A luxury carbon tax to address climate change and inequality

· 10 min read

Just as there is income inequality, there is also inequality in greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions.1 This involves both the amount of emissions and the types of consumption activities that generate the emissions.

As reported by Oxfam, the world’s richest 1 percent emit about 50 tons (metric) of CO2 per capita, which is 30 times more than the poorest 50 percent and 175 times that of the poorest 10 percent.2 This disparity is true even within countries. In the United States, for example, the richest 10 percent emit over five times more per capita than the bottom 50 percent and about three times the national average. In China, the richest 5 percent emit almost four times the Chinese average.3

This higher level of emissions flows from a more carbon rich consumption lifestyle, much of which is not accessible to middle-class or poorer households. For example, a first-class airplane trip from Washington to Paris is estimated to account for the equivalent of 1.82 tons of carbon dioxide, which is more than four times the same trip in economy class4 and nearly 10 percent of the annual U.S. per capita GHG emissions. There are other high-carbon luxury products limited to the rich, such as high-end sports cars, super-yachts, multiple large residences, and private jet travel. Space tourism can now be added to this list,5 with Virgin Galactic looking to provide this opportunity to thousands of super-rich tourists.6 Looking forward, two factors point to the disturbing potential for more high-carbon luxury activities. First, the number of people with the financial ability to purchase carbon-intensive luxury items is growing: today’s 46 million millionaires are projected to total over 62 million by 2024.7 Second is the potential for market forces and technological innovation to create new elite high-carbon products, as illustrated by the emerging space tourism business.

Of course, modest and poorer households also generate greenhouse gases. Fossil fuels and their accompanying emissions are part of the livelihoods of millions of modest families in the United States and around the world. Even the world’s poorest households generate some GHG emissions for everyday activities such as food preparation and household heating.

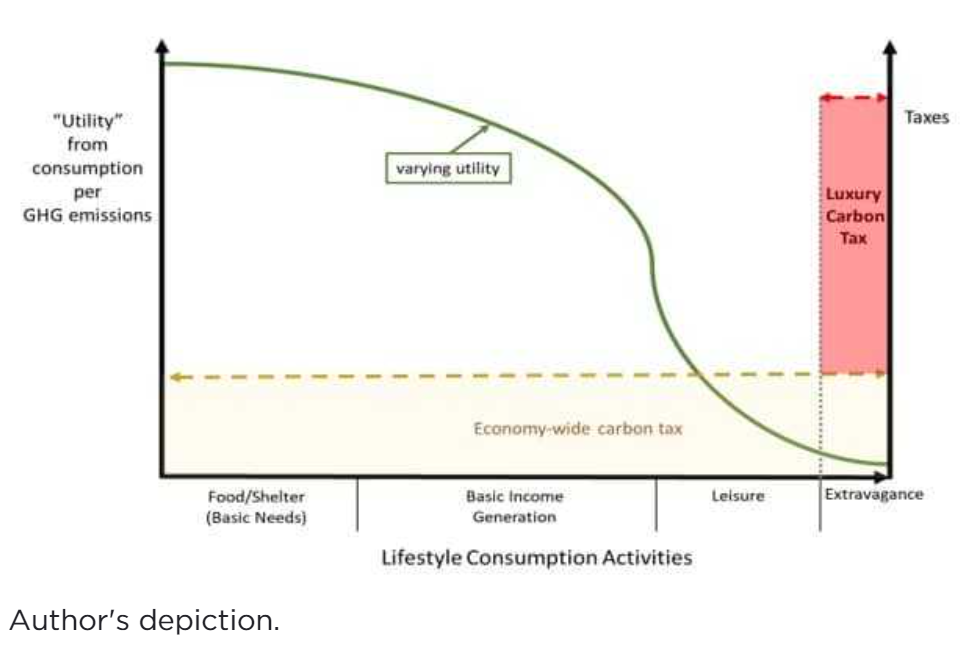

As these examples illustrate, not all emissions are created equal because the underlying consumption activities serve different purposes.8 This essay categorizes emissions into four types based on the underlying consumption activity: (1) for basic needs, such as food and shelter; (2) for basic income generation (such as commuting to work); (3) for basic leisure (such as going to the movies); and (4) for discretionary extravagant activities (such as space tourism). Similarly, the utility of the corresponding emissions also varies, arguably diminishing across these four groupings (as illustrated by Figure 1).

Figure 1: Different consumption activities have differing “utilities” and taxation regimes (illustrative)

Unfortunately, in contrast to the dynamics of economic wealth, where luxury expenditures can produce jobs and incomes for poorer working-class families, carbon constitutes, in simplified terms, a “zero-sum” game. We all share a total common carbon budget estimated at if we want to limit global temperature increase to 2oC.9 Basically, that is all the carbon that we can emit over the next several decades if we want to avoid significant global warming.10 We have even less to emit if we want to meet the more ambitious goals set out in the Paris Climate Agreement of “well below 2oC” and 1.5oC. When it comes to the climate, the more carbon that the rich emit for extravagant activities, the less room there is for others to emit for basic needs and other purposes.

Given these various factors, isn’t it reasonable to impose a special tax on the luxury emissions of the richest?

What might such a tax look like? We must first define two key elements: the products to be taxed and the price.

The proposed tax would apply to products that are both luxury items and generate substantial emissions, such as traditional high-end sportscars. By contrast, the tax would not target either the luxury $100,000 electric Tesla (what we might call “conspicuous consumption with a conscience”) or the working/middle class staple Ford pickup truck.11 The tax could operate at the time of purchase like a traditional sales tax. Alternatively, it could be charged periodically, for example annually for the registration of a high-carbon luxury vehicle. In either case, the tax would apply to products, as distinguished from a wealth tax, which is triggered by an individual’s status.

How much tax would be charged? The usual carbon tax approach is to apply a uniform rate based on the carbon content of emissions, which reflects the uniform climate cost of CO2 irrespective of where and why it was created. Three types of factors are commonly used to determine the appropriate rate: the social cost of carbon, the desired targeted level of emissions reductions, and the amount of revenues to be raised.12 This essay proposes a different approach for the luxury carbon tax. Rather than applying a uniform carbon price, a high and differentiated rate would be applied to luxury emissions.13 By way of illustration, each space tourism trip of $250,00014 could face a luxury carbon tax surcharge of $100,000 or more, while a lesser but still substantial charge would apply to first class air travel. This high tax rate is justified by various considerations, notably the detrimental societal impact of using up the common carbon budget for extravagant activities (akin to the reasoning underpinning excise taxes that target superfluous and damaging products). A high tax may reduce the demand for space tourism or alternatively encourage low-carbon innovation,15 both of which produce climate benefits. Moreover, the taxpayers in this case are rich consumers who can generally afford to pay the high rate or have the capacity to avoid the tax by seeking low-carbon alternatives—a preferable outcome from an emissions perspective.

The tax can be deployed as a complement to a traditional carbon tax (as illustrated in Figure 1). Alternatively, it could be implemented as the first step in a broader carbon pricing policy initiative. The revenues raised by the luxury carbon tax can be used like those from a traditional carbon tax; for example, to finance research and development into low-carbon solutions, to provide general budgetary support, or redistributed to taxpayers.

The tax would inevitably also present various challenges. For example, luxury taxes have faced implementation issues regarding the choice of products to be covered (including objections from targeted industries), the setting of rates, and enforcement. Carbon tax regimes also raise concerns, including the potential for unfair competition and carbon leakage with respect to other jurisdictions that do not impose a similar tax. Many of the issues facing the proposal presented in this essay have previously been encountered by luxury tax specialists and climate experts, which provides a body of experience and lessons from which to draw.

Though the overall impact of a luxury carbon tax would likely not be enormous, it would support several important policy goals simultaneously.

There has been a great deal of discussion about the potential of carbon taxes19 (including some with higher rates for luxury goods),20 in part because they are often viewed as an economically efficient climate tool. But there have also been concerns about its potentially disproportionate impact on poorer and middle-income households, in other words, that it is a regressive tax. This is in part due to the fact that poorer families generally spend a larger share of their income on gasoline and other items typically subject to a carbon tax.21 Although there are ways to counter-act this regressive impact, for example, by redistributing the revenues,22 the usual carbon tax remains burdened by its regressive characteristics. It was this concern about a disproportionate impact on the working class that in part catalyzed the yellow vest demonstrations that rocked France when a carbon gasoline tax was proposed.23

The luxury carbon tax, in contrast, is progressive since it is paid essentially only by the wealthy and so has a greater proportional impact on higher incomes. Given this context, formulating a luxury carbon tax can perhaps help to overcome some of the populist reservations and resistance to carbon pricing as a climate tool. Moreover, the progressive nature of the luxury carbon tax can be enhanced if the revenues are used to benefit poorer families, either directly through distribution programs or indirectly by funding health or other social services for the poor—or, alternatively, by supporting the development of low-carbon products for poorer families.

As politicians debate the relative merits of a wealth tax and other similar fiscal measures that target the ultra-wealthy, it is useful to inject into those conversations the potential to deploy a tool that also serves climate goals. There are other options that can address both climate and inequality considerations. For example, exempting low-carbon assets under a wealth tax regime can be a pro-climate policy tool. However, one advantage of a luxury carbon tax is that, by its very name and terms, it is an instrument that targets carbon extravagance.

However, as with any policy proposal, this luxury carbon tax also presents risks. For example, it is important that a luxury carbon tax discussion not weaken a potentially successful effort at enacting a broader carbon tax that has a bigger emissions impact. The luxury carbon tax could also generate more intense objections in some quarters precisely because it targets wealthier households. These are risks that would need to be assessed and managed.

A luxury carbon tax is worth considering. It can help to reduce emissions, stimulate low-carbon innovation, raise revenues, and address concerns about environmental justice and broader inequalities. In some situations, it might also increase the political acceptability of an accompanying broader carbon tax proposal. The proposal in this essay is presented as a thought-piece, and more analysis is needed before this idea can be transformed into a mature policy proposal—but it is a concept that merits additional consideration as an avenue to integrate equities and climate goals.

This article is also published on Ethics and International Affairs. illuminem Voices is a democratic space presenting the thoughts and opinions of leading Sustainability & Energy writers, their opinions do not necessarily represent those of illuminem.

illuminem briefings

Public Governance · Sustainable Mobility

Jesse Scott

Carbon Market · Carbon Regulations

illuminem briefings

Architecture · Carbon Capture & Storage

The Wall Street Journal

Carbon Market · Corporate Governance

Financial Times

Carbon · Corporate Governance

Trellis

Carbon Market · Carbon