Fit for 55: The EU’s new climate targets and the EU ETS

· 8 min read

The European Green Deal presented by the European Commission on 11 December 2019 sets the goal of making Europe the first climate-neutral continent by 2050. The EU has once again taken the lead among major greenhouse gas emitters with the announcement of tightening climate targets and measures on 14 July 2021. The ambitious programme aims to reduce emissions by 2030 drastically.

Following the decisions at EU level in mid-July 2021, here is the second part of our series on the proposed changes to the European climate strategy and the impact on the EU Emissions Trading Scheme (EU ETS). The European Commission’s “Fit for 55” package might bring the goal of reducing greenhouse gases by 55 percent until 2030 compared to the reference year 1990 within reach. Now the package of measures faces months of negotiations between the 27 EU countries and the European Parliament.

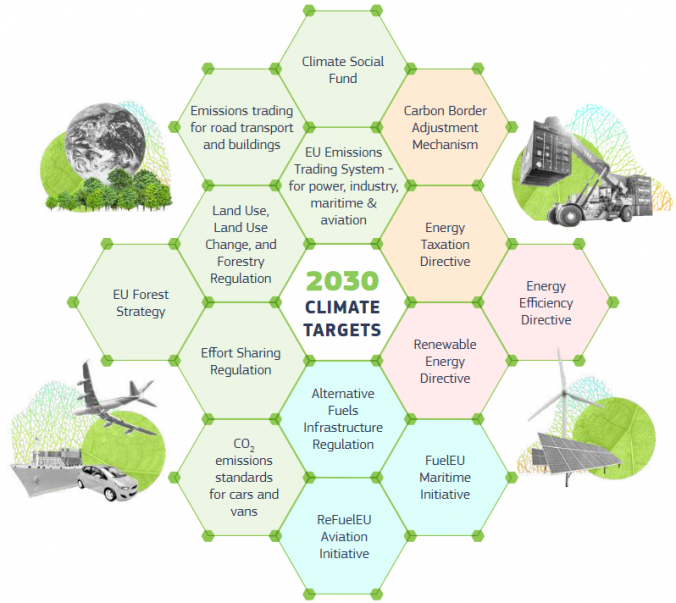

The package of over 10 cross-cutting legislative proposals includes eight revisions to existing legislation and five entirely new proposals, as Figure 1 (Source: EU Commission) depicts.

The ambitious targets are initially formulated in an open-ended way, leaving open some measures for the concrete implementation of the targets. In the following, we look at the changes to the existing emissions trading system (EU ETS), the planned new emissions trading system for road transport and buildings, the controversial Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM) and the new CO2 standards for vehicles.

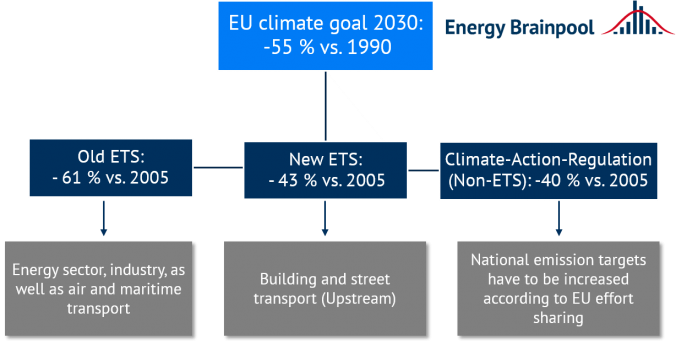

The existing EU ETS system covers about 40 percent of total emissions in the EU. The ETS has proven to be one of the most effective instruments for decarbonisation. Its extension to other emission-intensive sectors, such as aviation, has increased its effectiveness. In the drafted version of the “Fit for 55” package, the aim is to further increase the share of EU emissions within a regulated trading system. In the EU Emissions Trading Scheme for power generation, industry, maritime and aviation (EU ETS I), the emissions covered by this scheme are to be reduced by 61 percent by 2030 compared to 2005, instead of 43 percent as before. In addition to power generation, industry and aviation, shipping will now also be included from 2026 under the EU Commission’s proposals. A stricter reduction factor of the cap on emission allowances of 4.2 percent per year has been set from 2024, and the cap is to be lowered once by 117 million CO2 allowances.

Similar to the German national emission trading system, an ETS for the road transport and buildings sectors is also to be introduced from 2026. As the two sectors account for 22 percent and 35 percent of EU emissions respectively, their decarbonisation is essential for achieving the EU’s climate targets. Emissions covered by the EU Emissions Trading Scheme for Road Transport and Buildings (EU ETS II) should be reduced by 43 percent by 2030 compared to 2005. The amount of allowances to be issued annually will be reduced according the reduction factor of 5.15 percent to 5.43 percent per year.

At the same time, the sectors of buildings and road transport are to continue to be included in the Climate Action Regulation. National states must therefore continue to drive forward their own emission reduction targets and their implementation in the two sectors. Figure 2 shows the different reduction targets in the existing and the new EU ETS, as well as under the Climate Action Regulation.

In the ETS for transport and buildings, there will be no grandfathering and thus no free allocation of allowances. Similar to the established EU ETS, an market stability reserve (MSR) is to be introduced to remove unused allowances from the market. 25 percent of the revenue from the new allowance trading system will flow into a newly established social climate fund. The money from the social climate fund is to support socially weaker citizens and companies in the renovation of buildings and the purchase of environmentally friendly cars. Furthermore, the fund will make temporary lump-sum payments to socially vulnerable households to compensate for the increase in fuel and heating oil prices.

The “Fit for 55” package also provides for an EU-wide minimum tax rate based on energy content on polluting aviation fuels such as paraffin as well as on polluting boat and ship fuels from 2023 onwards, except pure cargo flights. The idea of a paraffin tax on intra-European flights is, in principle, a good instrument for effectively combating unnecessary air travel, but it disadvantages countries on the periphery of Europe, which, in contrast to the countries of Central and Western Europe, do not have a sufficient infrastructure network.

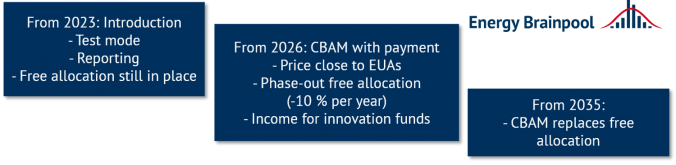

Starting in 2023, a carbon border adjustment mechanism (CBAM) is to be introduced with a transitional period of three years until 2026. The CBAM corresponds to a kind of climate tariff and needs to be paid by importers of products that were produced outside the EU in a carbon-intensive manner. This controversial mechanism is intended to ensure a level playing field for EU companies vis-à-vis companies from other economic areas and thus compensate for a competitive disadvantage that EU companies could suffer as a result of the tightened climate targets.

Through the CBAM, emission-intensive imports are to be levied, based on the price in European emissions trading. Initially, the CBAM will be applied only to selected goods, including cement, iron and steel, aluminium, fertilisers and electricity. The importing companies will then be obliged to buy CBAM certificates, the price of which will be equal to that of the certificates in the existing EU ETS for power generation and industry. However, the current design is criticised of being too bureaucratic, as a new CBAM authority needs to be established. Figure 3 depicts the proposed timeline for the introduction of the CBAM.

This CBAM is intended to prevent “carbon leakage”. Carbon leakage refers to a situation where there is a shift of carbon dioxide emissions to third countries outside a region with stronger climate ambitions, in this case the EU. The CBAM can be used as a means of pressure to get less ambitious countries and companies to do more climate protection if they want to sell their goods into the EU. However, this coercion towards more climate protection is difficult to design and administer in accordance with international trade rules of the World Trade Organisation. This could lead to retaliatory measures by other trading partners.

At the same time, the introduction of the CBAM is intended to gradually replace the allocation of allowances to European industry, which has so far been partly free of charge. Thus, the number of freely allocated CO2 certificates is to decrease by 10 per cent annually from 2026 onwards and to expire completely in 2035. Industries claim that this would put companies that export products out of the EU at a disadvantage and could induce carbon leakage, as EU-companies would then have to pay the CO2-price in the EU ETS. Figure 3 depicts the CBAM timeline.

The news that has been discussed most in the media is the target to reduce emissions from new vehicles by 55 percent by 2030 and 100 percent by 2035. However, due to technical and economic difficulties of the manufacturers, a loophole remains: the regulation on zero-emission vehicles could be postponed to 2040. In general, as things stand today, this measure means increased electrification of transport and the end of the age of conventional combustion engines. Some vehicle manufacturers are already planning to completely dispense with combustion engines by 2030 or at least to sell all their vehicles in electric versions as well.

However, such electrification has far-reaching implications to ensure continued grid stability and security of supply. This can only be achieved with an expansion of flexibility options on the part of the electricity grid and market, as well as a very strong increase in carbon-free generation options. Furthermore, uniform regulations must be enacted regarding bidirectional charging so that electric cars can also serve as storage. In order to ensure grid security and security of supply in the future, electricity grids must become intelligent so that they can react individually depending on the feed-in or load situation. This should happen in interaction with smart meters and the necessary communication technology, which would have to be installed in every household.

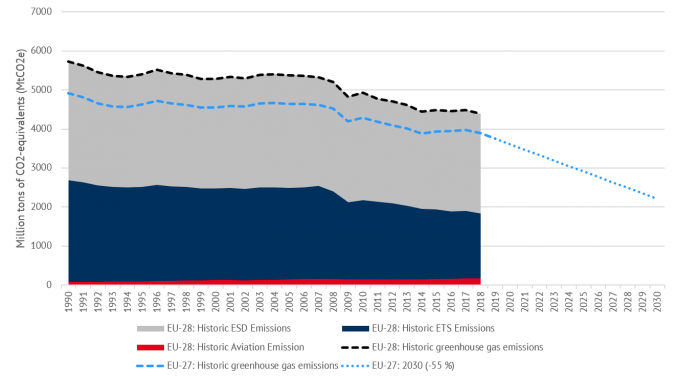

In summary, the changes to emissions trading in the “Fit for 55” package are a correct and important step by the EU towards greenhouse gas neutrality. In combination with the increased targets in the Renewable Energy Directive (40 percent of final energy consumption instead of 32 percent by 2030), energy efficiency and also a target of 310 million tonnes of annual negative emissions from CO2 sinks in the LULUCF sector (land use, its change and forestry), the European Union can thus take a progressive lead in reducing global CO2 emissions (see Figure 4, source: EEA).

However, the climate package is not yet binding legislation. The timetable for the entry into force of the final regulations at the end of 2023 and the end of 2024 is still some time in the future, despite the climate policy necessity. Yet, it is ambitious due to political inertia and the discussions on the EU level that follow now. In order to realise the new ambitious goals in the proposals of the new climate package, they must not be watered down or further delayed in the negotiations and legislation that now follow in the individual member states.

Also, the principle of climate justice has to become a focus so that a climate-neutral Europe is achievable for all social classes. Finally, there is a need for a detailed master plan with corresponding regulations to promote key technologies with which climate neutrality can be implemented step by step and beyond the 2030 targets.

More information and details on carbon trading, the climate package and the changes in the market are available in our live online training “The European CO2 Market: Insights and Outlooks” on 21 and 22 September 2021 (an English training is available on demand).

This article was co-authored by Christoph Kellermann, Lun Zhou and Simon Göß.

This article first appeared on Energy BrainBlog. Energy Voices is a democratic space presenting the thoughts and opinions of leading Energy & Sustainability writers, their opinions do not necessarily represent those of illuminem.

Aaron Bruckbauer

Pollution · Greenwashing

Jesse Scott

Carbon Market · Carbon Regulations

Glen Jordan

Sustainable Lifestyle · Sustainable Living

Inside Climate News

Pollution · Nature

The Jerusalem Post

Biodiversity · Climate Change

earth.com

Climate Change · Effects