· 5 min read

"Net zero" is everywhere. Generally, that’s a good thing, because it is a neat shorthand, and reminder, of the action we urgently need to take to address climate change. Investors have also embraced net zero. And they have a role to play in addressing climate change, so that too is encouraging. However, the way investors embrace net zero is often sub-optimal, for two reasons:

- They seem to think they need to demonstrate that portfolios are net zero on paper, today, which results in mathematical gymnastics using questionable metrics and methodologies, and based on dubious plans and pledges. Whereas in fact what they need to demonstrate is that they understand what needs to happen to get the global economy to net zero in real life, in 2050. And one can ask the rhetorical question: which of these is more important?

- They confuse objectives in committing to net zero investing, resulting in a strange muddle of virtue-signaling, financial-performance-improving, risk-management and world-changing rhetoric that does not result in, but distracts from, the very important supporting role that investors can play: by being active owners, by finding ways to invest in and scale technologies that replace or remove emissions (for example through blended finance) or by supporting governments in developing effective public policy.

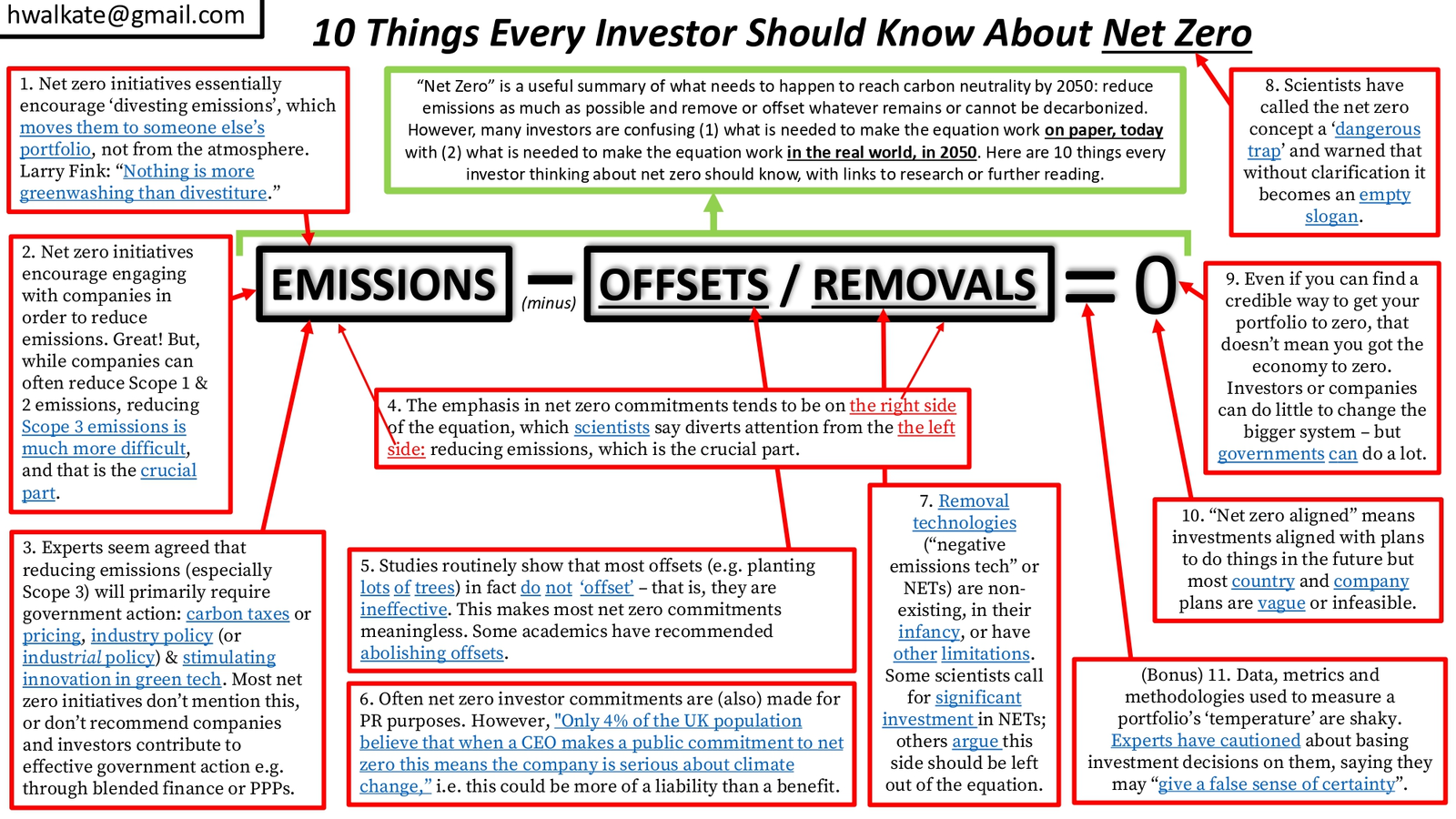

So, in my series of 1-slide PowerPoints that try to make sense of ESG complexity, I tried to capture all the moving parts in this ostensibly simple mathematical equation. In 10 text boxes (and a Bonus Box thrown in) I try to capture the intricacies of net zero investing:

- What happens to emissions when you divest from them? Do they disappear?

- What actually drives down emissions?

- How much can the private sector really contribute to net zero?

- How much should you bank on the ‘right’ side of the equation (offsets and removals) as compared to the 'left' side (emissions)? Are we fooling ourselves when we need to rely on offsets to get us to zero?

- What should you look for when scrutinizing a company’s net zero plans?

- What should you know before making a net zero-investing commitment?

- What are the reputational benefits – or, perhaps, liabilities – in making net zero pledges?

- What more can an investor really do to get the economy to net zero in 2050, in the real world?

As much as possible I’ve backed this up with hyperlinks to papers and articles by (or interviews with) experts, and one podcast series, that provide more of the necessary background and detail.

Each box in this slide is a rabbit-hole you can easily fall into, especially because the links to background publications themselves lead to further publications and background reading. While of course I’ve made this slide and the 11 boxes so that not everyone has to wander around these rabbit-holes, I would encourage you to do a bit of burrowing or tunneling yourself. In doing so, you’ll get a sense for the complexity underlying this seemingly simple equation, and you’ll become familiar with some opinions, facts and concepts that are plainly obvious to many climate experts, engineers, economists and political scientists, but are not part of the popular discourse for whatever reason.

More importantly, I feel that any investor (or company, or country) making commitments linked to net zero, has an obligation to really try to understand which claims they’re making, especially if they are managing other people’s money. In short, by clicking on some of these links and doing some of this further reading, you'll be able to distinguish "Net Zero" from "Not Zero".

And not only will you fulfill your fiduciary duty to the clients who gave you their money to look after, you’ll likely also be making a bigger contribution to addressing climate change than by simply becoming a part of the net zero chorus, which would likely result in net zero becoming – as some climate scientists have warned – an empty slogan.

1. Net zero initiatives essentially encourage ‘divesting emissions’, which moves them to someone else’s portfolio, not from the atmosphere. Larry Fink: “Nothing is more greenwashing than divestiture.”

2. Net zero initiatives encourage engaging with companies in order to reduce emissions. Great! But, while companies can often reduce Scope 1 & 2 emissions, reducing Scope 3 emissions is much more difficult, and that is the crucial part.

3. Experts seem agreed that reducing emissions (especially Scope 3) will primarily require government action: carbon taxes or pricing, industry policy (or industrial policy) & stimulating innovation in green tech. Most net zero initiatives don’t mention this, or don’t recommend companies and investors contribute to effective government action e.g. through blended finance or PPPs.

4. The emphasis in net zero commitments tends to be on the right side of the equation, which scientists say diverts attention from the the left side: reducing emissions, which is the crucial part.

5. Studies routinely show that most offsets (e.g. planting lots of trees) in fact do not ‘offset’– that is, they are ineffective. This makes most net zero commitments meaningless. Some academics have recommended abolishing offsets.

6. Often net zero investor commitments are (also) made for PR purposes. However, "Only 4% of the UK population believe that when a CEO makes a public commitment to net zero this means the company is serious about climate change,”i.e. this could be more of a liability than a benefit.

7. Removal technologies (“negative emissions tech” or NETs) are non-existing, in their infancy, or have other limitations. Some scientists call for significant investment in NETs; others argue this side should be left out of the equation.

8. Scientists have called the net zero concept a ‘dangerous trap’ and warned that without clarification it becomes an empty slogan.

9. Even if you can find a credible way to get your portfolio to zero, that doesn’t mean you got the economy to zero. Investors or companies can do little to change the bigger system –but governments can do a lot.

10. “Net zero aligned” means investments aligned with plans to do things in the future but most country and company plans are vague or infeasible.

(Bonus) 11. Data, metrics and methodologies used to measure a portfolio’s ‘temperature’ are shaky. Experts have cautioned about basing investment decisions on them, saying they may “give a false sense of certainty”.

Energy Voices is a democratic space presenting the thoughts and opinions of leading Energy & Sustainability writers, their opinions do not necessarily represent those of illuminem.