· 20 min read

Some carbon removal startups currently partner with, or are considering partnering with, fossil fuel companies to accelerate scaling. However, such partnerships pose serious risks to the reputation—and therefore the ability to scale—of the carbon removal industry. They create serious moral hazards and can lead to other negative outcomes for the startups themselves. Those working in carbon removal have the opportunity to publicly reject these alliances, which would mitigate risks to the industry, strengthen the broader fossil fuel delegitimization effort, and fortify the industry’s place in the environmental movement.

The necessity of CDR

Carbon dioxide removal (CDR) is a suite of pathways involving large-scale human intervention to directly reduce the atmospheric concentration of carbon dioxide. The pathways range from enhancing the uptake of carbon dioxide by agricultural soils to directly separating carbon dioxide from the air using direct air capture machines and beyond. Each pathway has its own advantages and disadvantages in terms of energy use, land use, societal impacts, storage duration, and geographic compatibility. CDR is distinct from traditional emissions mitigation measures, such as solar panels or electric vehicles, as it can directly reduce the atmospheric concentration of carbon dioxide rather than merely slow the rate at which we are adding to it.

Most mainstream climate models and scientists now suggest that society will require massive amounts of carbon removal, ranging from a few to dozens of billions of metric tons per year, to achieve agreed-upon warming targets. According to Dr. Zeke Hausfather, CDR may be necessary to compensate for residual emissions from hard-to-abate sectors, balance out greenhouse gases other than carbon dioxide, reduce warming after exceeding global targets, hedge against the possibility of warming that is faster than expected, and extend the carbon budget for developing countries.

Paired with billions of dollars of investment and hundreds of millions of dollars in upcoming sales, there is little doubt that carbon removal is going to become an absolutely massive industry. The excitement in the community is certainly palpable. But carbon removal is situated within the broader carbon management ecosystem, which overlaps with a group largely responsible for the climate crisis: fossil fuel companies.

The fossil fuel legacy in carbon management

While approaches involving direct removal of greenhouse gases from the atmosphere have only gained prominence in the last several years, the related-but-distinct concept of point-source carbon capture as a concept has been around at least since the 1930s. Historically, much of the interest in the technology was driven by a desire to separate carbon dioxide and other impurities from natural gas as well as separation for injection into oil wells, known as enhanced oil recovery.

In recent years, carbon capture and storage (CCS), which involves capture and often geologic sequestration of carbon dioxide from industrial facilities for the purpose of reducing their emissions, has become viewed by some as another “tool in the toolbox” for mitigating climate change. The IPCC agrees to an extent.

However, the technology is often promoted by those in the fossil fuel industry, as it can provide a continued social license to operate for heavy emitters and paradoxically increase fossil fuel sales (extra fuel often must be burned to generate the energy needed for the capture system). CCS is decried by environmental groups that question its environmental and social merits and economic feasibility along with the motives of its proponents. It does not help that most CCS projects over the past few decades have failed.

The logic of CCS has now been extended by fossil fuel companies to atmospheric carbon dioxide removal technologies. Occidental Petroleum is planning to use direct air capture and geologic sequestration to offset the carbon dioxide emissions associated with the drilling, refining, and even combustion of the newly drilled oil, generating a commodity they have termed net-zero oil. Vicki Hollub, the CEO of Occidental Petroleum, stated:

We believe that our direct capture technology is going to be the technology that helps to preserve our industry over time. This gives our industry a license to continue to operate for the 60, 70, 80 years that I think it’s going to be very much needed.

This presents a clear moral hazard that I will revisit later.

Separately, various individuals have argued that the involvement of the carbon removal world with fossil fuel companies is inevitable for a particular reason: the similarity of the industries. Over four billion metric tons of oil are extracted each year, and some modeling scenarios call for over 10 billion metric tons of carbon dioxide removal each year. While much of this removal will occur through more natural means like afforestation that do not involve as much artificial equipment, the carbon removal industry will still need to move more mass than the oil industry in just a few decades.

Fossil fuel companies, the argument goes, are already in the business of managing large amounts of materials and fluids, and they possess the geologic modeling, drilling, pipeline, and engineering expertise along with the capital and political influence that could theoretically help scale carbon removal. While this is a seemingly logical vision, there are multiple issues to consider. The first is that many if not most carbon removal pathways, from enhanced rock weathering to biochar and beyond, are not actually compatible with or necessarily related to large-scale fluid management. The compatibility is primarily limited to direct air capture and geologic sequestration, which is only one of many CDR pathways.

Another issue with this argument is that fossil fuel companies actually make very little profit per metric ton of emissions for which they are responsible. This implies that they would likely not be able to afford large-scale carbon removal to cancel out their emissions even if they truly wanted to.

For example, Chevron earned $35.465B in 2022 but was responsible for 721.8 million metric tons of CO2-eq emissions that year. This translates to around $50 of profit per ton of CO2-eq emitted. Costs per ton for most legitimate and durable CDR approaches are and will remain higher than this value. Even with major emissions reduction initiatives, fossil fuel companies would only ever be able to use carbon removal to offset a very small fraction of their emissions without major impacts on their profitability.

Additionally, many of the supposed benefits can be found elsewhere. People and firms with the required expertise can be hired. Operating at scale is not unique to fossil fuels. Many actors have ample political capital they could lend to CDR. And the global economy and sources of capital are certainly much, much larger than merely the fossil energy industry.

Carbon removal startups should reject this overly optimistic vision and choose not to engage in partnerships with fossil fuel companies. The rest of this article defines the concept of “partnership” and explores how the costs of engagement with the fossil–industrial complex will likely be higher than the supposed benefits.

Defining corporate partnerships

What exactly is a corporate partnership? If a partnership were merely purchasing something, then any company, or person for that matter, that has ever purchased gasoline to transport something would be a “partner” of the fossil fuel industry. Clearly, this definition would be too broad to be useful or meaningful, and individualizing responsibility to customers for climate change is largely a reframing tool used by the industry to distract and shift blame.

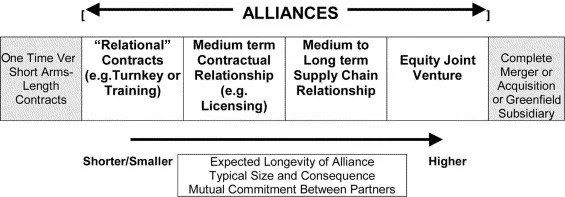

The below diagram from Contractor & Lorange can help clarify this issue:

Figure 1: The spectrum of business alliances

For the purposes of this article, a corporate partnership or alliance is defined as anything that involves a relationship that is to the right of one-time contracts in the diagram. This would include all formal alliances based on Contractor & Lorange’s definition along with mergers, acquisitions, and subsidiary relationships. Accepting investment in a fundraising round is also included.

This may seem like an arbitrary line. However, I believe it is reasonable as it includes most relationships that are generally considered to be partnerships without including one-time transactions that—like the gasoline example—may be impossible to avoid.

While one-time contracts must be permitted to allow the industry to function, it is probably still advisable to work toward alternatives. For example, some highly engineered carbon removal pathways depend on chemicals produced by petrochemical providers, which are often subsidiaries of fossil fuel companies. It may be necessary for startups commercializing such pathways to purchase these chemicals through one or multiple one-time contracts. These contracts would not be partnerships as defined here. However, to prevent the issues and risks discussed herein, it would still be advisable for these startups to either engineer a way around this dependence or seek an alternative supplier as soon as possible.

For the purposes of this article, “fossil fuel companies” are defined as organizations that receive the majority of their revenues from the extraction, refining, sale, lobbying on behalf, or advertising of fossil fuels. Many of the arguments presented here will not apply with as much force when potential partners only have very minor fossil interests.

Given this understanding of partnerships and fossil fuel companies, we can now investigate specific reasons why these partnerships should be avoided.

The 7 Partnership Pitfalls

1. Reputational Harm to CDR

Perhaps the most important reason that carbon removal companies should avoid fossil partnerships is the reputational harm they do to the broader CDR industry, paired with the risk of reifying the much-feared moral hazard. Much, if not most, of the resistance to carbon removal as a concept comes from the environmental movement, which should ostensibly support this technology class. While some organizations and nonprofits within the environmental movement improperly conflate CCS, CCUS, and CDR, the effect of their disapproval is the same in that it creates friction for deployment. And massive deployment is exactly what we need to meet Paris Agreement-mandated targets.

Much of the resistance is rooted in the concept of the moral hazard, which for CDR is the idea that a false promise of deployment will serve as both a distraction and a justification to continue operating and even expanding fossil infrastructure. There is also significant discussion around the direct risks posed to communities from the buildout of certain technologies, although these criticisms often focus a bit more on point-source capture schemes. A letter written by the Center for International Environmental Law and signed by over 500 environmental organizations is brutally critical of CCS and CCUS, although CDR does not escape scrutiny. While there are various problematic and sensational assertions in this piece and similar resources, partnering with fossil fuel companies is certainly not going to help make the case for CDR. And environmental organizations have real political power that should not be neglected.

To add to these grievances, there are already budding issues with public resistance to carbon removal and associated infrastructure. There was a recent protest of Planetary Technologies’ ocean alkalinity enhancement pilot in the UK. Some locals are skeptical of CarbonCapture’s upcoming Project Bison DAC installation in Wyoming. Politico recently noted that two environmental groups prompted the New Orleans City council to pass a ban on underground storage of carbon dioxide. The Politico article also notes growing opposition to a DAC project—one organized by a petroleum company, California Resources Corporation—in California. Some residents of Satartia, Mississippi, where there was a leak from a CO2 pipeline in 2020 with direct health impacts on locals, are now sharing their story to warn about the deployment of CO2 transportation infrastructure.

While it might be easy to chalk this opposition up to no more than misguided reasoning and hostile NIMBYism, it is much more than that. Those opposing these projects have real struggles and concerns that would be highly irresponsible to neglect, especially for an industry that seemingly wants to respect communities where it operates. Notably, some of the concerns revolve around the moral hazard created by CDR. Part of the initial pushback to Planetary’s UK project was related to the company’s offset-oriented business model. Resistance to individual projects—that may in reality have very low risk—can arise from more general resistance to the industry and the companies operating within it.

Partnering with fossil fuel companies will add fuel to the fire and make what is already a daunting task that much more difficult. Selling carbon removal offsets to fossil fuel companies might even be a direct manifestation of the moral hazard. Quotes like the one from Hollub, the CEO of Occidental Petroleum, prove the point even further. If we allow the promise of CDR to enable any degree of continued or expanded extraction of otherwise abatable fossil fuels, we will have created the moral hazard we are seeking to avoid. Early signals of a willingness to do this will only intensify the resistance to the technology.

2. Greenwashing and the Moral Hazard

Greenwashing occurs when organizations promote themselves as more environmentally friendly than they really are. It can be intentional or unintentional, although it is often part of a broader political project aimed at earning social license for activities that the public might not approve of otherwise. Fossil fuel companies could use a promise of carbon removal that may or may not materialize to gain this social license and justify continued operations that they may not have been able to otherwise, which is the moral hazard.

There is a sentiment in the carbon removal community that partnerships are fine as long as they are not explicitly used for advertising and greenwashing. However, cheesy ads from fossil fuel companies already discuss carbon capture, nature-based solutions, biofuels, and CCUS. While these ads are not necessarily reaching massive audiences, they are indicative of companies’ public positioning. Fossil majors already disproportionality tout low-carbon energy investments that are in reality a very small fraction of their overall capital expenditure. It does not require stretching one’s imagination to see how carbon removal could fall even deeper into this same category, even if individual companies would prefer for their own partnerships to not be promoted.

There have been some recent crackdowns on greenwashing, including a specific ban on certain advertisements from fossil fuel companies regarding their paltry investments in renewable energy. While these kinds of regulations will hopefully spread and have their intended effect, the carbon removal industry has the opportunity to avoid becoming a pawn for fossil fuel companies by avoiding and publicly rejecting partnerships with them.

3. Carbon Tunnel Vision

Let’s imagine for a moment that pairing carbon removal with oil production actually does work and that there are serious and enforceable government mandates ensuring that for each barrel of oil that is drilled, refined, and combusted, there is a corresponding amount of verified, long-term CO2 sequestration. In this very optimistic scenario, the climate impact of oil production and use truly would be canceled out, allowing continued use of the resource without its contribution to climate change. This scenario is not quite as desirable as it might sound.

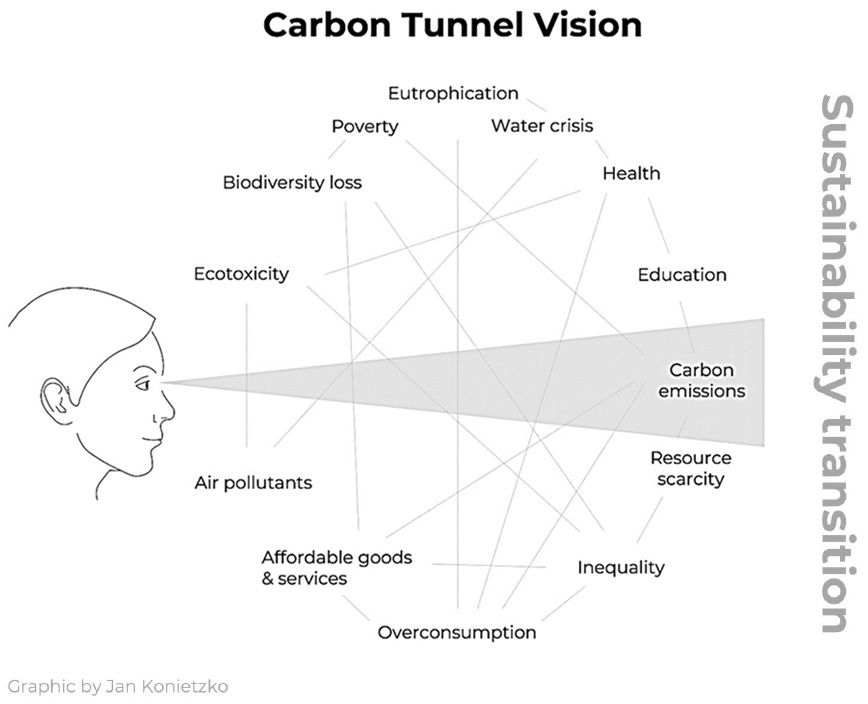

In 2021, Dr. Jan Konietzko published the below graphic summarizing the issue of carbon tunnel vision, where the attention of companies or other decision-makers falls primarily on carbon emissions at the expense of various other important social and environmental domains. Carbon tunnel vision is caused and exacerbated by the urgent nature of the climate challenge paired with a lack of systems thinking. While carbon emissions of course affect these other categories (more emissions will contribute to resource scarcity, biodiversity loss, and so on), there are plenty of other ways that industrial operations can exacerbate them.

Fossil fuels cause climate change, and this is perhaps their most significant negative effect on human well-being, given the sheer extent of current and expected damages and its interconnected nature. However, focusing only on emissions is clearly reductionist, given the numerous other human and environmental impacts arising from the extraction, refining, distribution, and use of fossil fuels.

Carcinogenic releases, funding of despotic regimes, mountaintop removal coal mining, poisoned wells, and oil spills are only just a small sample of the negative impacts that fossil fuels have on society. Various studies are beginning to estimate the true cost of fossil fuels on society inclusive of these other impact categories. We need to end fossil fuel use not just for the climate but for all other affected stakeholders as well.

Therefore, a moral hazard exists even in the optimistic scenario where carbon removal truly compensates for fossil emissions. Carbon removal companies should be highly cautious of engaging with a system where the technology could be used to extend the social license of fossil fuels and the negative impacts they have on society other than just merely greenhouse gas emissions.

4. Fossil Delegitimization and Environmental Coalition-Building

Our society is currently quite dependent, and some say addicted, to consuming fossil fuels. Transitioning away from them will take much, much more than an unlikely series of altruistic individual decisions, such as everyone choosing to stop driving. In Ending the Fossil Fuel Era, the editors note that a widespread and authentic delegitimization of fossil fuels is necessary. By this, they mean:

the reconceptualization and revalorization of fossil fuels or, to be precise, humans’ relations with fossil fuels. [This entails a] shift from fossil fuels as a constructive substance to a destructive substance, from necessity to indulgence ... from fossil fuels as that which is normal to that which is abnormal (12).

A significant part of the movement for climate action focuses on delegitimizing the fossil fuel industry to make way for the policies and investments to begin actually transitioning away from it. Tactics for doing this can vary significantly. Divestment, which was a tool helpful for pressuring the South African government to end apartheid, is a tactic commonly pursued by climate activists due to its potential for delegitimization. While the actual financial impacts of divestment vary, its mission goes beyond depressing stock prices or directly depriving companies of capital. It is part of a broader social campaign with the goal of influencing people to see fossil fuels in a new and unfavorable manner—one with which we should not want to be associated.

Budding carbon removal companies, as increasingly relevant and influential actors on the world stage, can play a valuable role in this process of delegitimization by simply boycotting alliances with fossil fuel companies. This practice could also help build stronger coalitions with the environmental movement, which would be highly valuable for achieving our shared environmental goals.

Many carbon removal advocates like to start presentations and pitches by saying that “rapid emissions reduction is needed and should come first.” Avoiding partnerships with some of the biggest emitters in the world would be an easy way for us to put our money where our mouths are.

5. Recruiting and Morale

To successfully realize the vision of the carbon removal industry, we will need massive amounts of talent. Tens of thousands of people with skills in engineering, chemistry, plant operations, business development, and so on will be required. Many of these people may transition from other industries, but many are only being trained now or may not even be in college yet. If the median age of people who will be working in carbon removal by 2050 is 30, that would mean that more than 50% of the ultimate workforce is currently under three years old or has not been born yet! I should start lecturing my nephews about techno-economic assessment now, I suppose.

According to polling conducted by Pew Research Center, younger Americans are far more in favor of ending offshore drilling and phasing out fossil fuels than their older peers. A poll by EY indicated that over 60% of Gen Z Americans find oil and gas jobs either somewhat or very unappealing. A number of young people intentionally avoid jobs related to oil and gas extraction, and even those working at oil companies have a series of complicated thoughts and feelings about their work. It is easy to imagine these trends continuing as the climate crisis worsens.

These cultural trends imply that active ties to fossil fuel companies could lead to significant and adverse impacts on both recruiting prospects and the morale of current employees at carbon removal startups. The impacts on recruiting may be felt more acutely when recruiting younger and more idealistic individuals and in tighter labor markets, but they will be present regardless. Oftentimes, those working at or joining new carbon removal ventures are themselves very “pro-climate” and skeptical of fossil fuels, which could be a recipe for cognitive dissonance and ultimately burnout or departure from companies with such partnerships. While there are probably many prospective employees who would not mind such alliances, the benefits are likely outweighed by the costs to the talent pipeline and current and future morale paired with the other reasons listed here.

6. Liability and Risk

The criticism and distrust of the fossil fuel industry derives from more than just its climate impacts; local pollution and impacts arising from spills, leaks, explosions, accidents, and so forth are responsible for much of the bad blood. Activists living in Louisiana’s “cancer alley” or Detroit’s most polluted zip code in the shadow of the Marathon refinery are quick to note the harmful impacts of their neighborhoods’ proximity to fossil fuel operations.

Sometimes, operators are held liable in the wake of these events. BP had to pay around $65 billion after the Deepwater Horizon incident, Exxon was ordered to pay nearly $1 billion for the Valdez oil spill, and Shell has had to make payouts in the tens of millions of dollars multiple times to communities in Nigeria due to past oil spills. There are numerous other recent and current examples of climate change-related litigation involving fossil fuel companies that could have significant impacts on the operations, reputation, and even finances of these actors. The first youth climate change trial in the U.S. kicked off mere days ago at the time of writing.

The message here is that partnering with these entities in a formal sense could pose direct liabilities and risks to the operation of a carbon removal business. Reputational risks would be more likely in the event of lighter-touch partnerships, but any level of combined operations could pose direct legal or economic risks to the company in the event of a spill, leak, accident, or other disaster. While it is impossible to avoid all risk in any kind of heavy industry, it is possible to minimize it by avoiding working with historically problematic companies and at higher-risk industrial sites.

7. Bias-Prone Pro-Partnership Arguments

The case for engaging with historically bad actors partially rests on the claim that projects will create more benefits than harm for society. This is certainly a valuable calculus, and, if we had a crystal ball showing that it would undoubtedly be true for a particular partnership, this should probably change our thinking, particularly if there were no negative impacts that fell on disadvantaged groups in this hypothetical situation.

However, when what is on offer from fossil fuel companies includes capital, prestige, and connections, it may be hard to assess the net benefits of the engagement in an unbiased way. It may be easy to trick ourselves into believing that the engagement is favorable. While it is difficult to admit, I have felt this pressure in my consulting work before. The allure of a highly paid contract with a prestigious company has a way of manipulating one’s logical faculties that cannot be denied. Ultimately, the project did not proceed, and I have now drawn a red line in terms of clients or partners I will accept. I hope this article can convince others to do the same.

A Structural View of CDR and Fossil Fuels

This is a contentious issue. I would like to emphasize that I do not believe that individuals who currently happen to work in the fossil fuel industry necessarily do so in bad faith. There are many good people who work in this industry, and many legitimately want the best for the climate and humanity. Most probably do.

The issue with fossil fuel I raise here is more of a systemic or structural one. Carbon removal startups in particular should avoid alliances with fossil fuel companies, as there are systems and structures in place that increase the probability of the moral hazard. These include the inherent incompatibility of fossil fuel extraction with climate action, the status quo of the fossil economy, the lobbying and influence apparatuses of the companies, and the fiduciary responsibility of the organizations to make profits for shareholders. Greenwashing, for example, is unsurprising when considering the cultural, economic, and political context in which fossil fuel companies exist. When thinking through the benefits and the avoided risk from not engaging with these structures in mind, I believe the choice becomes clearer.

This article poses a narrow critique and recommendation. There is less of a moral hazard created when renewable energy providers or carbon utilization startups partner with fossil fuel companies, as sincere implementation of these technologies can decrease fossil throughput. Carbon removal companies should definitely hire responsible and well-meaning individuals with oil and gas experience to help build out the industry. They should definitely work with most other kinds of established industrial and corporate structures as necessary to scale, as long as it is done responsibly and ethically. We probably should not judge carbon removal companies that engaged with these interests in the past, as long as the partnerships cease. Certain levels of interaction, such as purchasing diesel to operate a semi-truck, might be unavoidable in the short term. Serious partnership with these fossil interests, however, should be completely avoided for the good of the industry and, ultimately, society and the environment.