· 11 min read

The carbon markets are experiencing rapid growth. The voluntary markets are expanding due to unprecedented demand from corporate buyers and a related boom in issuing new credits. The compliance markets are growing via increased allowance prices and soon also through the emerging Paris Agreement market. All the while, the two markets are increasingly converging, and the voluntary market is bound to go through substantial changes. Will there be a competition between voluntary and compliance buyers for the same credits? The next years will show. Eventually, the carbon markets will become carbon removal markets.

Growing for different reasons

Both the voluntary and compliance carbon markets are growing. Based on the 2021 data, the voluntary carbon market size reached $1bn, while the compliance markets increased to $851bn. Even with a conservative estimate for the compliance markets – given the recent price fluctuations – the voluntary market accounts for 0.1-0.2% of the compliance and voluntary markets combined.

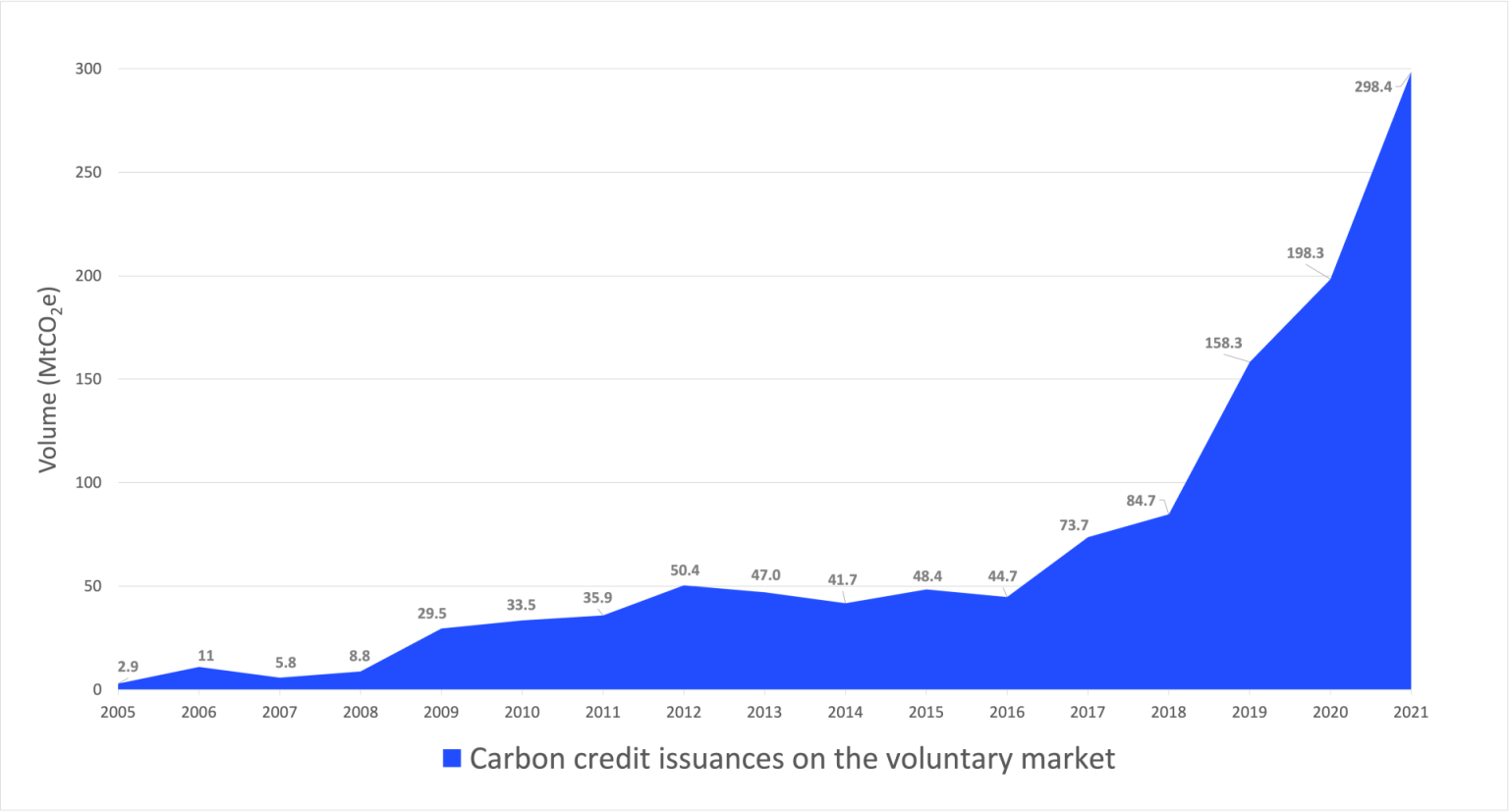

The drivers behind the growth in these two markets are different. The market size is calculated based on the number of carbon credits or allowances, multiplied by their price. The growth in the voluntary market was driven by an increase in the number of carbon credits to 300Mt CO2e, as seen below.

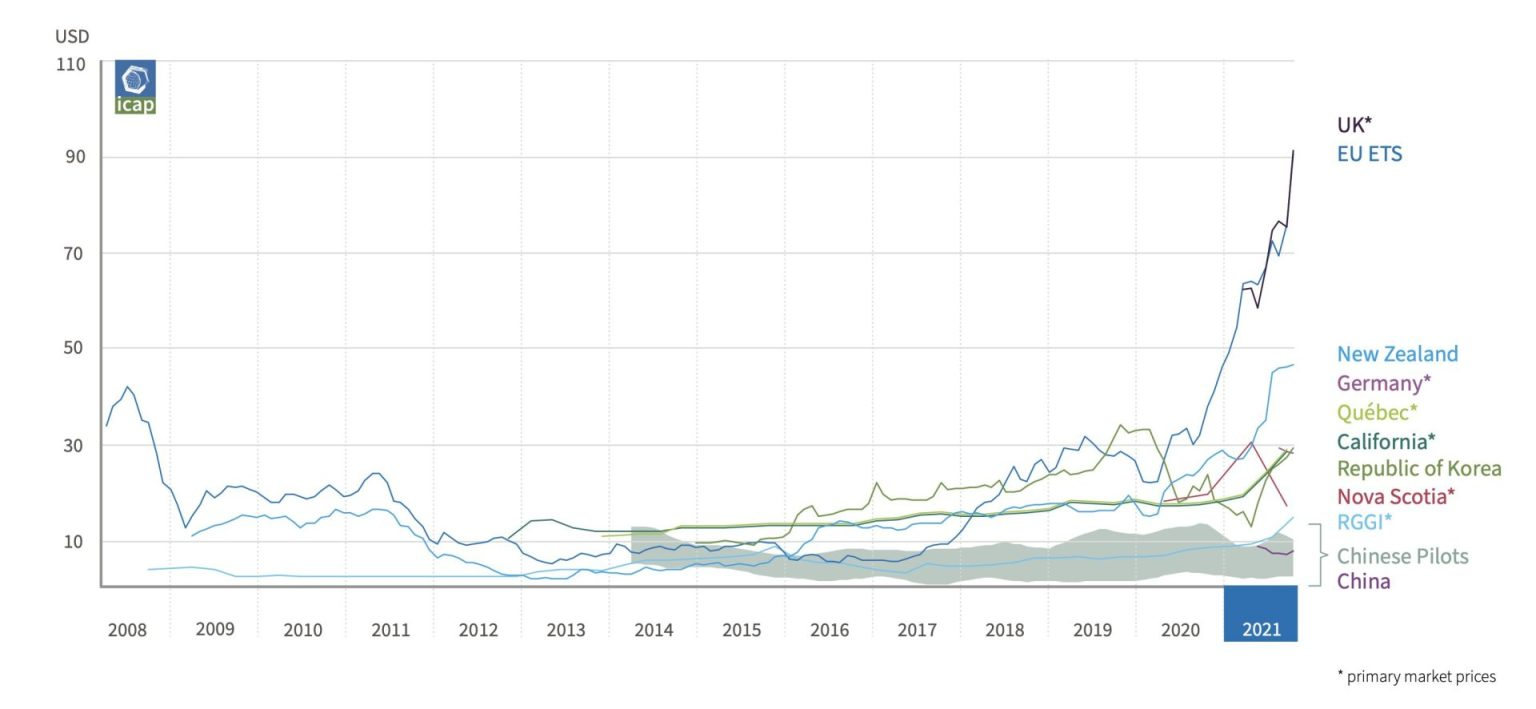

For the compliance markets, the driver of the 164% growth compared to the previous year has been the increase in the price of its carbon allowances. This has been driven by the world’s most established carbon market, the EU Emissions Trading System (EU ETS), which makes up 90% of the global value of the compliance markets today.

As of January 2022, there are a total of 25 emission trading systems in force that cover 17% of global emissions. The EU ETS stands out as a success story that has been close to 20 years in the making. Its decreasing cap keeps the upward pressure on allowance prices, pending the outcome of the ongoing review of the legislation. Currently, compliance markets consist of the emissions trading systems, and the recent ICAP report is a treasure trove of facts, graphics and analysis of the global progress in this space.

Comparing the market size only tells part of the story

Impact on reducing emissions

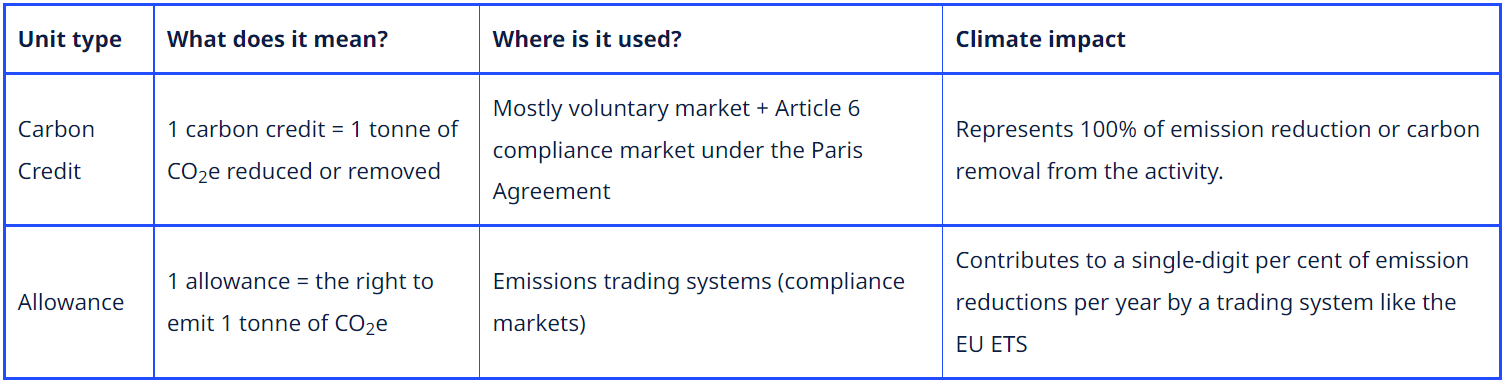

There is more nuance in comparing the size of compliance and voluntary markets than may seem obvious at first glance. As explained above, the market size is derived from the number of credits or allowances and their price. Both the baseline and crediting systems that use carbon credits, and emissions trading systems that use allowances, put a price on carbon. However, the climate impact of a carbon credit is different from that of an allowance.

Carbon credit reflects a 100% reduction or removal of greenhouse gases, whilst allowance provides the right to pollute in trading system that delivers a small percentage of real emission reductions. Hence, only a fraction of the $851bn compliance market size directly represents emission reductions.

A substantially simplified table above highlights the role of carbon credits and allowances in addressing climate change. One carbon credit equals one tonne of CO2 equivalent reduced or removed in the ideal circumstances that we should strive for with a laser-sharp focus. Unfortunately, there is an abundance of cheap low quality credits circulating in the voluntary market that don’t reflect such climate impact. Not all carbon credits are used as offsets; there are also other opportunities to leverage their impact.

The decreasing cap of the trading system and the resulting scarcity of allowances is what are expected to drive down emissions under the trading systems. For example, the companies covered by the ETS reduced emissions by about 35% between 2005 and 2019 – that is, on average, 2.5% per year. However, not all emissions trading systems are successful in delivering emission reductions, and not all emission reductions happen as a result of trading systems. Compliance markets don’t operate in isolation from other policies. Sometimes, other policy tools can be more successful in decarbonising different parts of the economy. It’s important to attribute the results to the policies that actually deliver these.

Impact on financing climate action

Another aspect is the financial flows that voluntary and compliance markets generate. When it comes to the voluntary market, the $1bn market size had an average price of carbon credit of $3.37 in 2021. This is clearly not enough to deliver high integrity climate projects. Besides the additionality-related challenges in the voluntary market, there’s also the pressing question around the money-making middlemen. It’s important that the projects deliver actual additional climate impact and that the funding reaches those on the ground.

By the end of 2021, emission trading systems raised $161bn cumulatively for climate action. The EU ETS has delivered the majority of it by raising $117bn in auctioning revenues. When compared to the market size of $851bn in 2021, one would expect that more money could have been put to purposeful use to date.

The two markets are converging

The voluntary and compliance markets are getting increasingly interlinked, and the lines between the two are blurring. This will lead to the voluntary market going through a major change and looking quite different by the end of the decade.

Today, the compliance markets consist of emissions trading systems. This is bound to change with the emerging compliance markets under the Paris Agreement. Article 6 of the Paris Agreement allows countries to collaborate in order to achieve their climate targets. This will increase the scope of compliance markets. Such cooperation can take different forms, from emission reduction and carbon removal projects to linking their emissions trading systems. Compared to the Kyoto protocol era, all countries are covered with climate targets under the Paris Agreement, and the trade with the international carbon credits under Article 6 will need to be transparently recorded to avoid double counting.

Compliance markets have been leveraging voluntary market credits and standards for quite a while. California’s emissions trading system and the offsetting scheme for international aviation allow the use of certain voluntary market carbon credits. The same goes for carbon taxes established in Colombia and South Africa. Using the infrastructure of the voluntary market in the context of the Paris Agreement compliance markets makes a lot of sense. Why spend resources to establish new standards and methodologies if one can use infrastructure that is already there? A good example here is the partnership between the Swedish government and the Gold Standard, where the plan is to use Gold Standard at least for part of Sweden’s acquisition of international units under Article 6. The Gold Standard has also established their Article 6 early mover programme.

“We’re entering a phase where the standards won’t just be used for the voluntary market but will be used by governments for compliance schemes and tax schemes. […] So rather than there being this isolation between the voluntary market and compliance markets, you have kind of this greater carbon credit, which can be used in all these different markets. And I think that’s good. That allows you to scale, because you’ve got all of these different uses that credits can be used for.”

Hugh Salway, Gold Standard, in an interview with GreenBiz, 2021

Another development to notice is the growth in the number of domestic crediting systems where governments set the rules for generating credits from domestic projects. This allows governments to guide investments to certain types of emission reduction or carbon removal projects and tap into the demand from corporate buyers without any of the challenges around international transactions where the implementation still needs to be put in place.

What about the timeline of the convergence of the voluntary and compliance markets? Seasoned carbon market experts suggest that the voluntary market might be absorbed by Article 6 market already around 2025.

Emerging competition

The rulebook for Article 6 that was agreed upon at the COP26 did not include explicit references to the voluntary market. However, it includes a crucial element where the governments, as gatekeepers, can decide whether they require voluntary market credits to be authorised and the country’s emission balance adjusted. Work on the further details of implementing Article 6 is ongoing, and further important details may emerge.

If the voluntary market starts catering for the compliance markets, the demand side expands, but the supply stays the same.

“Voluntary buyers are going to start competing with mandatory/compliance buyers, very possibly for the exact same offsets. The procedures to verify and issue carbon offsets to the voluntary or to the Article 6 markets may not be very different, and this is going to present some participants with an interesting dilemma.”

Alessandro Vitelli at carbonreporter.com, 2021

Such a development could lead to countries and their corporates chasing the same carbon credits. Governments have the upper hand in such competition. If they are keen to secure a supply of certain credits, they can regulate related activities, which would essentially nationalise the (part of or whole) project. To add to the uncertainty – this may happen at any stage of the ongoing project.

The end result of the level of convergence depends on decisions that have yet to be taken. One of the key elements is how widely governments require voluntary market projects to be authorised by them. The voluntary market actors can play a range of roles, but the government is the gatekeeper in the decision making.

Supply and demand

By 2030, estimates suggest that the voluntary market could scale to well over $100 billion per year. We established above that in addition to the corporate demand, there will be an increasing demand from compliance markets for voluntary market credits. It’s unlikely that the compliance market demand will reach the levels seen during the Kyoto era when participants of the EU ETS used over one billion tonnes of international credits in 2008-2012, mostly from the Clean Development Mechanism. After learning the lesson of the surplus this created in the trading system, the EU has since opted for domestic climate targets.

The majority of countries intend to use the Article 6 compliance markets to achieve their climate targets. It makes sense, given that the low hanging fruits in decarbonisation will be picked soon, and countries have very different emission reduction and carbon removal capacities. However, all countries have climate targets they need to meet, and any sold international credits require revising the national emission tally upwards to avoid double counting. This will make all countries cautious in their decisions to sell carbon credits.

Another potential source of demand from the compliance markets (for both voluntary market and Article 6 credits) is the offsetting scheme for international aviation (CORSIA). However, given the recent change in the baseline, the system might not generate much demand any time soon.

The challenge the voluntary market is currently facing is the supply of high-quality credits. The controversial news around the quality of offsets is driving corporates to find that middle ground that can be transparently confirmed as not greenwashing, but that still includes a price per ton that the boards find reasonable.

The future of the voluntary market depends on how well it is structured and governed. The Integrity Council for the Voluntary Carbon Market is working to accelerate the growth (supply), and the Voluntary Markets Integrity Initiative focuses on participation and demand. These and other organisations can help create a quality supply of credits, a deep and liquid market and add to the transparency.

Carbon markets will become carbon removal markets

Looking further into the future, carbon markets will eventually become carbon removal markets. This is, provided that the world delivers on rapid and steep emission reductions, and by mid-century, removals are used to balance the small amount of residual emissions, followed by net negative emissions. The governments and corporates are taking on net-zero commitments. The SBTi — which has emerged as the benchmark for ambitious corporate commitments — and the Net Zero Investment Framework only allow removals to be claimed toward net-zero commitments.

Withing the compliance markets, some emissions trading systems have used removals by allowing that type of carbon credits to be used for compliance. The consideration of using trading systems to facilitate the deployment of removals has started and will pick up pace over the coming years.

In the voluntary markets, there is an increasing focus on removals, although removal credits still make up a small fraction of the voluntary market, and a vast majority of those credits don’t offer long-term durability. Meanwhile, the removal credits are getting more and more traction among corporate buyers. Standards and marketplaces like Puro.earth that focus exclusively on removals are experiencing rapid growth. Stakeholders are keen to get their hands on credits that represent high-quality removals.

The convergence of the voluntary and compliance markets will also play out in the context of removals. It will take a little longer for those carbon removal methods where the accounting rules are not yet widely established and no global standards exist. Given the speed and flexibility of the voluntary market standards, they are well placed to contribute and fill the gap. However, the voluntary market can not drive the deployment of removals on the scale needed, and strong policy support will need to emerge from the public sector. The EU’s carbon removal certification is one initiative to keep an eye on. Many other policy tools are being pioneered around the world.

There is already a price difference between removal credits compared to emission reduction credits, the former being more expensive. This trend will continue. The size of the global carbon removal market can grow to $1 trillion when considering the scale of 10Gt at $100 per tonne.

This article is also published on the author's blog. Energy Voices is a democratic space presenting the thoughts and opinions of leading Energy & Sustainability writers, their opinions do not necessarily represent those of illuminem.