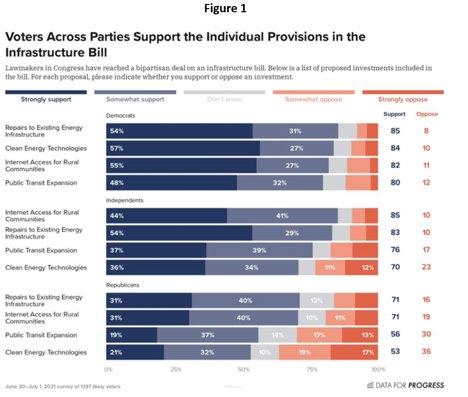

According to a recent poll by Data for Progress, there is unusual bipartisan support for traditional infrastructure measures, e.g., roads and bridges. Support is strongest among Democrats and Independents. Repairs to existing energy infrastructure and internet access for rural communities see over 70 percent support, with relatively little opposition. Republican voters support these two categories with similarly high numbers--71 percent for both. (Figure 1).

Once again, it’s no surprise that clean energy technologies receive more support from Democrats and Independents—84 and 70 percent, respectively. However, the 53 percent support by Republicans is encouraging.

Given that the transportation sector is the largest source of greenhouse gas emissions, support for the expansion of public transit by all three cohorts is similarly encouraging. I wonder if once the pandemic is behind us whether that number would be higher. I’m not sure anyone will feel entirely comfortable jammed into buses and subways before then.

The critical question now is:

Whose pocket or pockets will be picked to pay for whatever provisions of the bipartisan infrastructure bill that are finally agreed on?

Congressional Democrats and Republicans, along with the White House, have set specific criteria that together may be impossible to meet. It means that one side and/or the other will have to give some ground.

Adding pressure to the pay-for debate, conservative Republicans are not fond of one of the President’s proposed funding sources. Biden had proposed having the Internal Revenue Service become more vigorous in chasing down companies and millionaires who failed to pay their fair share of taxes. Yes, Mr. Trump, I think he meant you.

It now appears that this provision will not be in the final compromise bill. It means finding the estimated $100 million that the IRS would have been expected to raise through the stepped-up audits.

President Biden has promised no new taxes for Americans making $400,000 or less. However, he has proposed raising the corporate tax rate to 28 percent from the current 21 percent and forcing multinational corporations to pay a tax to the US on profits booked overseas.

Most of what President Biden is proposing is anathema to Republicans. GOP negotiators have sworn not to accept any deal that rescinds the corporate and individual tax cuts passed during the Trump administration. It should be noted that before the cut, the corporate rate was 35 percent, so Biden is proposing only a partial reversal.

Much of what the Republicans are offering up in terms of funding is contrary to what Biden has promised not to do. For example, the Republicans are proposing to raise the gas tax. The tax was last increased in 1993 when it was set at 18.4 cents per gallon for gasoline and 24.4 cents for diesel. The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) estimates that revenues realized in 2019 from the taxes amounted to around $36.5 billion.

Gas taxes are regressive because lower-income consumers pay a larger proportion of their income at the gas pump than wealthier taxpayers. For Democrats, the passage of regressive taxes is always problematic. Today’s inflation and currently high gas prices are adding rigidity to Democratic resistance.

So, where else can funds be found? Republicans believe there are large sums of unused money, e.g., from the $1.9 trillion American Recovery Plan Act passed in March, floating around federal agencies. Democrats argue that these funds are needed by state and local governments and have been factored into their budgets.

Two significant problems have cropped up in recent days. First, the Democrats are unwilling to tap into certain potential funding sources for the infrastructure bill because they want to use them to fund the $3.5 trillion reconciliation bill they’re hoping to pass.

It’s being reported that the Democrats will be proposing—or at least considering—a carbon border tax. The tax is also being considered by the European Union in its new plan to address Earth’s warming.

As described by Elena Sanchez Nicolas:

…the levy - officially known as the Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM) - aims to accelerate global climate action and, at the same time, prevent businesses from transferring production to non-EU countries with less strict climate rules - dubbed ‘carbon leakage.’

Although the White House has indicated general support for what they’re calling a polluter import fee, no other accounting has been offered. What is known is that negotiations on the fee both in the US and the EU will prove difficult.

Senate Majority Leader Schumer intends to start debate on the infrastructure bill even before its written. Republicans are balking under pressure and have threatened to block any effort to pass an unfinished piece of placeholder legislation while negotiations are still underway.

Schumer and the White House are in an awkward position here because the current plan is to have the Senate pass an infrastructure bill as a regular order of business, in which case it requires a super-majority of 60 votes.

Why 60? Enter our friend, the filibuster stage left. Although it takes a simple Senate majority to pass the bill, 60 votes are required to close the debate to have it called for a vote. Let’s do the math once more. The Democrats only control the Senate if there’s a 50-50 tie for Vice President Harris to break.

Should the infrastructure bill lose Republican support, the only option for the Democrats would be to add it to the reconciliation bill. It would prove problematic as it’s unclear that Schumer can count on moderates like Manchin (D-WV), Sinema, and Tester (D-MT) to pass the bill.

The upcoming vote on the $3.5 trillion budget resolution agreed to by Schumer and Budget Committee Chair Bernie Sanders (I-VT) may provide the tell as to the intentions of the three moderates, as well as of the House progressives. The resolution is a sketch of what the federal government should spend and take in revenue the next fiscal year, tracked out over 5 or 10 years.

A budget resolution is a statement of the majority party’s program priorities. However, it’s non-binding and doesn't require the president's signature. Both the House and Senate need to approve it, however.

A resolution also instructs the subject matter authorising committees, e.g., energy, environment, tax. A budget resolution cannot be filibustered; it needs only a simple majority of 51 votes in the Senate and 216 votes in the House—four less than the number of Democrats.

It’s expected that the House will also pass the $3.5 trillion resolution. Sanders has been quoted extensively as comfortable with the amount, notwithstanding it is being $1.5 trillion below what he had initially hoped. Although House progressives are free to take their own stance on it, Sanders’s approval will count heavily.

Moreover, Speaker Pelosi has also indicated support for the amount calling it: a victory for the American people, making historic, once-in-a-generation progress for families across the nation. It should be remembered that the reconciliation bill will include more than Biden’s proposed climate plan, e.g., a Clean Electric Standard. Also included will be the President’s initiative to expand the definition of infrastructure to include societal elements like affordable senior care.

Trust levels between Republicans and Democrats remain low. There is, in essence, a game of political chicken being played on Capitol Hill. Who will flinch first is the question?

Democrats can’t count on the eleven Republicans working on the bipartisan bill. Senate Minority Leader Mitchell (R-KY) and Trump’s golfing buddy Senator Graham (R-SC) continue to grumble about the efforts of the Democrats to play both the reconciliation and infrastructure bills.

Several weeks ago, President Biden’s misspoken statement that he wouldn’t sign the infrastructure bill unless the reconciliation bill were also passed created a Republican furore. Although Biden retracted his threat, congressional Democrats continue to connect the future of both bills—a fact not lost on the Republicans.

Voters want and need the nation’s infrastructure upgraded. Although the politics of the infrastructure bill are complicated, it has going for it the support of voters, as shown earlier in Figure 1.

A bipartisan infrastructure bill would be of historic significance at a time in America’s political history that everything from mask-wearing to repaving the nation’s roads and repairing seriously weakened bridges has become partisan. After years of haggling over infrastructure repairs and expanding access to the internet, voters are likely to take it out on their senators and representatives in 2022. In the meantime, it’s hoped that members of Congress will spend more time working through their differences than pinning the blame on their party opposites.

Energy Voices is a democratic space presenting the thoughts and opinions of leading Energy & Sustainability writers, their opinions do not necessarily represent those of illuminem.

illuminem briefings

Carbon · Environmental Sustainability

illuminem briefings

Carbon Regulations · Public Governance

illuminem briefings

Climate Change · Environmental Sustainability

Politico

Climate Change · Agriculture

UN News

Effects · Climate Change

Financial Times

Carbon Market · Public Governance