Climate Policy – It’s Not About the Science

· 11 min read

Politicians have politicised the science and given us no choice in the matter. Our only choice at this point is to accept their false framing or to fight against it. (Emphasis added)

Katherine Hayhoe

This is the third in a casual series of discussions on today’s politics and what it means for US climate policy. The new series flows from a conversation I had with a colleague in preparation for a podcast in which she would be interviewing me.

I answered nearly every question she asked in the run-through by talking about politics. I could tell she was frustrated with the direction of the conversation. Finally, she raised her hand and said—“STOP! The group wants to hear how US policymakers are accommodating the latest IPCC report and the most recent developments in climate science.”

“These days,” I said, “US climate policy is not about the science. It is all about politics. Facts have been shown to have no place in the debate. Lies are in; truths are out—even when the truth is on tape or can be otherwise documented.”

Last year [2020], we had a rigged election, and the proof is all over the place. We have a lot of proof, and they know it’s proof. They always talk about the Big Lie — they’re the Big Lie.

Donald J. Trump/January 15, 2022

Trump and allies like Michael J. Lindell, Rudi Giuliani, and the Kraken keeper Sidney Powell, have failed to convince even one out of the 60 courts in which their claim—that the 2020 presidential election was stolen out from under the feet of the former president—was considered.

The over-arching challenge to the climate community isn’t to develop and gather more proof of Earth’s warming. For as long as the climate activist community fails to convince enough Republicans and Independents to support the myriad policies needed to make a relatively rapid and just transition to a low-carbon economy, activists and their data points will only further convince themselves.

I recognize that the last sentence can be a bit puzzling and may even appear harsh. After all, the statement is in opposition to the conclusions of dozens of voter surveys—current and past—on environmental protection and clean energy.

You would have to dig deep to have any chance of finding an opinion survey in which clean energy, e.g., solar and wind, is thought undesirable by a majority of the respondents. However, the reality is quite different. A substantial segment of the population sees neither the truth, urgency, nor the need to do anything about climate change.

Today, we have reliable renewable energy technologies that are up and running. For the past several years, solar and wind have been the sources of choice for utility-scale electric generators when adding new power supplies.

Big tech companies purchased a record 31.1 GW of clean energy in 2021. In 2022, European industries are rushing to add on-site solar panels to offset the rise in prices and reductions in oil and gas supplies brought on by Putin’s war on Ukraine.

Utilities and corporations are not the only ones showing interest and confidence in solar and wind technologies. The US Department of Defense (DOD) has invested hundreds of millions of dollars in developing “battle-ready” renewable energy systems.

Taking defense installations off the grid means they’ll be harder to find and hack. Mobile power sources, e.g., flexible photovoltaic panels that don’t require long supply lines or hauling heavy equipment, increase battlefield readiness.

The DOD is hardly alone in its pursuit of wearable power supplies. The UK Ministry of Defense is developing infantry clothing with solar power technology that produces energy from sunlight during the daytime and switches to thermo-electric devices to capture the soldier’s body heat and convert it into energy whenever the sun isn’t around.

Putin’s war gives new meaning to the phrase “national security.” As we’re seeing in Ukraine, oil and gas have become weapons of war. Can any nation really be secure when someone else controls its “blood” supply? Experience suggests “not.”

The fragility of friendships between nations requires the US to reflect on its addiction to oil and not just about the price per gallon. The cost of gasoline is not the same as its price. Price is what consumers pay. Cost is what society pays [over time].

As you would imagine, assigning costs and valuing benefits can be tricky.

What’s the actual cost of a kilowatt-hour or a gallon of gas? Should the health effects of coal on miners and populations close to coal-burning power plants be factored into the cost equation?

What about Putin’s war? There are the tens of millions of dollars for humanitarian aid and the billions of dollars in armaments for the Ukraine military to consider. But what of the food insecurity of Tunisia and other Middle Eastern and African countries that depend upon Ukraine for their grains?

The cost of something can’t always be monetized, nor is it always recognizable until it’s too late. A cancer may be in the body without showing any signs. Then one day, the patient sees a doctor because of some pain. The tests show where the cancer was initially hiding and how it has metastasized throughout the whole body.

Harms can be in plain sight but not understood for what they are. Two hundred thousand soldiers are at a nation’s door. But no one behind the door believes any sane person would wage war, so they go about their daily business paying little mind to the threat in plain view.

Then the first missiles are launched, and a war of attrition begins. Climate change is a lot like this. We see rising oceans and lowering potable water levels as a normal phenomenon. There are mountains of snow one year and none the next. Isn’t this normal? Doesn’t the weather always change?

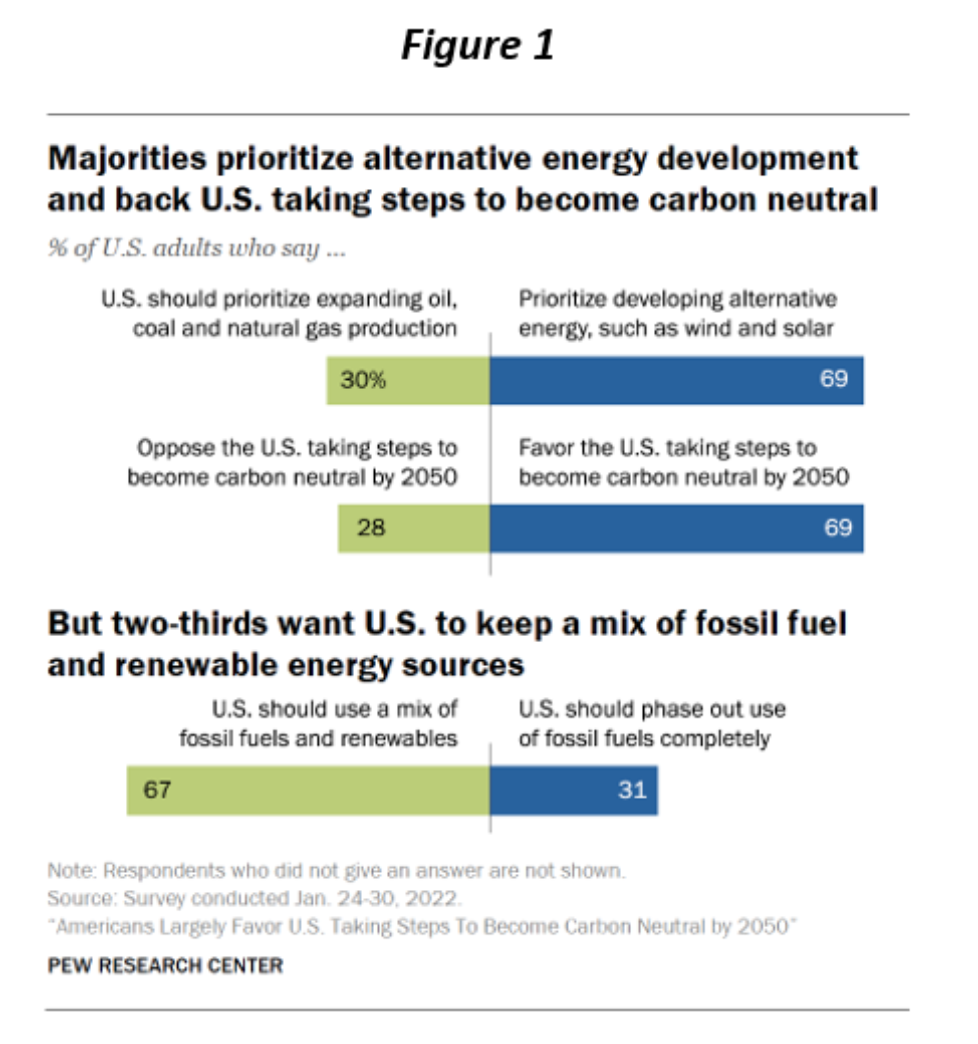

What’s different? Why should we be more concerned about this year’s snowfall numbers and increased coal burning in response to Putin’s war than a decade ago? Science is telling us why, but two-thirds of Americans think “the United States should use a mix of fossil fuels and renewables in the future, rather than phase out fossil fuels completely.”

About 28 percent — including more than half of Republicans — oppose the US

taking steps toward becoming carbon neutral.

A Pew survey suggests support for renewable resources is flagging among Republicans—an area seen as one of the few climate-related places Democrats and Republicans could collaborate.

Splits between the parties are also happening within them. Progressive and establishment Democrats are experiencing their own battles. Although generally in favor of doing something to combat climate change, establishment and progressive Democrats can’t seem to agree on what that something is.

The Democratic establishment blames the party’s poor showing in the 2020 congressional elections at the feet of their progressive colleagues. They blame progressive phraseology like “Defund the Police” for the near loss of the control of Congress.

The most forceful voice raised against such phraseologies is Representative James Clyburn (D-SC). The Congressman is Black, a recognized civil rights leader, and considered responsible for Biden’s remarkable emergence as the Democratic candidate [1].

Clyburn has not been shy about throwing his weight against progressive messaging, including the Green New Deal. He’s likened such phrases as “Defund the Police” to civil rights efforts in the 1960s when public support for the movement’s objectives was eroded by radical messaging. The message? Burn baby burn!

Representative Clyburn is hardly the only voice against progressive catch-phrases. Basically, every Democrat running for Congress in every purple state and district feels the way Clyburn does. Unsurprisingly Representative Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (AOC) does not.

A few days following the 2020 elections, AOC sharply rejected the notion that progressive messaging around the summer’s anti-racism protests and more radical policies like the Green New Deal had led to the party’s loss of congressional seats. Things have changed dramatically since that interview.

The battle between establishment and progressive Democrats is not only in Congress. It’s now in the primaries, as progressives are mounting challenges to incumbent Democrats.

Jessica Cisneros (D-TX) is again battling Henry Cuellar (D-TX) in Texas. She’s receiving support for her quest from leading progressives, including Bernie Sanders (I-VT) and Elizabeth Warren (D-MA,) and Representative Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (D-NY).

Cuellar has represented the Texas 28th congressional district since 2005 and has the support of Speaker Pelosi and other Democratic congressional leaders. He is the second-biggest Democratic recipient of oil and gas monies, while Cisneros has signed a No Fossil Fuel Money Pledge.

President Biden’s grim job approval ratings (41 percent), the historic inflationary numbers, abortion, and Putin’s war are contributing to the uphill battle of the 2022 midterm elections. Although a majority of voters don’t blame Biden for higher gas prices, they appear willing to blame him for everything else that’s gone wrong or might go wrong.

Although majorities say alternate energy development should be a priority and that the US should become carbon neutral by 2050, two-thirds want to keep fossil fuels in the mix.

Looming large on the horizon are the 2022 midterm elections. Electioneering will mean a long summer recess. It also means that any legislation not passed by Congress by Memorial Day (May 30th) or the early days of June will not get acted on until the fall.

The renewable industry hopes to have the current production and investment tax credits extended. It’s something Senator Manchin has said he’d be willing to support—but not without getting something in return. What that would be isn’t difficult to divine.

Manchin has begun informal talks with a bipartisan group of senators to discuss what they might all be able to agree on by way of energy/climate legislation. Manchin is proposing to package an “all of the above” array of supports— including for the fossil fuel industry.

If a deal is reached, it’s likely to be because of the same group of senators who were able to put together and pass the stand-alone infrastructure bill. The group’s Republicans would include Murkowski (R-AK), Collins (R-ME), and Romney (R-UT).

Manchin has intimated he would be prepared to craft a stand-alone energy bill outside the budget reconciliation package. However, he would need ten Republican senators to join with the Democrats.

As one would imagine, much of the climate community is not pleased by the deal that “might” be struck. The renewables industry, including the auto industry, won’t say “No” to having their credits extended. If they’re to be as part of a package that includes fossil fuel supports, then so be it.

The Sunrise Movement, Evergreen Action, and other progressive organizations are opposed to any support for fossil fuels. Although unlikely to stop another Manchin negotiated “all of the above” energy and environment bill, the tension between the establishment and progressive wings of the Democratic Party keeps tightening and, at some point, may rend its apart.

The solar industry, in particular, is in an uncomfortable position. The US industry is facing supply chain problems and experiencing inflationary pressures like everyone else who gets things from China. The solar industry, however, has a more immediate concern.

The Biden administration is investigating whether solar panels and cells imported from Malaysia, Vietnam, Thailand, and Cambodia actually come from China. If the Department of Commerce finds that the four countries are being used to circumvent the China tariffs, panels from these companies would be subject to tariffs ranging from 50 to 250 percent.

A finding of “made in China” and the level of tariffs on incoming photovoltaic panels would be devastating to the industry, as 80 percent of all crystalline silicon come from the four Asian nations. And 83 percent of US solar companies use them [2].

The promise of the Biden presidency for US climate policy may never be realized. I don’t envy the President his job. What he’s had to contend with—a pandemic, runaway inflation, war in Europe, responding to a rising tide of refugees trying to enter the country legally or not, droughts, floods, forest fires, other natural and climate-related disasters, a highly partisan Congress and electorate, and a hostile minority party led by Donald Trump—would make Job weep.

Biden asked to be president and convinced enough of the nation that he was more man-for-the-job than Trump. He just isn’t doing it very well, at least when it comes to his domestic agenda—the centerpiece of which was his proposed once-in-a-generation investment in a just transition to a low-carbon environment and economy.

The near-term future of US climate policy will be determined by Washington politics, not by quoting another finding of the IPCC or offering up the latest economic study. If that sounds harsh, it is.

In the near term, any legislative action by Congress and President Biden in support of clean energy—possibly the broader environment—will likely be brokered by Joe Manchin and be all about the politics.

I’ll be addressing these topics and others in the next article in the series, in which I’ll also try to answer the question –

How do you convince someone—whether policymaker or regular Joe—of the facts when fancy has been normalized, even demanded, by presidents?

From the next installment –

The most powerful Joe in the nation’s Capital City has some deciding to do. No, no, not that Joe. Although he, too, has some decisions to make.

Energy Voices is a democratic space presenting the thoughts and opinions of leading Energy & Sustainability writers, their opinions do not necessarily represent those of illuminem.

[1] Clyburn and John Lewis were founders of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC).

[2] A group of 16 Republican and Democratic senators have sent a letter to the President asking him to speed up the investigation, and outlining for him the economic impacts of the tariffs would be.

Michael Wright

Agriculture · Environmental Sustainability

Charlene Norman

Sustainable Business · Sustainable Finance

illuminem briefings

Climate Change · Ethical Governance

The Guardian

Pollution · Nature

World Economic Forum

Carbon Removal · Sustainable Investment

El Pais

Climate Change · Effects