· 7 min read

In March, the TNFD released a prototype of its long-awaited nature-related risk management and disclosure framework. A guide for financial institutions and corporates to measure their impacts and dependencies on nature, and risks stemming from biodiversity loss. The framework marks the emergence of nature into international financial policy. It is a sign that the right questions are being asked. Most notably, how do we address our systemic failure to price nature’s services within economic models? How do we measure a company, government or person’s impact on nature, knowing that ‘if nature is destroyed, life will cease to exist’? And most importantly, how do we start thinking about an economy that integrates the inescapable fact that human systems are entirely dependent on natural systems?

Conservationists have been battling with these questions for decades, but now the C-suite are also paying attention. While a relief, the business case for protecting nature is fraught with complexities and limitations. TNFD will be in open consultation and development until September 2023 at least; we remain in the early depths of the labyrinth. The five questions that follow measure the temperature of current progress in aligning nature and finance.

Why do companies need to understand nature-related risks?

Anthropocentrism has led us to believe that somehow human systems have outgrown nature. Artificial and processed, everything from our light to our food and clothes points to a profoundly un-natural socioeconomic fabric. But the distance between nature and economy is a fiction mounted in misperception. We are entirely dependent on the services ecosystems house. A silent yet very active sub-structure of our daily lives, nature feeds, clothes, houses us, keeps us healthy and cures us, employs and entertains us. Water provision fed the industrial processes that built the screen I’m typing on. Wetlands protected the screen’s factory from floods, allowing its smooth functioning. Nearby forests made the air breathable for employees; pollination gave those employees lunch, and the energy it needed to grow.

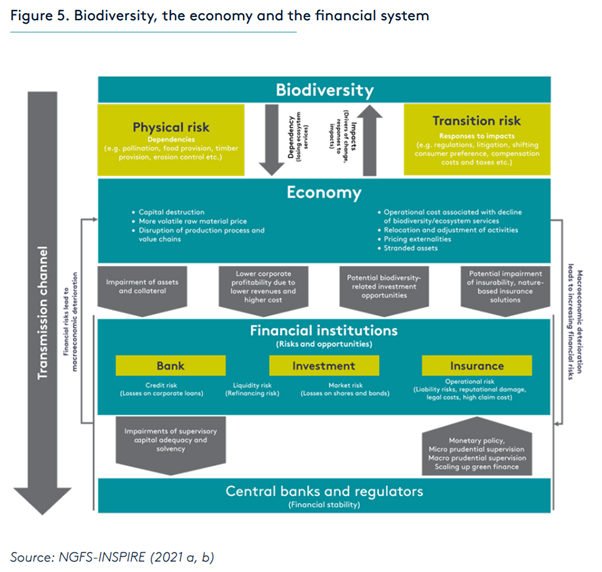

Through their activities, companies have a deteriorating impact on precisely the natural capital assets they require for their activities. Pollution of air, water and soil, fragmentation of ecosystems and habitats for non-human species all reduce the diversity ecosystems need to thrive. That challenges the availability of such assets. Losing natural capital has a very tangible feel in the real economy. It means capital destruction, volatile raw material prices, disrupted value chains, stranded assets…

For example, the Banque de France modelled the ecosystem service dependence of securities held by French financial institutions. 42% are highly to very highly dependent. As those institutions continue to finance agriculture, infrastructure, and urbanisation practices that destroy species tens of thousands of times faster than at any point in history, they expose entire buckets of the global economy to extreme physical risk. Biodiversity and economic stability are mutually deteriorating. Climate change is the self-reinforcing feedback loop that comes on top.

How can businesses account for nature?

Understanding impact is the gateway to correctly pricing nature risk in portfolios and business strategies. To a larger extent than carbon emissions in a value chain, biodiversity impacts are spatially dependent. A mining company operating in both Chile and Australia will use similar industrial processes in both locations, probably resulting in similar emissions. But the species intactness, water and nitrogen levels, and air quality will be different because the company interferes with local organisms and ecosystem-dependent processes in opposed but also innumerable ways. This is why the TNFD’s risk assessment process encourages users to ‘Locate’ their activities as a first step. In this regard, ESG analysts can get ahead by requesting data points from their clients for each asset in their portfolio, including Scope 3.

Measuring the biodiversity impact of those assets is more complex. Two requirements – a quantifiable scope and data availability – are problematic. Metrics must ensure both complexity of analysis and comparability across different spatial and ecological dimensions. As opposed to climate reporting, an aggregate metric may not satisfy these two conditions for biodiversity, precisely because there is no nature equivalent of CO2. What to scope and at what granularity remains unclear. As stated by the Finance for Biodiversity Pledge, biodiversity metrics measure different things to answer different questions.

Spatial diversity makes the measurement approach data-heavy. 70% of investors cite lack of data as a barrier to investing in biodiversity conservation. On the technical side, detailed ground assessments will be key to disclosing impact metrics such as species abundance. Fortunately, interest from the private sector is emerging at a time of rapid technological improvement in geospatial data, AI, and eDNA. On the operational side, insights will be dependent on the combination of ‘asset-level data’ with ‘observational data’ to monitor biodiversity material risks and impacts of portfolios.

Absent international targets for nature conservation, scoping and measurement will remain at the discretion of individual companies and standard-setters. As a result, to cite a nature lead at UNEP FI, ‘the nature disclosure landscape is becoming as diverse as nature itself’. COP15 targets – if separated into biodiversity impact drivers and also broken down into regional drivers – would no doubt lead to a clearer selection of metrics, in turn putting order into the data infrastructure.

Is biodiversity disclosure sufficient?

The climate risk framework TCFD is becoming a disclosure standard in several high-emitting jurisdictions, United States included following recent SEC announcements. Judging from this trajectory and regulators’ growing interest in biodiversity (EU Taxonomy, France Article 29), TNFD developments should crystallise norms over time. The hope is that five years down the line, firms globally report on their nature-related risks. But disclosure is only half the battle. Through harm-reduction strategies, organizations mitigate the deterioration of natural capital assets. But they do not provide a lasting solution to the impacts of exceeded planetary boundaries, nor do they ensure a stable development path that recognises those boundaries. To reach the CBD’s objective of full nature restoration by 2050, organizations must go further, seeking opportunities that benefit both biodiversity and business outcomes.

‘Nature-positive’ is emerging as a narrative for nature restoration. In this scenario, ecosystems and economy are interdependent and offer mutual returns; goods and services, finance, tech, and supply chains all deliver positive outcomes for nature. This requires no less than transforming the most nature-intensive economic systems, but also tackling the indirect drivers of nature loss: trade, consumption patterns, governance mechanisms and values in society. Going nature-positive in critical economic sectors could unlock US$10 trillion of business opportunity and 400 million jobs by 2030.

How do we finance nature-positive?

Private finance has a determinant role to play in placing biodiversity at the heart of economic development. As already stated, the main problem is that nature’s services are not monetized. Financial products, in essence allocation of capital, must return biodiversity benefits. Within the range of products and current gaps, it is useful to differentiate direct and indirect biodiversity benefits.

For direct benefits, the creation of cashflows contributes to enhanced biodiversity, through projects that restore ecosystems. For example, offsetting implies investment into the conservation or restoration of a wetland, forest, seagrass meadow … rewarded by carbon credits and enhanced carbon sequestration. Conversely, indirect benefit concerns support for sustainable business practices. Rather than investing in projects directed at conservation, it is the activities of an organization that results in positive biodiversity impacts. One example could be a large agri-food business implementing regenerative soil management. Here, equity investments in mission-driven enterprises are only one side of the coin; engagement with existing players in the economy, and especially the harder-to-abate sectors, is the other.

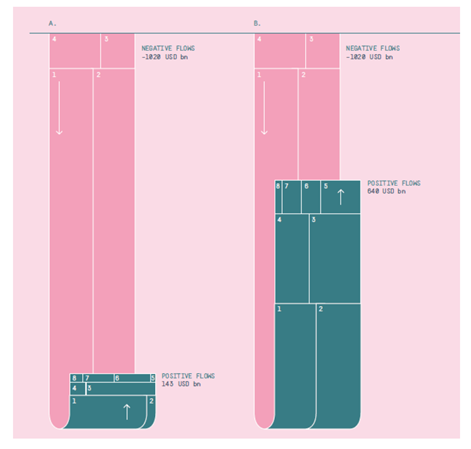

Financial institutions have the capacity to allocate preferences in the real economy, even when engaging with laggards. To stimulate the creation of nature positive markets, both direct and indirect investments in nature must be co-developed. Restoration does not halt biodiversity loss if business as usual carries on at higher levels. To strike a positive balance, the monetization of pressures on nature must be drastically reduced, through investment in durable business practices (see figure below).

What’s the end goal?

As value creation weakens its creators, they have no choice but to adapt their understanding of value itself. ‘Nature-positive’ is not just a business opportunity, a branding tool or a line in a sustainability report. A nature-positive economy will be one that behaves like nature: nature regenerates, and it needs sufficient time and capacity to do so. In fine that means we need to systematically reduce our demand for – pressure on – natural ecosystems. Operationalising that business model is impossible under current consumption rates. However, in the attribution of value to ecosystem services, we have a chance at re-aligning the priorities of human welfare. Environmental services can rapidly become measures of output and wellbeing, both for individuals and corporations. Co-benefits for climate change mitigation and Sustainable Development Goals are numerous. Measuring biodiversity impacts and dependencies in the financial and corporate sector is an essential step to reconsidering the fundamentals.

Future Thought Leaders is a democratic space presenting the thoughts and opinions of rising Energy & Sustainability writers, their opinions do not necessarily represent those of illuminem.