· 4 min read

How will the Russian invasion of Ukraine play out? If the endgame is near impossible to call, the dramatic news overnight narrows the possibilities.

The launch of a ‘special military operation’ against Ukraine closely matches the ‘most likely’ scenario political risk experts at Verisk Maplecroft flagged earlier this week. The events of the February 24, though, also make the main alternative scenario increasingly plausible – a full-scale Russian invasion of Ukraine. At this point, de-escalation via diplomacy looks little more than a faint hope.

Whatever Russia’s ultimate goal, the heightened geopolitical tension is rippling feverishly out into the global economy and markets. We’ll publish specific analysis on the implications for individual sectors imminently. In the meantime, here are our team’s broader thoughts on what the events mean for commodities, energy policy and the energy transition.

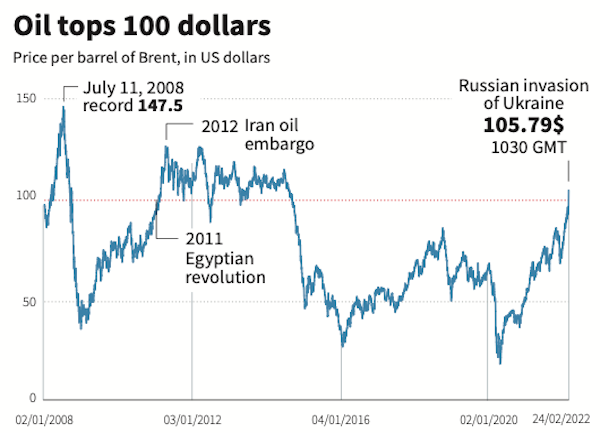

First, Russia has timed its move from a position of strength. With the global economy surging, the world needs all the commodities it can get its hands on, not least Russia’s exports of gas, oil, coal, metals, petrochemicals and fertiliser. Sanctions on exports of these essential commodities are unthinkable – there are no quick fixes should Russia’s supplies be cut off. OPEC has already signalled it won’t ramp up production to lower prices. But in the unlikely event Russian oil supply is cut, we’d expect the organisation to consider supplying extra oil to offset the loss to avoid a global economic crisis.

High commodity prices, inflated by the crisis, are a boon for Russia. Higher export revenues will boost an existing fiscal surplus and swell buoyant financial reserves.

Second, we may be witnessing the beginning of the end of Europe’s umbilical relationship with Russian gas. Europe didn’t get cold feet after the 2014 Crimea invasion. In fact, Russia subsequently proved itself a reliable supplier and imports have actually increased as European domestic production dwindled. Even during this winter, when exports have been lower than market requirements, Russia has still met its contractual obligations. We expect that to continue through this crisis.

The Ukraine invasion appears to be the last straw for the EU – the suspension of certification of Nord Stream 2 is a clear indicator of the future direction of travel. The debate about diversifying gas supply away from Russia will only intensify. New supplies, though, can’t be secured overnight and could lead to higher prices in the medium term. It is a super-bullish signal to LNG developers in the US, Qatar and beyond; as well as pipe options such as Azerbaijan, the East Mediterranean and Norway.

Russian hard commodity exports to Europe and other markets are mostly shipborne, providing more optionality to buyers. These exports include a lot of coal – Russian high-quality exports meet 10% of European coal-fired plant demand. Buyers of all commodities, however, are increasingly having to justify to stakeholders how they source materials. It’s not inconceivable that higher ESG risks stemming from the invasion dampen enthusiasm for Russia’s other big-money earners including aluminium, nickel and other key commodities. ESG concerns could also dent Russia’s goal to become an LNG superpower.

Third, Russia may inadvertently trigger a faster energy transition. Threats to supplies and high prices resulting from the invasion could harden policy and action underway in the EU, UK and elsewhere to move away from fossil fuels.

The EU’s debate around the role of gas in the energy transition was already complicated. Higher gas prices could make coal stickier. They would also make a stronger case for renewables and alternative gases such as bio-methane and green hydrogen, though these will take time to develop at scale. The ambitious target to reduce emissions by 55% by 2030 now looks even more challenging.

And what of Russia’s own transition ambitions? It has plenty of transition metals to supply, notably nickel, cobalt and aluminium as well as bounteous palladium group metals, used mainly in ICE vehicles.

The country also has the potential to be a global low-carbon leader in hydrogen exports (blue H2) and carbon removal. The pipeline infrastructure linked to high-volume emitters in Europe, huge depleted reservoirs for carbon storage and the nation’s vast natural carbon sinks could become giant-scale competitive advantages.

But development and commercialisation will need investment and counterparties. In the current tense geopolitical environment, it’s difficult to imagine there will be much appetite among corporates or investors to commit to such major initiatives and finance them any time soon.

This article is also published by the Edge. Energy Voices is a democratic space presenting the thoughts and opinions of leading Energy & Sustainability writers, their opinions do not necessarily represent those of illuminem.