Carbon dioxide removal (CDR) market transition risk

· 6 min read

In a previous blog, we highlighted the extent to which the UK carbon removal sector needed to develop and scale by orders of magnitude.

This process of carbon removal - also known as negative emissions - is an essential part of achieving net zero and eventually net negative emissions, both to offset the most persistent remaining emissions and eventually to bring back down the concentration of CO2 in the air to more sustainable levels.

A recent report Delivering the 'Net' in 'Net Zero' [1] by the Coalition for Negative Emissions highlighted the positive steps that are being taken by the UK actors to establish and realise a negative emissions sector along the lines of 3 pillars - as follows (p17 of report):

The report paints a very positivist perspective as to the relationship between the three `pillars’ in how they are mutually reinforcing and `virtuous’. It anticipates that the voluntary sector, which will potentially develop to a $30 to 50B market by 2030, will develop standards that can be incorporated into the regulated sector. The UK government-supported projects will create a supply of negative emissions for investors - up to 5 million tonnes of carbon dioxide per year from the atmosphere by 2030. It aims to grow this amount to 23 million tonnes by 2035. This will perpetuate scale to reduce costs and therefore private sector risk, reducing the dependency on a government-supported market.

At the Carbon Removal Centre, we have been closely engaged with entrepreneurs and activists in the space who have led us to consider the following counter-narratives.

Firstly, the fact that for corporates interest in CDR is not purely a climate play [2]. While climate and sustainability objectives have increasing weight in corporate decision-making, these sit within the broader fiduciary duty of corporate directors to ensure a company's success - especially in providing returns to shareholders. This, therefore, incentivises the motivation to realise climate targets as cheaply as possible.

Secondly, the willingness of corporates to engage in the voluntary sector is based on the balance of risk of not doing so. Should corporates lose confidence in engaging in the sector as a function of civil society advocacy causing brand or reputational damage then the broader willingness of the private sector and as demonstrated in the past for governments to support the sector can also rapidly evaporate [3].

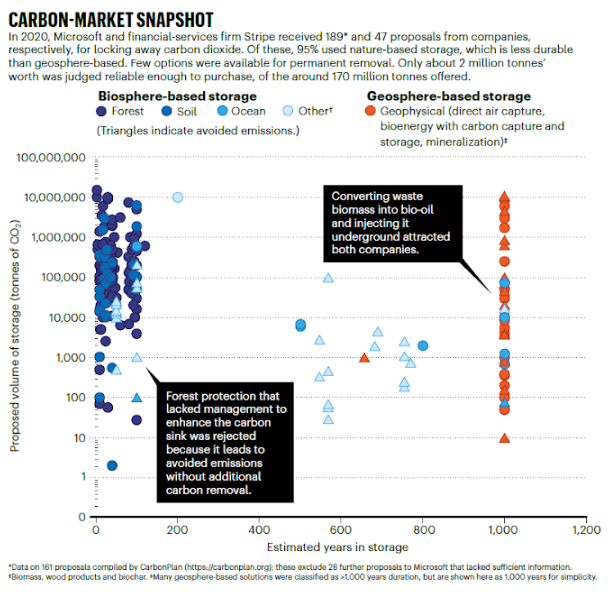

So how do these tensions sit in the nascent negative emissions offset market? Early signs are that the quality of negative emissions offsets in the voluntary sector are highly variable - as per the following observations from two early movers - namely Microsoft and Stripe [4]:

Both Microsoft and Stripe have very strict standards - basing their choices on specific criteria including clarity of carbon accounting, additionality, durability, potential leakage, and other environmental and social considerations. These are unlikely to be the norm for all actors operating in the voluntary market. With such a range of quality and standards - in a market which the private sector is both stimulating supply and calling on demand - all of whom are seeking a return for profit and/or return of value to shareholders. In the absence of oversight and transparent compliance mechanisms - where the credibility of offsets is called into question - will likely result in one of two outcomes.

One where the credibility of the voluntary sector is called out before the establishment of the regulated sector and the other where the credibility of the voluntary sector is called out as a function of the development of the regulated sector. In either case a complete collapse in credibility of the voluntary market with regards to price, legacy offsets and the credible realisation of net zero targets might be a very real outcome. In the case of the former the additional impact will be that the negative emissions off-set market might collapse before it is even regulated and scaled. This could lead to a long delay in government commitments, certainly from funded projects to regulated market i.e. from grants to ETS compliance or similar.

The extent of risks, therefore, loops back to and reinforces the concluding section of the previous blog:

We need to recognise that, unlike the renewable energy transition, substantive and multi-billion corporate engagement in this space is running far ahead of coordinated government action. This means corporate engagement and voluntary standards are setting the shape and tone of the CDR debate. More will be learned by doing than can be worked out in the policy process. This will have negative effects as well as positive ones.

This means there is an urgent need to build an independent and impartial convening safe space which is inclusive which can build trust and knowledge for all actors who are seeking to engage in the negative emissions sector as the sector transitions from a voluntary based to a regulated sector. Based on our research there is a need to:

In short, the UK needs to build a high integrity carbon removal sector from the bottom up - in a way in which all voices are heard, and the results benefit everyone.

This won’t be easy: reality is messy, and the task is daunting. But bringing different actors together around shared societal goals is a crucial first step.

illuminem Voices is a democratic space presenting the thoughts and opinions of leading Energy & Sustainability writers, their opinions do not necessarily represent those of illuminem.

[1] Coalition for Negative Emission 2022 - Delivering the ‘Net’ in Net Zero.

[2] Battersby et al 2022 - The Role of Corporates in Governing Carbon Dioxide Removal: Outlining a Research Agenda.

[3] Department for Transport 2010 - Post-Implementation Review of the Renewable Transport Fuels Obligation: Summary of Responses and Government Response.

[4] Joppa et al., 2021. Microsoft’s million-tonne CO2-removal purchase - lessons for net zero In Nature Vol 597 30 September 2021.

illuminem briefings

Carbon · Environmental Sustainability

illuminem briefings

Carbon Regulations · Public Governance

illuminem briefings

Climate Change · Environmental Sustainability

Politico

Climate Change · Agriculture

UN News

Effects · Climate Change

Financial Times

Carbon Market · Public Governance