· 11 min read

Two years ago, when the world shut down for an unknown microscopic enemy, I had just started my CO2 removal start-up, Out of the Blue. As I struggled to make sense of what was happening, and what effect it would have on my business, I set out to make an uncertainty model — inspired by an article in the McKinsey Quarterly that regained traction during the pandemic. Now, the world is shaken up by a terrible war in Ukraine. Again, this global issue will have wide-ranging effects on all facets of the economy, among them on the sector I’m still active in, that of CO2 capture and removal.

I didn’t publish this model before because I thought it was too limited, but when I was going through the document recently, I was surprised by how much my model captures the spirit of today.

The price of oil and carbon

There is this simplistic notion that a high price (or tax — later more on that) on CO2 automatically guarantees an increase in energy efficiency programs, and the deployment of CO2 capture and removal technologies. Moreover, it’s tempting to think that if the price of oil is high enough, businesses and individuals alike will have no choice but to use less of it. While both axes are indeed crucial, this independent 2D model is too simplistic. Time to dive in deeper.

Oil price

Let’s start with the y-axis, the oil price.

The oil price is a good measure for the price of energy in general. Only looking at the yearly CO2 emissions makes it clear that whatever the price of oil, gas or coal, the overall demand is only going up (although temporarily, the preferred fossil fuel mix may change). Oil demand in particular has very low demand elasticity: no matter how expensive, there is only that much oil the current economical system can realistically save.

- If you have to take your car to work because there is no bus, you’ll continue to drive to work. The idea that people “switch” to public transport at higher oil prices is absurd, because if there were a real alternative for them, some of them would undoubtedly have chosen it already at some point. And some will never, no matter the alternative.

- There are only so many degrees you can lower your thermostat without insulating your home. Given the exploding real estate prices, property is becoming increasingly inaccessible, which leaves fewer people buying a home (plus: there is less incentive for insulating rental homes), and, for those who still can afford a house, less money to revamp it to the latest energy standards.

- The global supply chains are extremely complex, with goods shipped back and forth across the world. While covid showed this is not an ideal long-term situation, it’s really difficult to untangle this web in the short term. Especially when it comes to essential goods like food or medical supplies.

- The historical oil shocks the world experienced in the past were not a demand problem, they were a supply problem. The world wanted to keep burning oil, there just wasn’t enough on the market. The fact that these episodes weren’t systematic decreases in underlying demand but sudden decreases in supply made them very shocking indeed.

The world relies so heavily on cheap energy, and hence, on cheap oil, that you’re running into some mindblowing facts:

- The higher the price of oil, the worse news it might be for the climate. After all, why would the price be high other than if there were a lot of people who wanted to burn it? Nobody pays 100 USD/barrel for oil (or recently, 300 USD/tonne for coal), to put it on a pile and do nothing with it. Or, put more mildly, the price of oil says little about the volumes of oil being consumed, with huge price variations at slowly varying oil production.

- The lower the oil price, the more breathing room there is for the whole economy, and hence, also for the energy transition. This is what we’re seeing now: purchasing power is a very hot topic at the moment, and the first political reflex is to implement short-term policies to improve the purchasing power. Climate action is not immediately on everyone’s mind in these circumstances.

- To make all the renewable technology, still massive amounts of fossil fuels are used and burned: to mine and refine the necessary minerals, to make the solar panels or build up the wind turbines, to revamp the grid and build charging stations. A lower oil price is good for the industry — all industry, also the decarbonizing one.

Carbon removal in particular needs significant amounts of (carbon-free) energy, not just to build the infrastructure, but also, to run it. The problem is, that is energy is getting scarcer (and hence, more expensive), it is also more expensive to run the CO2 removal process. Moreover, if the general public is already paying more for energy (and all energy-intensive products), there is less support for additional price increases to clean up after the emissions.

In short: a higher oil price says little about the oil use and generally means less breathing room for CO2 removal.

Price on CO2

On to the x-axis, the “price” or tax on CO2.

[Note: For the sake of this article, I’m not going into the intricacies of price versus tax: the mechanisms and implementations of these two are vastly different, even between countries or states. However, what’s important is that large entities (corporates, governments) have to pay a price on CO2.]

Conventional wisdom dictates that the higher the price on CO2, the less CO2 will be emitted. I argue that in a lot of cases, it is actually more appropriate to think the other way around:

The higher the price on CO2, the more CO2 is currently being emitted and the stronger the belief that CO2 emissions are only going to rise.

Why else would you pay such high prices if it wasn’t because you desperately wanted to emit it?

One way of looking at it, is that a lot of the CO2 price mechanisms work with a cap-and-trade system, where companies are allowed to emit a certain amount of CO2 (the ‘cap’, which is lowered over time), and can trade the rest. If all companies were perfectly aligned with the decrease of the cap, then the price of the remaining credits wouldn’t rise (or even become lower). Another way of looking at it, is that in an ideal world, there wouldn’t even be a need for such a mechanism: superfluous CO2 emissions wouldn’t exist, and whatever need for CO2 there was (e.g. kerosine for air travel), could be met with circular technologies.

The high CO2 price is not a direct incentive to increase energy efficiency or to build more carbon capture infrastructure, in fact, it is a sign that too little infrastructure was built in the past. At any point in time, it remains a matter of financial risk: do we as a company spend billions of dollars on a project now, in order to save money several years from now?

This is complicated by the fact that a CO2 tax is often just a purely symbolic accounting trick. Carbon dioxide is not traded like bulk commodities (plastics, grain…) or discrete items (phones, cars…). The majority of the CO2 traded is “CO2 not emitted”: big polluters paying slightly-less-big polluters to emit CO2 in their stead.

On top of that, there is a myriad of fossil fuel subsidies, which are effectively lowering the carbon price (You could also argue that the subsidies are lowering the net oil price, but given that the oil question is supply-driven, I think the subtraction is better done from the carbon price). Anyway:

It’s better to talk about the effective or net CO2 price.

Here’s why, using the example of the European Union’s ETS market (the largest CO2 market in the world)

- As of this writing, the price is hovering around 80 EUR/tonnes.

- Only 40% of EU CO2 emissions are counted in this market, which translates to 1.6Gtonne. That mean it is a market of 128GEUR/year.

- However, in the EU alone, there are 50 GEUR of fossil fuel subsidies yearly.

- And, it turns out that in the “EU green recovery”, over 150 billion dollar was spent supporting fossil fuels.

While these numbers are anecdotal at best, and definitely need to be refined, it is clear that the CO2 price is far from the price paid at ETS trading, and it could be argued that the effective or net price of CO2 is much lower than the current price.

My mental model

Bringing it all together, the following picture appears:

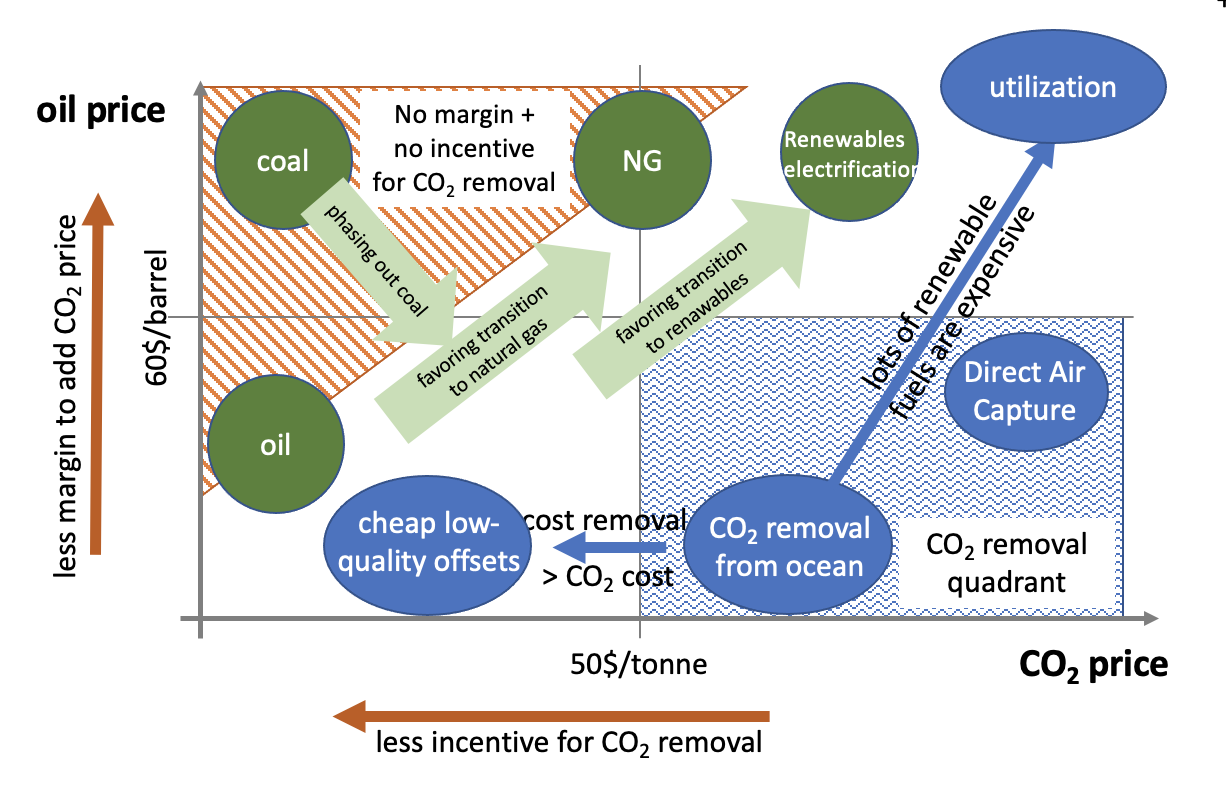

- On upper left, at high oil prices and low CO2 prices, there is both little economical breathing room nor financial incentive to do CO2 capture or removal. The most that can happen here, is an optimization of the fossil fuel mix: at very high oil prices, one can expect even coal to be used, which will phase out with lower oil prices and CO2 price/tax incentives. Adding a price on CO2, policy will move natural gas (NG) in the mix. And the combination of high oil prices and increasing the CO2 price speeds up the transition to renewables and electrification, both in personal transport and in shipping.

- For CO2 removal to become viable, low energy prices, and therefore, low oil prices are needed. At low CO2 prices (in the left bottom corner), the weak incentive means that the cost of any high-quality CO2 removal is higher than the price you could charge for them. Cheaper, but lower quality offsets are possible though (think: 2 EUR to offset a transatlantic flight)

- The sweet spot for CO2 removal technologies lies at high CO2 prices and low energy/oil prices — this is the CO2 removal quadrant in the lower right. In there, two potential approaches: Direct Air Capture, and Indirect Ocean Capture. As I’ve written earlier, I’m convinced that CO2 removal from the ocean is (energetically) cheaper than removing it from the air (Direct Air Capture). That means it needs less energy, and is hence less susceptive to high oil prices. Moreover, it offers potential for local synergies, that can also be monetized.

- Finally, in the case of high CO2 prices combined with high oil prices (and local access to excess renewable energy, like in Iceland or Québec), it makes more and more sense to use the captured CO2 to utilize it in certain applications, like synthetic fuels for aviation, or building materials.

Historical evolution in this field.

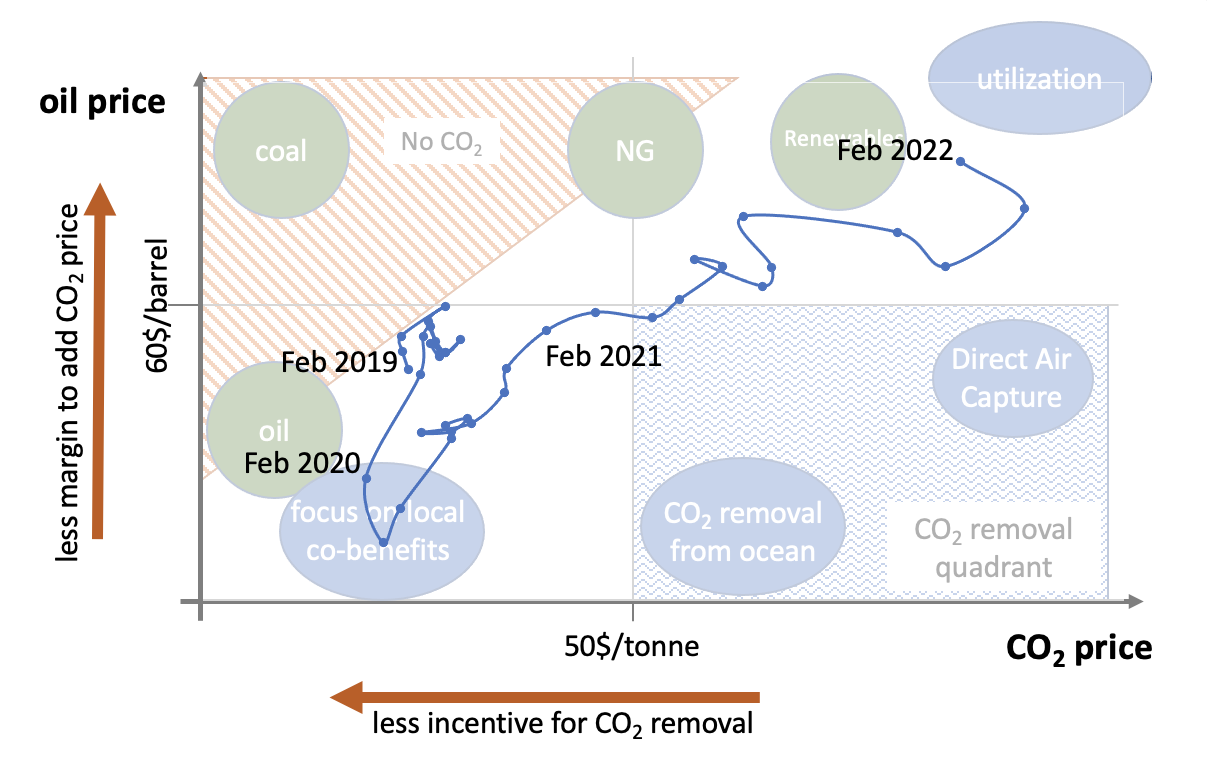

Finally, let’s see how the position in this field evolved in the last 3 years. To do this, I’ve take the monthly average oil price and ETS CO2 price. The European Trading Scheme is the largest public market of CO2 emissions.

The year before the COVID-19 pandemic, we were in a situation where oil was cheap, and the CO2 price was too low to do much about CO2. However, there certainly was a phase-out of coal, and a move towards natural gas happening.

Then the pandemic made the oil price collapse (do you remember the negative oil prices, where oil storage was getting saturated?). Initially, the ETS price went down as well: there was fear for a recession, projections were that the economy would slow down. However, despite an initial dip in the ETS price, the price went up (with the cautionary statement that this may have been partly canceled out by the massive economic stimuli).

This was the moment for CO2 action though: there was an incentive to start doing something about the CO2 emissions. However, very quickly, energy prices soared as well, which was exacerbated by the war in Ukraine. Just browsing the news, it is clear that the climate is even less a priority then before.

Today, energy is scarce. By cutting out Russian oil and gas, without a reduction in demand, there is only that much energy available, making energy prices soar. Moreover, for any CO2 removal technology you need renewable energy to make sure the process is on net removing CO2.

So we are in a moment, where it makes sense for the CO2 capture and removal industry to look at CO2 utilization strategies. And of course, it makes a lot of sense to switch as much of the fossil fuel infrastructure towards renewables — not just from a climate, or CO2 management point-of-view, but also out of energy security, raw material independence and geopolitical considerations.

Conclusion

Only looking at the CO2 price is too limited to explain incentives for carbon capture and removal, and a more holistic approach is needed. In particular, the oil price is a crucial parameter in understanding the business case. Massive amounts of cheap, low-carbon energy are needed to build the CCS and CDR infrastructure, and to run it in an effective and carbon-negative way.

This is an important consideration for policy makers and companies alike: to solve both the energy and the CO2 question with well-aligned incentives, and avoid counteracting them with well-meant but ill-reasoned subsidies. Finally, one can wonder if leaving this Herculean and decisive task solely to the “free” market will provide the desired results in time.

In any case: what a time to be alive, and be working in the CO2 industry!

This article is also published on the author's blog. Energy Voices is a democratic space presenting the thoughts and opinions of leading Energy & Sustainability writers, their opinions do not necessarily represent those of illuminem.