· 9 min read

"We’re not a cheap date; the House is going to do what we have to do."

Jim McGovern (D-MA)

While the Senate fiddles over infrastructure and budget reconciliation legislation, the House burns. Seethes is perhaps a better word. I’ll explain why in a moment. First, I’ll set the stage for that discussion.

The Senate is currently in the process of trying to hammer out two critical climate-related pieces of legislation. The first is all about jobs and updating and repairing roads, bridges, and other essential services, including getting quality internet services to all Americans.

The second is a totally partisan piece of legislation termed budget reconciliation and carries a price tag of $3.5 trillion. Although the focus of this second article in an occasional series on US climate policy is reconciliation, it is impossible to provide a picture of what’s going on without discussing the interplay between the two bills.

A stage is set– reconciliation

Briefly, the infrastructure bill is about jobs and updating and repairing roads, bridges, and other essential services, including getting quality internet services to all Americans. Although there are climate-related elements, e.g., electrification of school buses, currently in the bill, the main thrust of the Biden climate plan will be through the reconciliation package.

The reconciliation bill covers more than climate change. For example, it will include a substantial increase in Medicare coverage for dental, hearing, and vision. Increased coverage has been a top priority of Senator Bernie Sanders (I-VT), Chair of the Budget Committee. The Committee is responsible for putting together a budget resolution, which opens the door to the actual bill.

A budget resolution is a statement of the majority party’s program priorities. However, it’s non-binding and doesn’t require a president’s signature. Both the House and Senate need to approve it, however.

A resolution also gives instructions the subject matter authorising committees, e.g., energy and environment. A budget resolution cannot be filibustered; it needs only a simple majority of 51 votes in the Senate and 216 votes in the House—four less than the number of Democrats.

As reported, the central climate provisions of the reconciliation bill will be:

- Achieve 80 percent clean electricity and 50 percent economy-wide carbon emissions by 2030.

- Provide funding for a clean energy standard, clean energy and vehicle tax incentives, climate-smart agriculture, wildfire prevention, federal procurement of clean technologies, and the weatherisation and electrification of buildings.

- Set new methane reduction and polluter import fees to increase our emissions reductions.

It appears now that a Civilian Climate Corps reminiscent of the Depression Era Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) will also be included. The CCC is considered one of the most successful New Deal programs. The modern national and state park systems have the Corps to thank for planting three billion trees and constructing trails and shelters in more than 800 parks nationwide during its nine years of existence.

The President initially proposed the Climate Corps as part of the infrastructure bill. As the proposed $2 trillion infrastructure plan was whittled down to $1.2 trillion, the Corps, along with other programs, will now have to be reckoned with as part of the reconciliation package. Once in service, the new CCC will undoubtedly plant trees, help communities reduce their carbon footprints, adapt to climate changes that are already occurring, and become more resilient in the face of future threats.

The rules governing budget reconciliation are arcane. It’s up to the nonpartisan Senate Parliamentarian to interpret and apply them. The filibuster-proof procedure was used to pass President Biden’s $1.9 trillion COVID relief bill in March. The Republicans used the process to enact their 2017 tax cuts.

Budget reconciliation is not a substitute for the regular order passage of legislation. It can be used only a limited number of times and for limited purposes.

The Parliamentarian has already ruled that the Democrats have only one more shot for achieving their policy priorities this year through reconciliation. It’s unknown whether they will have any opportunities in 2022. In any event, it would require a new resolution.

The Senate Parliamentarian has yet to rule on the guts of the reconciliation bill. As well, the Democrats are far from having one mind on what the legislation should contain. In part, its contents will be a function of what’s left out of the bipartisan bill, e.g., the Civilian Conservation Corps, assuming there is one.

Until more is known about the infrastructure bill, the climate-related contents of the reconciliation package will remain in flux. Moreover, there’s haggling going between House and Senate Democrats, as well as the White House.

The interplay of the infrastructure and budget reconciliation bills

Because the Senate is the more challenging body to get both the infrastructure and reconciliation bills through, it’s received much of the attention on and off Capitol Hill. However, it would be a critical strategic mistake to assume the House is happy with the situation.

As Representative Jim McGovern (D-MA) has said, the House is not some cheap date and will do what it feels it must. McGovern is Chair of the powerful House Rules Committee. The Committee is the nexus through which special legislation like reconciliation makes its way to the House floor for debate and passage.

Representative Ocasio-Cortez and other progressives are promising to sink the infrastructure bill should Senate Democrats not deliver on the reconciliation bill. Coupling the bills in the sense that “you won’t get yours if I don’t get mine” is problematic for both Republicans and some moderate House members.

Recall that several weeks ago, President Biden triggered Republican furore when he said he wouldn’t sign the infrastructure bill unless the reconciliation bill were also passed. At the time, it threatened the continuation of any further bipartisan discussion. Biden retracted the statement almost immediately, and the dialogue continued.

Although the President said, “oh, never mind,” Democratic House members said, “just a minute.” Republicans recognise that House progressives are doing what Biden said he wouldn’t.

Also eating at House members—moderate and progressive—is the seemingly total disregard of legislation they’ve already written—and, in some cases, passed and awaiting serious Senate consideration. Feelings run deep here.

As reported by Politico, Representative DeFazio (D-OR) scorched the Senate’s bipartisan infrastructure negotiations during a private call, saying he hopes the talks fail. DeFazio is Chair of the House Transportation Committee.

DeFazio finds the Senate proposals far inferior to his own bill that has already cleared the House. His bill, for example, provides $30 billion in climate-related provisions. The Senate bill has only $18 billion. DeFazio is not alone in his disdain for the current Senate discussions.

It’s critically important for climate activists to understand what policies and programs are possible under reconciliation. According to the House Budget Committee, only policies that change spending or revenues can be included.

Some items like Social Security cannot be changed by reconciliation, but Medicare can. It’s how Sanders expects to expand the program in ways mentioned earlier.

A national clean energy standard (CES) approaches the problem of reducing greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions from the electric power sector differently than a regulatory regimen like President Obama’s Clean Power Plan (CPP). Under the CPP, the federal government assigned emission reduction targets for each state through a rule-making.

With a CES, the federal government tells the electric sector that X percent of their electricity must be generated from carbon-free sources. The percent is increased over time until some desired endpoint is achieved. The Biden administration talks of two targets—100 percent carbon-free power by 2035 and an interim target of 80 percent by 2030 (80x30).

The payment-penalty model impacts both spending and revenues, so it’s expected to meet the reconciliation rules. However, that will be for the Senate Parliamentarian to decide.

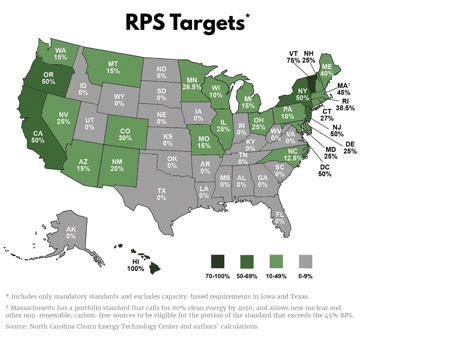

Support for a CES is not just because of budget reconciliation. It’s a policy that has gained currency as an alternative to a national carbon tax. There’s a familiarity about it, as it’s similar to the Renewable Portfolio Standards (RPS) that states have been using for some time. (See Figure 1)

According to the think tank Third Way, 27 states and the District of Columbia currently have a binding, share-based Renewable Portfolio Standard (RPS) in place, with an average requirement of 26 percent renewables and an average target year of 2022.

One of the prime benefits of a CES is its welcoming of any carbon-free power source, as well as carbon capture and sequestration (CCS). Its openness is also its political weakness. Many progressives are opposed to nuclear power and the pairing of natural gas with CCS. Senator Tina Smith(D-MN), a strong climate advocate, believes that such pairings will keep Senator Joe Manchin (D-WV) on board with the reconciliation approach.

Manchin has still not said how he’ll vote on the budget resolution or the reconciliation bill. Although he’s said he has some concerns, he’s never indicated what they might be—beyond the doing away of fossil fuels. Manchin represents a coal mining state and has reportedly made a lot of money being a part of it. s a consequence many climate activists are suspicious of him.

Manchin has been quoted as saying that eliminating fossil fuels wouldn’t help fight global heating—if anything, it would only make it worse. It’s a position that’s hard to reconcile with science and the promised priorities of President Biden and a large majority of his congressional colleagues.

It’s still unclear whether moderates like Senators Manchin, Tester (D-MT), and Sinema will run with the pack—when all is said and done. Both Schumer and Pelosi have their hands full trying to keep their caucuses in line enough to pull either or both the infrastructure and reconciliation bills across the finish line and onto President Biden’s desk.

If tensions between and within the parties were not already taut enough, Senate Majority Leader Schumer kicked the game of chicken he’s playing with Republicans up a notch or two by his call to begin the debate on a bipartisan bill yet to be written.

The manoeuvre is not as strange as it might appear. The debate would begin on any of the infrastructure bills that have passed the House. The bills would only be placeholders for what’s to come from the Senate negotiators. Once the bipartisan bill was ready, the House bills would be swapped out

Senator Susan Collins (R-ME), a co-author of the bipartisan bill, is respected and trusted on both sides of the aisle. She said of Schumer’s move: There’s absolutely no reason why he asked to have the vote tomorrow, and it does not advance the ball. It does not achieve any goal except to alienate people.

For Schumer, there was a goal other than alienating his Republican colleagues. Both he and the White House have taken flak from progressives for not moving faster on the President’s agenda.

It was a show of force—although a hollow one—on the part of the Majority Leader. The vote was destined to fail; it did by a vote of 49 to 51. Sixty votes were needed to pass.

It’s unlikely that the manoeuvre did any real damage. Following the vote, Senators Romney and Portman indicated the bipartisan group would have a bill ready for primetime somewhere around July 26th. The world waits.

Now that the infrastructure bill won’t be debated for days, what’s next?

Schumer also set the deadline to have the budget resolution ready for July 21st. House progressives have similarly pressed him to move the resolution if the infrastructure bill was still being negotiated.

Without knowing more of the details of the infrastructure bill, e.g., programs and funding sources, it seems premature to begin the reconciliation process. Moreover, it is unclear whether Senate Majority Leader Schumer has the 50 plus one votes needed to pass the resolution.

If it all sounds messy, it’s because it is.

Energy Voices is a democratic space presenting the thoughts and opinions of leading Energy & Sustainability writers, their opinions do not necessarily represent those of illuminem.